- Learn about iron beans from a HarvestPlus video, maybe.

- Learn about the tomato in Ghana, more than you might need to know if you read all the reports.

- Learn how Andy Jarvis spoke truth to ex-power, about fruit data gathering project prospects.

- Learn how the Africa College, based at Leeds University in the UK, is working on a range of agricultural problems.

How would you promote agricultural biodiversity?

Here’s the scenario: the civic authorities have decided to install a home garden somewhere in the centre of the city. This is in a country with a very conservative attitude to its food culture, where tradition runs deep (although not as deep as to recognize that several staples of the cuisine arrived as interlopers from other lands, roughly 500 years ago.) And because your organization is based in that same city, and has a reputation for knowing about agricultural biodiversity and home gardens, the authorities have asked you to contribute in some way.

You don’t exactly know why the civic authorities are constructing the garden, although you suspect it has something to do with being seen to be green, to care about food and about diversity. And you don’t know what they want, either, or what kind of experience they are planning to offer the visiting public. A gawp at vegetables in the ground rather than in plastic? Surely not. The country hasn’t lost its agrarian roots that completely. Edumacashun? Yeah, but what is the message? You also don’t know what they want. Advice? Expertise? Something to give to visitors?

So you decide to offer them plants that might be found in a home garden far away, specifically, the nutritious African leafy vegetables that you’ve been promoting for better health, incomes and environmental sustainability. But you fear that the civic authorities might not be too keen. You fear they are likely to say something like: “Why should we plant your strange African vegetables in a garden here? What’s the point?”

What one, killer argument would you offer to persuade them?

Nibbles: Biochar, Breeding, Ag exports

- Is biochar the answer for ag? asks the headline. No, but it might be an answer, we reply.

- The Toad points us to a video on Organic Plant Breeding in Denmark.

- Guess where China gets loads of its soybeans. And cotton. And nuts.

Manihot esculenta, I presume?

A blog post from Kew’s archivists on the Zambesi Expedition of 1858-1864 led me to Dr Livingstone’s papers, among which I stumbled on this wonderful letter to Joseph D. Hooker:

A blog post from Kew’s archivists on the Zambesi Expedition of 1858-1864 led me to Dr Livingstone’s papers, among which I stumbled on this wonderful letter to Joseph D. Hooker:

Hadley Green Barnet 11th July 1857

My Dear Dr Hooker

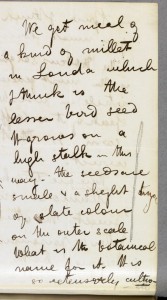

I beg to return you my hearty thanks for your note and the trouble you have been at in deciphering the mere fragments submitted to you. Your willingness to examine anything botanical will certainly make me more anxious to secure something for you in Africa more worthy of your time. We get meal of a kind of millet in Londa which I think is the lesser bird seed. It grows on a high stalk in this way. The seeds are small & a {slight tinge} of slate colour on the outer scale. What is the botanical name for it? It is so extensively cultiv-{ated} in Africa I think you must know. The Holcus Sorghum is the most general article in use. We speak of it as Caffre corn. Is that correct?

There are two kinds of Manioc. One sweet the other bitter & poisonous they are both mentioned in a work by Daniel on the West Coast but I have not that work nearer at hand than Linyanti so I beg to trouble you to tell me the proper names of the two species of Manioc, the Jatropha Manihot and –

As I am boring with questions. Have you the proper names for the melons which form such an important article of support on the Kalahari Desert and of one there which has the flavour of an apple. What is the name of the Palm which when the leaves are broken off gives the idea of it being triangular The ends of the leaf stalks stick on and give it the appearance referred to. A fruit mentioned at the end of Bowdich’s work with by the name Masuka was found by me in very large quantities. It is good. As it seems know can I have the proper name. Now please just attend or not to these questions as it is convenient – though I send them it is not because I think I have any claim on your time or attention – I am only putting you in the way of doing an act of charity to yours &c David Livingstone

Now, how to find the reply?

And with that, dear reader, I take my leave of you for about three weeks, which I will spend not too far, relatively speaking, from where Stanley found Livingstone. In fact, I should already be there…

Nibbles: Huitlacoche, Failure, Food sovereignty, Cold storage, Hunger, Prices

- Mat Kinase discover best smut ever.

- World Bank embraces failure. Now there’s an idea. More here.

- I really don’t have time today for Food sovereignty in Africa: The people’s alternative. Anyone care to interpret?

- Kremlin now tweeting in English. No word yet on Pavlovsk.

- Kenya invests in new market facilities … to improve exports of food.

- Rachel Laudan considers hunger — and celebrates David Livingstone.

- Speaking of which, wanna understand food price spikes? Me too.