- High-level agricultural scientists thinks high agricultural science will feed the world. Oh, and smart policies.

- This new rice would qualify, I suspect.

- Participatory varietal selection manual revised to take women into account. Someone mention high science?

- No such manual needed in India, it seems.

- The banana-is-doomed story sure has legs. Or hands.

- What did the Inkas ever do for us?

- Is agriculture diverse enough? That is the question.

- Yerba mate gets sequenced. Because it can be.

- Following an Indian cucumber down the value chain.

- Thank your lucky stars for this weedy-looking tomato wild relative.

- “We’re interested in the color, shape and sizes of the vegetables from 400 years ago, compared to modern cultivars of the same vegetables: the deep sutures on cantaloupe in Italian art of the Renaissance or the lack of pigmentation in pictures of watermelon compared to today.”

- Quite a bit of agrobiodiversity featured in Day of Archaeology. Nice idea.

Brainfood: Grassland diversity, Potato diversity, English CWR, Genetic rescue, Saffron diversity, Lac, Cereal domestication, Turkish pea, Pathogen genomes, Rose fragrance, African cheese

- Worldwide evidence of a unimodal relationship between productivity and plant species richness. Grassland richness maximal at intermediate productivity levels.

- Cytoplasmic genome types of European potatoes and their effects on complex agronomic traits. Interesting relationships between cytoplasmic type on one hand and tuber starch content and resistance to late blight on other.

- Enhancing the Conservation of Crop Wild Relatives in England. 148 priority species, half of them not in ex situ at all. But there’s no excuse for that now.

- Genetic rescue to the rescue. Meaning an increase in population fitness, especially of rare species, owing to new alleles. Genomics will help by choosing the new alleles better, and monitoring the results.

- Diversity and relationships of Crocus sativus and its relatives analysed by IRAPs. No variation in the allotriploid cultigen, lots in the closely related species. Let the resynthesis begin.

- Economic analysis of Kusmi lac production on Zizyphus mauritiana (Lamb.) under different fertilizer treatments. That would be the scarlet resin secreted by some insects. NPK needed. No word on genetic differences.

- Parallel Domestication of the Heading Date 1 Gene in Cereals. Same QTL in sorghum, foxtail millet and rice, but different alterations of it. Multiple domestication for sorghum, single for foxtail millet.

- DNA based iPBS-retrotransposon markers for investigating the population structure of pea (Pisum sativum) germplasm from Turkey. No geographic structure for the landraces.

- The two-speed genomes of filamentous pathogens: waltz with plants. Fungi and oomycetes quite different genetically, but both have regions of genome which change rapidly to make them good pathogens. Bastards.

- The flowering of a new scent pathway in rose. Can we have our nice-smelling roses back now, please?

- AFLP assessment of the genetic diversity of Calotropis procera (Apocynaceae) in the West Africa region (Benin). Not just a weed, used in cheese-making, of all things.

Brainfood: Domestication stats, Apple vulnerability, Himalayan fermentation, Tree diversity, Grasslands double, Shiitake cultivation, Lablab core, Ethiopian sweet potato, Georgian grape

- A domestication assessment of the big five plant families. Half of cultivated plants are legumes, a third grasses.

- The vulnerability of US apple (Malus) genetic resources. Moderate.

- Microorganisms associated with amylolytic starters and traditional fermented alcoholic beverages of north western Himalayas in India. Veritable microbial communities.

- Spatial incongruence among hotspots and complementary areas of tree diversity in southern Africa. It’s not just about the hotspots.

- Integrating Agricultural and Ecological Goals into the Management of Species-Rich Grasslands: Learning from the Flowering Meadows Competition in France. Gotta document the synergies.

- Genetic–geographic correlation revealed across a broad European ecotypic sample of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) using array-based SNP genotyping. Strong structure both with latitude and longitude. Wonder if the Flowering Meadows competition took that into account.

- Interactions of knowledge systems in shiitake mushroom production: a case study on the Noto Peninsula, Japan. Tradition is not always a totally good thing.

- Development of Core Sets of Dolichos Bean (Lablab purpureus L. Sweet) Germplasm. Heuristic is better. But is it PowerCore?

- Genetic Diversity of Local and Introduced Sweet Potato [Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.] Collections for Agro-morphology and Physicochemical Attributes in Ethiopia. The improved varieties are not all that great. But there were only two of them. And the local landraces were not necessarily the best.

- Study of genetic variability in Vitis vinifera L. germplasm by high-throughput Vitis18kSNP array: the case of Georgian genetic resources. Some differentiation between wild and cultivated, but significant overlap.

Invisible Angola

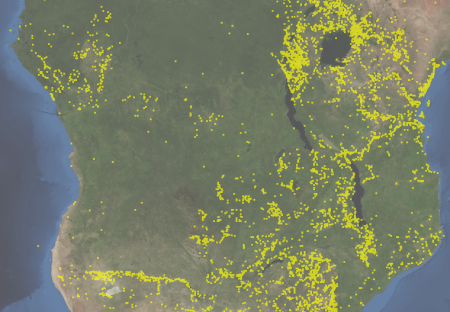

Kew botanist David Goyder had a thought-provoking blog post a couple of days back describing the relative lack of floristic data from Angola. Here’s his map of plant collection data for southern Africa, from GBIF:

Angola emerges quite clearly as a gap, particularly the interior. There’s lots of reasons for that, not least landmines, as Goyder points out, and there are also efforts underway to redress the situation. But the thought that the map provoked in me was, of course, whether the situation was similar for crops. So here’s what Genesys knows about crop germaplasm collections in southern Africa:

It seems the answer is a pretty resounding yes. Again, you can clearly trace the borders of Angola by where the genebank accessions end. There is, in fact, though, a very active national genebank in Angola, which has been collecting the country’s crop diversity for years, landmines or no landmines:

A total of 441 accessions were collected during a mult-crop collection in Huila province, Namibi province and Malanga province in 2004. With these collections, NPGRC now has a representative sample from 55% of the total number of districts in the country and representing 60% of the recognized agricultural zones (MIIA).

But when will we be able to see the data?

Rational botanical gardens

The 7th European Botanic Gardens Congress is on this week, in Paris. You can follow it in all the usual ways, or most of them anyway. I was struck by this tweet from the opening day, of a slide from the presentation by new BGCI director Paul Smith. Sounds a lot like what we’re trying to do with crop genebanks around the world too.

La importancia de los #jardines #botánicos #EurogardVII by Smith Paul pic.twitter.com/ULQanwdBCM

— Aso.AmigosConcepcion (@AAJBHC) July 6, 2015

There’s a botanical garden that is conserving one crop almost single-handedly, but Diane Ragone, who’s in charge of the the National Tropical Botanical Garden and its breadfruit collection, is at a different, and I suspect more entertaining, conference in Trinidad.

LATER: Paul’s vision is more fully set out here.