Possibly in response to the previous post about ecological entrepreneurs, a reader recommends The Jamlady Cookbook, by Beverly Ellen Schoonmaker Alfeld. ((That’s not a typo; there’s no space in the title, which is why I am giving full details of the author’s name.)) I haven’t seen it, but it contains advice and recipes for using every conceivable type of fruit. Maybe it will inspire others to become micro-entrepreneurs, although my understanding is that in Europe at any rate, if you propose to prepare food for sale, you have to jump through all sorts of hoops to do so legally.

One thing that has struck me on recent jaunts through the Italian countryside had been the profusion of fluffy white flowers on the elder (Sambucus nigra) bushes. Of course, the Italians make Sambuca from elder, though I can detect almost no elderflower or elderberry flavour in there, only the anise note of licorice, its other main ingredient (beside alcohol). But they do not seem to know about either elderflower champagne or elderflower cordial. I must put them to rights. Maybe they do know elderflower fritters; I’ve been unable to find out. Here’s just the book to help: The Elder in history, myth and cookery, from the ever-wonderful Prospect Books.

While we’re on the subject of books for this sort of thing, I have two stand-bys, admittedly unused for the past few years as I have not had anywhere to use them. One is Putting Food By, by Ruth Hertzberg, Beatrice Vaughan and Janet Greene. If it isn’t in there, it isn’t worth doing. The other is an astonishing book from Britain’s old Agriculture and Food Research Council (when such things mattered). Home Preservation of Fruit and Vegetables contains a good amount of sensible advice and practical recipes.

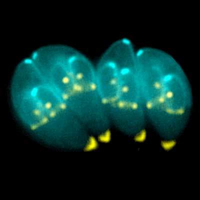

Toxoplasma gondii is a protozoan ((From H. Michael Kubisch. Photograph shows toxoplasma dividing into daughter cells. Image provided by Ke Hu and John Murray. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020020.g001)) that can infect birds and mammals — although it can reproduce sexually only in domestic and wild cats. It has been estimated that about

Toxoplasma gondii is a protozoan ((From H. Michael Kubisch. Photograph shows toxoplasma dividing into daughter cells. Image provided by Ke Hu and John Murray. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020020.g001)) that can infect birds and mammals — although it can reproduce sexually only in domestic and wild cats. It has been estimated that about