A piece in ChinaDailyUSA wittily entitled Rice of Ages prompted some sleuthing. The gist of the piece is that there’s a traditional rice landrace in a small corner of Jiangxi province…

A kind of rice that locals call Wuyuanzao has been grown in Wannian county in northeastern Jiangxi for more than 12,000 years.

The age-old rice variety is precious in the eyes of agriculture professionals. But Wu-yuanzao, commonly known today as Wannian rice, can only thrive in the county’s Heqiao and Longgang villages, which are near Poyang Lake.

…which is pretty special not just because it (or something that became it, or something like it, or something with the same name as it, or…) has been there for ages…

It can reach 1.8 meters while ordinary rice grows less than 1 meter high.

Also, there is no need for pesticides or chemical fertilizers since this “heirloom” rice variety has proven resistant to insects and over centuries has adapted to low soil fertility.

Wannian rice also delivers richer nutrition than many other varieties, since it contains high levels of protein and vitamin B.

Its growing period is 160 to 175 days — much longer than the 130-day period for ordinary rice varieties…

…but unfortunately it is no longer being grown as in the past…

“Lower output and huge labor input — because of traditional farming methods that the rice has — led more young people to abandon the self-sufficient lifestyles of their forefathers and go to work in cities,” Zhan says.

The ancient rice produces 3 tons per hectare, compared to the average 9 tons per hectare for the ordinary rice varieties in one season, local figures show…

“But now I am still quite worried that no one will be willing to plant the ancient rice in the future. Then the rice variety is very likely to vanish,” Zhan says.

…and therefore it must be protected…

The rice in Wannian county and its affiliated culture system was listed as an FAO global protection project in 2010…

Local officials have raised the purchasing price for Wannian rice to three times the price of ordinary rice, to encourage farmers to keep planting it.

…although the jury is out on whether that’s working.

Today, even in Wannian county, it is still rare to see the precious ancient rice outside the 20-hectare protected area. The cultivation area was more than 3,000 hectares as recently as 1950, according to local agricultural authorities.

So, some more detail. The “FAO global protection project” alluded to is the Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS). Wannian Traditional Rice Culture is indeed one of the systems protected under this scheme, and very nice it looks too. ((Sidebar: Why doesn’t GIAHS make its photos on Flickr more easily accessible?)) The accompanying documentation gives some more detail on that famous Wuyuanzao rice variety, which remember the original article also tells us is “commonly known today as Wannian rice.”

This kind of rice formerly called “Wuyuanzao” and commonly known as “Manggu”, has been cultivated in Heqiao Village since the North and South Dynasty. Its morphology is similar with wild rice and its ancestor is Dongxiang wild rice which is nearby Wannian County.

So that’s three names now, for allegedly the same thing. Well, not quite, as the same document also provides two additional synonyms: the traditional variety name Gong Gu and, more formally, “Oryza sativa L. spp. hsien Ting.” Confused? I certainly was.

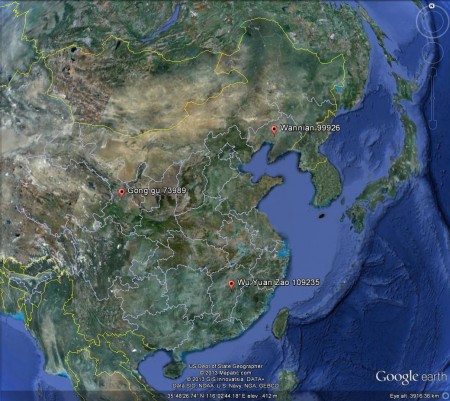

But not as much as I was to become. For on consultation with our friends at Los Baños and with Genesys, it turns out that there is a rice called Wu Yuan Zao from Jiangxi in the IRRI genebank (Acc. No. 109235). It is shorter (culm length at reproduction 71-90 cm) and not as slow growing (days to full maturity 105) as advertised, but that could be an environmental effect, of course. However, there is also a quite different variety (even shorter, for a start) called Wannian (99926), collected miles away from the place of that name. And a variety called Manggung (71568), but from Malaysia. And a variety called Gong gu (or maybe Duan mang; 73989) collected in yet another different place. There are also numerous names which include the words “hsien” and “ting”, but none of them together.

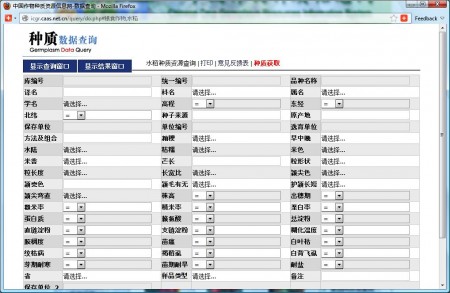

Bottom line: I’d like to see the rice landrace(s) grown in that GIAHS in Jiangxi conserved in a genebank. You know, just in case tripling its price by fiat is not enough. Because I’m not convinced it’s in the IRRI genebank already. And until CAAS translates its database, or a Mandarin speaker out there helps me out, I’m not likely to to find out whether it’s in the Chinese national genebank either, under whatever name.