- Guess what. Cranberry pests prefer certain varieties.

- If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it. Estimating yield of food crops grown by smallholder farmers from IFPRI.

- CIAT first CG centre to publish peer-reviewed video, on resistance selection. In other news, there are peer-reviewed videos?

- CFTF draws our attention to Jackfruit – Forgotten Kalpavriksha, “a common trope”.

- $3.4 million worth of good news for food security and diversity in the Andes. “Small Andean tuber crops” involved.

- Minor millets star in new film shared by Bioversity.

- Want the Philippines to be self-sufficient in rice? Eat rootcrops. IRRI unavailable for comment.

- Way more than any sensible person will ever want to know about duck and goose semen.

Not all Andean tubers are potatoes

Our regular reader botany professor Eve Emshwiller makes a plea on behalf of some under-appreciated — though not by her — Andean crops.

“That’s a potato?” asks the heading of the photo gallery called “Potato Variety” in the “Food Ark” feature on the loss and conservation of agricultural biodiversity in the latest National Geographic Magazine. Well, actually, no. No, not all of the images shown are potatoes. Five of the eighteen tubers shown are oca, Oxalis tuberosa, one of the three other Andean tuber crops.

As far as I can tell, the gallery of “Uncommon Chickens” and the one for “Rare Cattle” didn’t include any ducks, turkeys, or goats. People would have noticed. In the case of their “Potato Variety” gallery, on the other hand, they missed half of the story. If they’d gotten it right, they would have been able to educate their readers about more than variation within a single crop. They could have gone on to explain about the values of cultivating a diversity of different species, diversity that far exceeds even that in the amazing native Andean potatoes.

The three “minor” tuber crops may not have gained the worldwide importance of the potato, but for a story that focused on the loss of diversity, these other tubers offer even more poignant examples. In my travels in Peru with the germplasm coordinators of INIA (which currently stands for Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria), we came across many places where oca was being abandoned by farmers, due either to severe weevil larvae infestations, or in favor of more marketable crops such as commercial potato varieties.

The three “minor” tuber crops may not have gained the worldwide importance of the potato, but for a story that focused on the loss of diversity, these other tubers offer even more poignant examples. In my travels in Peru with the germplasm coordinators of INIA (which currently stands for Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria), we came across many places where oca was being abandoned by farmers, due either to severe weevil larvae infestations, or in favor of more marketable crops such as commercial potato varieties.

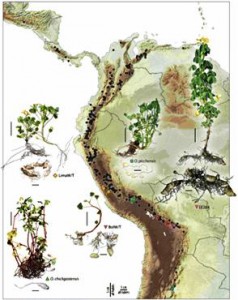

Among the not-so-lost crops from long-before-the-Incas, are a whole bunch of Andean root and tuber crops (often lumped together as ARTs). Ancient Andean people not only domesticated potatoes in all their incredible diversity, but also other tuber crops from three completely different plant families. For those who haven’t met them yet, the three non-potato Andean tubers are (1) oca, Oxalis tuberosa, of the Oxalidaceae, the wood sorrel family; (2) ulluco or papa lisa, Ullucos tuberosus, of the Basellaceae, the same family as Malabar spinach; and (3) mashua, añu, or isañu, Tropaeolum tuberosum, from the Tropaeolaceae, the family of garden nasturtiums. None of these are closely related to each other, or closely related to the family to which potatoes belong (Solanaceae, the nightshade family). No other area of the world domesticated so many different tubers.

Ancient Andean people also domesticated several root crops as well, which are also each from a different plant family. ((Non-professors of botany may like to be reminded that a tuber is a storage organ that is a swollen stem, usually underground, while a root is, well, a root.))

Don’t get me wrong, I think it is absolutely wonderful that the NGS is featuring agricultural biodiversity in their magazine and online. Maybe it bodes well for another spurt of attention to this theme from magazine journalists — don’t they return to it every 25 years or so?

In truth, people are constantly mixing up the Andean tubers, so it is really no surprise that it is happening again. Ulluco is often mistaken for a colorful potato, and it seems as if oca and mashua are mistaken for each other more often than not. Many of the images online that are purporting to be oca, are not. Meanwhile, oca is often mistaken for a native Andean potato, just as in the case of the five tubers of oca (one of them fasciated) that were called potato by National Geographic. So, this is not an unusual case.

But, looking on the bright side, at least CIP has a program on ARTs, now prominently displayed on their newly redesigned website, including a brief introduction to the non-potato Andean tuber crops. And I trust that some of the many celebrations of Peruvian food recently featured on this blog certainly must include dishes made with ARTs, in an effort to overcome these crops’ stigma as “poor person’s tubers.”

In fact, perhaps things are better than I thought. See the image in the Food Ark Photo Gallery that has a caption that begins “A nest of hay preserves harvested potatoes and tubers in Pampallacta, Peru.” Pampallacta is part of the Parque de la Papa, yet the tubers pictured are oca again. So, does that mean that the Parque de la Papa is indeed working to preserve the non-potato Andean tubers as well?

Nibbles: Cryo, Tree diversity, Agroforestry, Seed industry, Trigonella, Ancient MesoAmerica, Niche models

- CIP’s high-tech genebank.

- “The project’s eventual aim is to plant several thousand trees at sites across Perthshire to act as a ‘living gene bank.'” What, because normally genebanks are dead?

- Millennium Seed Bank joins ICRAF’s BusyTrees thing. Which you can follow in about a million different social networking ways.

- Conservation Magazine does a number on crop improvement. Wait, what? Conservation Magazine? Yep, and with teaching resources.

- Fenugreek, barkeep, and make it a double.

- Ancient chocolate and corn routes.

- What species distribution models do you like?

Nibbles: Seed savers, Lemons, Assam Rice, Striga control, Amaranth, Bearded pigs, Banana, Early nutrition

- Seed savers: everyone’s got an angle, from Seeds of Hope and Change to Seed Bank Bingo.

- Italian lemons enjoying a renaissance. In California, natch.

- India registers Assam farmers’ traditional rice varieties. In other news, rice water “is also used as shampoo, according to community elders”.

- US$9 million to “implement and evaluate four approaches” to controlling Striga in Africa. One day we’ll know.

- Denver Botanic Gardens does amaranth.

- Evolution of bearded pigs. Good to know. Good to eat?

- Bioversity banana team guest blogs at Annals of Botany. But surely they have a blog of their own. No, wait…

- Agriculture is bad for your health.

Selling seed of orphan crops in Kenya

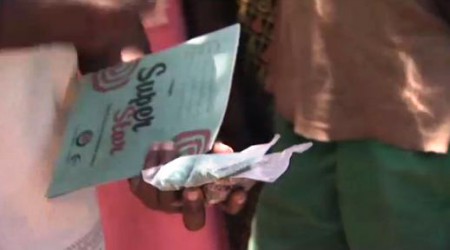

The latest episode of BBC’s Horizon programme deals with a number of things we’ve blogged about here before, for example soil mapping in Africa and biochar. But the payoff for us here is the last segment, which is on a Kenyan seed company called Leldet, which…

…now offers farmers the opportunity to buy different varieties of previously forgotten under-utilised seeds, more suitable for the area. They supply them in smaller quantities so farmers aren’t over reliant on one crop.

Watch it quick, because I don’t know how long it will stay on the site.