Mark Easton, the BBC’s home editor, starts a blog post today with this quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson as an introduction to making the point that the protected area of Wicken Fen in Lincolnshire is…

…the product of complex interaction between plants, birds and animals. And fundamental to its existence were the apparently destructive activities of one animal in particular: man.

Well, that could be said of a lot of landscapes around the world. Even, possibly, as is increasingly argued, places like the Amazon, which until recently was generally regarded as nature in its most pristine state.

But to go back to Wicken Fen, which, incidentally, I remember very fondly, having done a certain amount of fieldwork there as an undergraduate. It seems “the [UK] government, anxious to protect another fragile habitat, the peat bog, wants 90% of composts and soil improvers to be peat-free by next year.” So peat digging was banned at Wicken Fen. Good, you say? Well, not so much. This change in a practice that has been going on for centuries has contributed to the local extinction of the rare fen orchid. And not only that, the fen violet too, probably:

The rural culture – which had cut the sedge for roofing and animal bedding – disappeared and the fen violet along with it. Its seeds may still survive in the peaty soil and occasionally a rare plant will push through the surface if the land has been disturbed, but the violet has not been seen at Wicken for more than a decade.

And the swallowtail butterfly and Montagu’s harrier as well, due to past changes in management practices.

So what to do. As Mark Easton says, nowadays “conservationists ape the principles of the ancient harvesters to protect what is left of the fen.” But not all agree. “Instead of trying to counteract nature, man should work with it.”

This is a much less predictable approach to conservation but, it seems to me, it is a philosophy more in tune with an acceptance that man is not god. We are part of nature too.

Fair enough, but what if you are managing a protected area specifically for a particular species of value? Say an important crop wild relative. I can imagine a situation where you might want to be a bit more intensive in your intervention, and a bit more predictable. Which is one of the reasons why I don’t think that “conventional” protected areas such as your average national park will ever be much use for CWR conservation, except by chance.

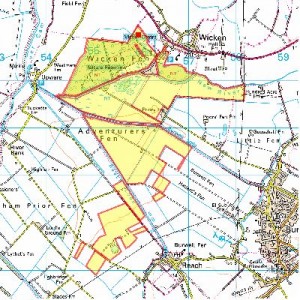

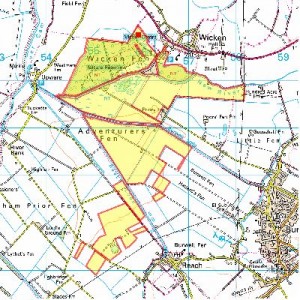

Incidentally, there’s a couple of CWRs at Wicken Fen, according to the great mapping facility on its website. Here’s where you can find Asparagus officinalis, for example: it’s that red square right at the top.