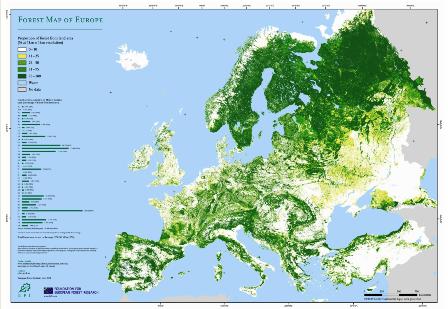

As usual, it never rains but it pours. Within a few minutes yesterday I was pointed by different sources towards the Forest Map of Europe, Tree species maps for European forests, the Condition of Forests in Europe report, a review of Dynamic Conservation of Forest Genetic Resources in 33 European Countries, and a paper on the Uses of tree saps in northern and eastern parts of Europe. Thinking that there might be something in the air, I did a quick search of my RSS feed, and found another very recent review, Translating conservation genetics into management: Pan-European minimum requirements for dynamic conservation units of forest tree genetic diversity. What’s got into the European forest conservation community? Has ash dieback got them all running scared? And is someone going to put all European forest-related maps together somewhere (eg, Eye on Earth)?

As usual, it never rains but it pours. Within a few minutes yesterday I was pointed by different sources towards the Forest Map of Europe, Tree species maps for European forests, the Condition of Forests in Europe report, a review of Dynamic Conservation of Forest Genetic Resources in 33 European Countries, and a paper on the Uses of tree saps in northern and eastern parts of Europe. Thinking that there might be something in the air, I did a quick search of my RSS feed, and found another very recent review, Translating conservation genetics into management: Pan-European minimum requirements for dynamic conservation units of forest tree genetic diversity. What’s got into the European forest conservation community? Has ash dieback got them all running scared? And is someone going to put all European forest-related maps together somewhere (eg, Eye on Earth)?

Describing Nordic apples

Oh dear, here’s another agrobiodiversity documentation project that we’ve missed. Over the past few years NordGen has been supporting the Norwegian Genetic Resource Centre in describing apple varieties. That much I can make out in the Google translation of the original Norwegian web page describing the project. But not much more than that. For some reason, the translation is much worse than is usually the case. Maybe it’s the technical language. Anyway, I don’t think there are any data online yet, but when they are, they may or may not be integrated into the database of Danish apple varieties that NordGen manages, complete with handy key. Which is also in English.

India gets its PGR data online

I’m not entirely sure how we missed that data on India’s enormous germplasm collection is now online. While this is welcome, I think it’s fair to say that NBPGR’s PGR Portal still needs some work in terms of user experience. It took me a while to figure out, for example, that if you type a letter under “Crop/Plant Name,” in Passport or in Characterization and Evaluation Search, you get a list of crops beginning with that letter, which you can then choose from. 1 Once you do that you get a list of taxonomic names to choose from, but you can only select one at a time to do your search. And why no rice data at all? There is a nice way of looking at the distribution of different character states for each characterization and evaluation descriptor, but no mapping facility. And you can’t use the portal to order germplasm. To do that you have to fill in a form, which makes no mention of the International Treaty on PGRFA or its SMTA, and email it in. And there are some funny restrictions on use: “All users can search and see the desired information. only registered users can copy and download.” But I couldn’t find a way to register. So, good to see, though clearly a work in progress. Will follow its development closely, and hope to see it link up with Genesys in due course, joining the CGIAR, European and US genebanks.

I’m not entirely sure how we missed that data on India’s enormous germplasm collection is now online. While this is welcome, I think it’s fair to say that NBPGR’s PGR Portal still needs some work in terms of user experience. It took me a while to figure out, for example, that if you type a letter under “Crop/Plant Name,” in Passport or in Characterization and Evaluation Search, you get a list of crops beginning with that letter, which you can then choose from. 1 Once you do that you get a list of taxonomic names to choose from, but you can only select one at a time to do your search. And why no rice data at all? There is a nice way of looking at the distribution of different character states for each characterization and evaluation descriptor, but no mapping facility. And you can’t use the portal to order germplasm. To do that you have to fill in a form, which makes no mention of the International Treaty on PGRFA or its SMTA, and email it in. And there are some funny restrictions on use: “All users can search and see the desired information. only registered users can copy and download.” But I couldn’t find a way to register. So, good to see, though clearly a work in progress. Will follow its development closely, and hope to see it link up with Genesys in due course, joining the CGIAR, European and US genebanks.

