I’m ashamed to say that all Seminole names look alike to me. I know it’s a failing, and I’m trying to correct it. But, in the meantime, I could not help but be somewhat alarmed when I saw that a brush fire had destroyed a chunk of Okaloacoochee State Forest in Florida. That’s because I vaguely remembered a wild Cucurbita, endemic to Florida, with a very similar specific epithet. Well, it turned out to be an object lesson in the perils, and occasional advantages, of ignorance.

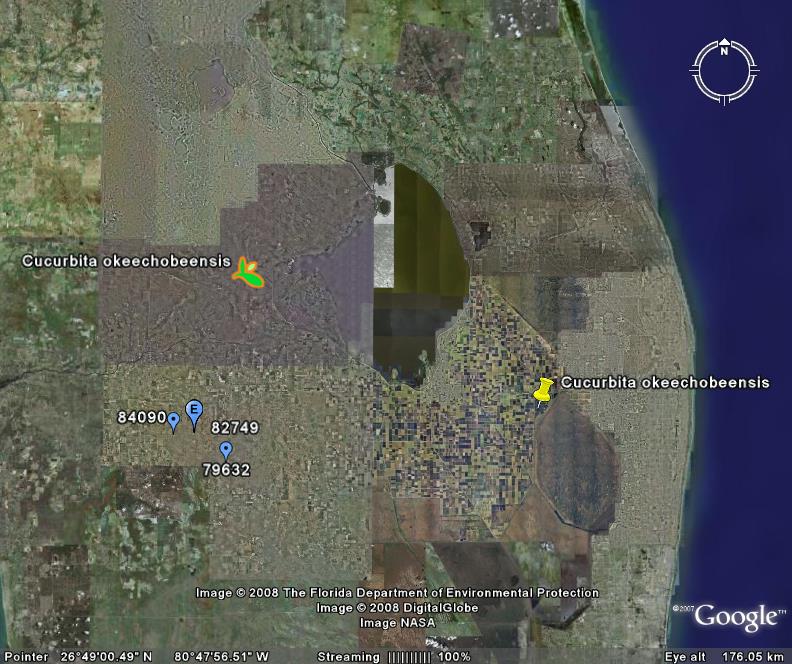

The wild cucurbit is actually Cucurbita okeechobeensis. And that’s the perils part, as “okeechobee” is actually not much like “okaloacoochee.” Pretty embarassing to confuse the two. But gbiffing Cucurbita okeechobeensis, and comparing its distribution with the location of Okaloacoochee State Forest, reveals the advantages part. For it turns out that Okeechobee gourd could well be found in or around the ravaged state forest (blue dots). It’s possible, anyway.

So a little learning can be a useful thing.

Now, I have no idea whether that brush fire actually destroyed, or even threatened, populations of this particular crop wild relative. Maybe someone will tell me. But the point I would like to make is that it would be nice to have a system whereby the locations of threats like fires, floods, new roads etc. could be automatically compared to a dataset of the distribution of crop wild relatives. Globally.

I don’t think technology is a problem. I did the whole thing in Google Earth. The bottleneck is a comprehensive global dataset of the locations (actual or predicted) of populations of crop wild relatives. Hopefully that’s what the CWR Portal will become in time.