Columbia Basin pygmy rabbits reintroduced into their native habitat in the state of Washington are finally breeding, raising hopes that this endangered species will recover. Ok, so as wild relatives of a domesticated species go, this one is a fairly remote one, but who knew that “the domestic Oryctolagus cuniculus is believed to have originated in French monasteries in the late first millennium?”

Invasion of the agro-bread-heads

This blog — or more accurately the topic it covers — has seen a recent flurry of economic activity. And while that may not be attractive to all, the fact is that money does make the world go round. Make something cheaper or more profitable, and people are liable to do more of that thing.

Latest entrant is a Policy Forum piece in Science ((Jordan et al. (2007), Sustainable Development of the Agricultural Bio-Economy. Science 316:1570-1. DOI: 10.1126/science.1141700)) that argues that policies that favour “multifunctional production systems” — systems that produce standard commodities and ecological services — will be profitable and will support a more sustainable agriculture.

The argument is reasonably straightforward. First, the authors note the trend towards growing biomass. Then they note that monocultures of fuel are likely to be just as bad as monocultures of food and fibre. They look at the amount handed out in subsidies and the often perverse impacts that has on the environment and on societies.

Despite troubling implications of these current trends, research and development (R&D) and policy have focused on maximizing biomass production and optimizing its use, with far less emphasis on evaluation of environmental, social, and economic performance. This imbalance may provoke many interest groups to oppose growth of such an agricultural bio-economy.

After examples of the kinds of multifunctional production systems they have in mind they outline some of the various ways in such biodiversity delivers valuable benefits.

There is mounting evidence that these systems can produce certain ecological services more efficiently and effectively than agroecosystems based on annual crops. Examples include (i) soil and nitrogen loss rates from perennial crops are less than 5% of those in annual crops; (ii) perennial cropping systems have greater capacity to sequester greenhouse gases than annual-based systems; (iii) in certain scenarios, some perennial crops appear more resilient to climate change than annuals, e.g., increases of 3°to 8°C are predicted to increase North American yields of the perennial crop switchgrass (Panicum virgatum); and, among species of concern for conservation, 48% increased in abundance when on-farm perennial land cover was increased in European Union incentive programs.

The final plank in the argument is a rough and ready survey of the value of those benefits, which I won’t quote. Take it from me, they are large.

So much for the foundations. On them Jordan and colleagues build a solid policy suggestion. Build a couple of large projects — 5000 square kilometres — and put some of the government money that naturally flows farming’s way into establishing genuine multifunctional systems and assessing properly the pros and cons of this approach from a variety of perspectives.

Seems like a pretty sound idea, and one on which I feel comment is largely superfluous. If the US government really wants to burnish its green credentials, it should just do it.

Agricultural subsidies in 2005 exceeded $24 billion, and the 2007 farm bill deliberations should highlight how these federal dollars could better achieve national priorities. In particular, the new farm bill should provide the agricultural R&D infrastructure with incentives to evaluate multifunctional production as a basis for a sustainable agricultural bio-economy. We judge that this can be done with very modest public investments (~$20 million annually). A variety of strong political constituencies now expects a very different set of outputs from agriculture, and the U.S. farm sector could meet many of these expectations by harnessing the capacities of multifunctional landscapes.

Oscar Wilde said that “a cynic knows the price of everything and the value of nothing”. I say that those responsible for farm subsidies know neither costs nor values.

The value of organic farming

Organic farming again today. I’ve come across two papers from opposite ends of the world on this subject which it may be worth discussing together.

The first, from New Zealand, describes an experimental attempt to put a value on the ecosystem services provided by different pieces of arable land near Canterbury. That’s interesting – and difficult – enough, but the authors did this for both conventional farms and neighbouring organic farms. Values for the following services were calculated: biological control of pests, soil formation, mineralization of plant nutrients, pollination, services provided by shelterbelts and hedges, hydrological flow, aesthetics, food, raw materials (fibre, fuelwood, pharmaceuticals etc.), carbon accumulation, nitrogen fixation and soil fertility.

