- At last, sustainable clarinets!

- Hummus war gets serious. All that seratonin not helping?

- “Hearts of oak are our ships, jolly tars are our men.” Simon Schama on Quercus robur. Note to BBC: learn how to write species names.

- Pop quiz: Some 20,000 tons of this seed were delivered by Aztec farmers in annual tribute to their emperor, Montezuma. Now big in the US, according to NYTimes piece. From 1984.

The Three-hundred-variety mango of Malihabad

Another reflection on a remarkable Indian mango tree from our friend Bhuwon Sthapit of Bioversity International.

It is hard to believe that a farmer can have as a hobby the grafting of multiple varietal scions of interesting and unique mango diversity on to a single tree. I certainly did not believe it. Until I saw the orchard of Haji Kaleem Ullaj Khan in Malihabad. There he maintains several trees with many varieties grafted onto them as sources of scions for his mango nurseries. A good and reliable source of scions is essential to run a successful and credible mango nursery, but to have a conventional scion block is expensive in terms of maintenance and land.

The son of the magician grafter, Najmi, showed me two very remarkable mango trees. One is said to be 100 years old and is named Al-Muqarrar. It has had more than 300 varieties of mango skilfully grafted onto it by Najmi’s father father. The other, younger tree has more than 150 mango genotypes grafted on to it. Each branch looks like a different tree! Both trees are bearing fruits of different colour, shape and size, and at different times.

Born in 1945, Haji Kaleem Ullaj Khan does not have any academic horticultural degrees, but he is widely renowned in India for his skills and knowledge in multiple grafting on a single tree. He was awarded the title of Udhyan Pandit (Professor of the Orchard) by a former President of India. He has also presented a mango tree bearing 54 varieties to the current President for the premises of the Mughal Garden of Rastrapati Bhavan. He has been acknowledged by many high-profile visitors from abroad and also decorated with the Padamashri award. His name is recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records for his grafting feats.

Abdullah Nursery is famous in Malihabad and throughout India for Haji Kaleem Ullaj Khan’s innovations, and markets saplings of commercial varieties to such distant places of Bhutan, Nepal and Bangladesh. Unlike government research stations, Haji Kaleem Ullaj Khan uses ground layering for his propagation for most commercial saplings, and veneer or wedge grafting in special cases. He has also grafted a guava tree that flowers and fruits all year round, which is another attraction for the nursery.

Abdullah Nursery is famous in Malihabad and throughout India for Haji Kaleem Ullaj Khan’s innovations, and markets saplings of commercial varieties to such distant places of Bhutan, Nepal and Bangladesh. Unlike government research stations, Haji Kaleem Ullaj Khan uses ground layering for his propagation for most commercial saplings, and veneer or wedge grafting in special cases. He has also grafted a guava tree that flowers and fruits all year round, which is another attraction for the nursery.

This innovation borne out of local need is a promising way for nurseries to maintain many scions at relatively low cost. However, this can be a high risk practice, because many varieties depend on one mother tree’s survival. It is thus important to have adequate safety duplication or maintain some scion material trees separately. Multiple variety grafting can also be used as an attraction in agrotourism, and for innovative marketing of diversity in urban and home gardens. This will create a new market for nursery growers and raise public interest in the diversity of mangoes. This activity has been conceptualized in the context of the UNEP/GEF project Conservation and Sustainable Use of Tropical Fruit Tree Diversity in India.

Nibbles: Date gin, Papaya, Grains, Swiss cheese, Mini-horse

- Sudan’s date-gin brewers thrive despite Sharia. There’s date gin? h/t Brendan.

- A very interesting account of virus resistant papayas.

- Whole grains are good for you. And could be better.

- Swiss cow culture.

- Like pocket pigs? You’re gonna love the pocket horse.

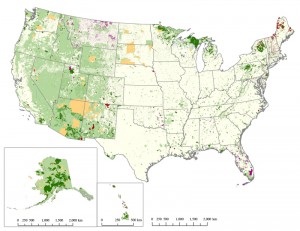

New protected areas dataset released into wild

Speaking of mashing up funky GIS datasets with crop wild relatives distribution data — and we do; a lot — how long will it be before someone does it with the new US protected areas database?

Hairy pig hits limelight

They don’t say whether it is the famous Lincolnshire Curly Coat, but it looks like it might be. 1 Now, if only they could make them pocket-sized…

Thanks, Cary.

UPDATE (17 Fe. 2016): Well, “they” were the LA Times, and both the story and video to which we linked back in 2010 are no more. But the “sheep pig” in question probably was the Mangalitza, and the story of how it was rescued from oblivion is actually pretty cool.