Brainfood: Climate in Cameroon, Payments for Conservation, Finger Millet, GWAS, Populus genome, miRNA, C4, Cadastres, Orange maize, Raised beds, Contingent valuation, Wild edibles, Sorghum genomics, Brazilian PGR, Citrus genomics

- Climate and Food Production: Understanding Vulnerability from Past Trends in Africa’s Sudan-Sahel. Investment in smallholder farmers can reduce vulnerability, it says here.

- An evaluation of the effectiveness of a direct payment for biodiversity conservation: The Bird Nest Protection Program in the Northern Plains of Cambodia. It works, if you get it right; now can we see some more for agricultural biodiversity?

- Finger millet: the contribution of vernacular names towards its prehistory. You wouldn’t believe how many different names there are, or how they illuminate its spread.

- Genome-Wide Association Studies. How to do them. You need a platform with that?

- Revisiting the sequencing of the first tree genome: Populus trichocarpa. Why to do them.

- Exogenous plant MIR168a specifically targets mammalian LDLRAP1: evidence of cross-kingdom regulation by microRNA. “…exogenous plant miRNAs in food can regulate the expression of target genes in mammals.” Nuff said. We just don’t understand how this regulation business works, do we.

- Anatomical enablers and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis in grasses. It’s the size of the vascular bundle sheath, stupid!

- Land administration for food security: A research synthesis. Administration meaning registration, basically. Can be good for smallholders, via securing tenure, at least in theory. Governments like it for other reasons, of course. However you slice it, though, the GIS jockeys need to get out more.

- Genetic Analysis of Visually Scored Orange Kernel Color in Maize. It’s better than yellow.

- Comment on “Ecological engineers ahead of their time: The functioning of pre-Columbian raised-field agriculture and its potential contributions to sustainability today” by Dephine Renard et al. Back to the future. Not.

- Environmental stratifications as the basis for national, European and global ecological monitoring. Bet it wouldn’t take much to apply it to agroecosystems for agrobiodiversity monitoring.

- Use of Contingent Valuation to Assess Farmer Preference for On-farm Conservation of Minor Millets: Case from South India. Fancy maths suggests farmers willing to receive money to grow crops.

- Wild food plant use in 21st century Europe: the disappearance of old traditions and the search for new cuisines involving wild edibles. The future is Noma.

- Population genomic and genome-wide association studies of agroclimatic traits in sorghum. Structuring by morphological race, and geography within races. Domestication genes confirmed. Promise of food for all held out.

- Response of Sorghum to Abiotic Stresses: A Review. Ok, it could be kinda bad, but now we have the above, don’t we.

- Genetic resources: the basis for sustainable and competitive plant breeding. In Brazil, that is.

- A nuclear phylogenetic analysis: SNPs, indels and SSRs deliver new insights into the relationships in the ‘true citrus fruit trees’ group (Citrinae, Rutaceae) and the origin of cultivated species. SNPs better than SSRs in telling taxa apart. Results consistent with taxonomic subdivisions and geographic origin of taxa. Some biochemical pathway and salt resistance genes showing positive selection. No doubt this will soon lead to tasty, nutritious varieties that can grow on beaches.

Nibbles: Mashua info, Veggies programme, Rice research, Genomes!, Indian malnutrition, Forest map, British agrobiodiversity hero, GMO “debate”, Lactose tolerance, Beer

- New Year Resolution No. 1: Take the mashua survey.

- New Year Resolution No. 2: Give the Food Programme a break, it can be not bad. As in the case of the recent episode featuring Irish Seed Savers and the only uniquely British veg.

- New Year Resolution No. 3: Learn to appreciate hour-plus talks by CG Centre DGs. And other publicity stunts…

- New Year Resolution No. 4: Give a damn about the next genome. Well, actually…

- New Year Resolution No. 5: Try to understand what people think may be going on with malnutrition in India. If anything.

- New Year Resolution No. 6: Marvel at new maps without fretting about how difficult to use they may be.

- New Year Resolution No. 7: Do not snigger at the British honours system.

- New Year Resolution No. 8: Disengage from the whole are-GMOs-good-or-bad? thing. It’s the wrong question, and nobody is listening anyhow.

- New Year Resolution No. 9: Ignore the next lactose tolerance evolution story. They’re all the same.

- New Year Resolution No. 10: Stop obsessing about beer. But not yet. No, not yet.

- Happy 2013!