The results were that organic fields provided ecosystem services to the tune of US$ 4,600 per hectare per year, compared to US$ 3,680 for conventional fields: “there were significant differences between organic and conventional fields for the economic value of some ecosystem services.†Now, that must be associated with increased (agro)-biodiversity in the organic fields – more natural enemies, more pollinators, more earthworms, more medicinal plants etc. – but this was not measured in the study.

The other paper did compare diversity in organic and conventional farms, but only for plant at the species level, and no attempt was made to calculate values. Working in the south of England, the authors found significantly more plant diversity in organic arable fields as compared to conventional fields – though no differences in the plant diversity of other types of habitats within farms, such as woodland fragments and hedgerows.

I suppose what we need is a combination of these approaches, bringing together diversity assessment with valuation. Because in the end we’re only going to be able to conserve biodiversity if we can adequately value it.

Seed appeal

This is a new one to me. Prof. Dr. Willem van Cotthem is asking his blog’s readers to donate spare seeds of melon, watermelon and pigeon pea. What’s more, he just wants the melon seeds you would otherwise throw away. Given how promiscuous most melons can be, the seeds are going to represent a bonanza of agricultural biodiversity.

This is why he wants the seeds:

All the seeds will be used for fruit production in arid or semi-arid regions, where we treat the soil with a water stocking soil conditioner, so that the rural people can grow these plants with a minimum of water. I promise to publish pictures on the results obtained with your seeds.

Isn’t this a very nice way to contribute to the success of a humanitarian project? The more melons and water melons you eat, the more poor rural people will get chances to grow them in their family garden and the kids will grow them in their school garden.

And the more varieties will be exposed to those testing conditions. I wonder what will emerge from the mix?

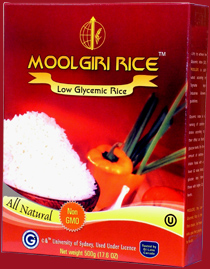

Rice for diabetics launched

There’s a very odd story in The Hindu. It describes the launch of a “new variety of low glycemic rice“. Low glycemic foods are digested more slowly and create less of a spike in blood sugar, and have been pushed for diabetics, weight loss and sundry other benefits. One of the nice things about basmati rice, quite apart from its wonderful fragrance and flavour, is a relatively low glycemic index (although strictly speaking it has a medium GI). The new rice is not a basmati rice.

The rice, called Moolgiri, is marketed by Taj Mahal Agro Industries, and according to independent tests does indeed have a glycemic index of 54, just in the “low” category. That could be very interesting news, especially if Moolgiri is one of the many thousands of rice varieties that just happens to have this property. But the story got murkier the more I looked into it.

The rice, called Moolgiri, is marketed by Taj Mahal Agro Industries, and according to independent tests does indeed have a glycemic index of 54, just in the “low” category. That could be very interesting news, especially if Moolgiri is one of the many thousands of rice varieties that just happens to have this property. But the story got murkier the more I looked into it.

For a start, it is not a variety but a trade name. A rice with its own web site! There’s all kinds of information there, but not an awful lot about what exactly makes Moolgiri special. We learn that:

Moolgiri rice is a clear blend of tradition and technology. After ten years of continuous research Tajmahal Agro industries identified suitable traditional grain and developed innovative process to achieve Moolgiri.

There’s also a lot about how it is grown, tested and so on. But you have to dig deeper to discover that the variety itself is called manisamba, and that it

undergoes a patented process to remove 70% of the starch content.

So I did a little more digging, in SINGER, and discovered that there is a rice called Pamani samba, that it was collected in India, and that there is a sample (of unknown status) in the genebank at the International Rice Research Institute. And there the trail goes cold. There seems to be no further information about this wonderful variety. No “special traits” are noted.

All of which is both satisfying and unsatisfying (rather like a meal of high GI rice?). I found the variety. But no more about it. Maybe the special patented process could do the same to any old rice? I doubt it, but you never know. And maybe there are actually rice varieties out there that would have a low GI without a special patented process. I think that’s what I had been hoping, that there existed a rice that, polished and purified, would be have a naturally low glycemic index. Alas, it ain’t so.