- Unlocking the potential of wild rice to bring missing nutrition to elite grains. A solution for better nutrition.

- Characterization of Oryza glaberrima derived genetic resources for stagnant flooding tolerance in interspecific rice pre-breeding populations. A solution for too much water.

- Strengthening Global Rice Germplasm Sharing: Insights from the INGER Platform. A solution for getting the above solutions out to those who need them.

- Comprehensive nutritional and antinutritional characterization of pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan): Insights into genotypic diversity and protein quality. A solution for better protein.

- Exploring the agro-morphological performance of mini core collection of finger millet [Eleusine coracana (L.) Gaertn] germplasm under sodic condition. A solution for high sodium in soils.

- A Public Private Partnership in Plant Breeding — The Case of Irish Malting Barley. A solution for Irish malt.

- The business case for grasspea in Ethiopia: An action plan to provide Ethiopian farmers with a safe, nutritious and climate-smart protein source. A solution for ODAP. Which will still need to be sold, though.

- Harnessing historical genebank data to accelerate pea breeding. A solution for cold, and more.

- Genetic basis of phenotypic diversity in C. stenophylla: a stepping stone for climate-adapted coffee cultivar development. A solution for heat.

- A phylogenetic approach to prioritising crop wild relatives in Brassiceae (Brassicaceae) for breeding applications. A solution for finding solutions.

‘Cima di cola’ reaches a milestone, apparently

So it seems the first vegetable variety from Puglia has been added to Italy’s Registro nazionale delle varietà da conservazione, or National Register of Conservation Varieties.

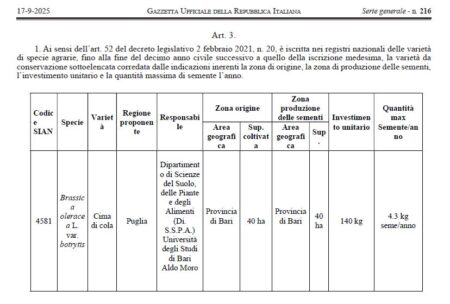

The ‘Cima di cola’, a cauliflower variety historically linked to the agricultural tradition of Bari, received official recognition by Ministerial Decree of 9 September 2025, published in the Official Gazette No. 216 of 17 September 2025, which will allow its conservation and promotion also at the commercial level.

I know this because of a post on Facebook from an outfit called Biodiversità delle specie orticole della Puglia (BiodiverSO), translated above. Which unfortunately doesn’t include a link, but does provide this screenshot of Italy’s Official Gazette to prove its point.

Here’s more from the BiodiverSO post.

The inclusion of the ‘Cima di cola’ among conservation varieties is not only an institutional achievement, but also an act of recognition toward those who have preserved its seeds and traditions over the years; a milestone that opens new opportunities for scientific, educational, and gastronomic promotion, which we look forward to sharing with you.

Doubtless.

Which is why I was pretty disappointed to find that the Registro nazionale delle varietà di specie agrarie ed ortive is not actually up to date, so doesn’t yet include ‘Cima di cola’.

Quite apart from not being exactly easy to find. And there was also nothing in the relevant news section, which is actually on a different website, but nevermind.

Anyway, there are 135 “Varietà da Conservazione” registered therein. It’s unclear how to obtain seeds.

LATER: Thanks to Filippo Guzzon for advising me that ‘Cima di cola’ is indeed on the list. I was looking for it under the wrong crop name :(

A concerted effort to conserve edible plants kicks off

Do you remember a Nibble from a few days back on how wild food ingredients are making their way into school meals in India? You may have wondered at the time if there was some kind of global initiative to conserve such wild edible plants. Because they can fall between the two stools1 of crop genebanks on one side and botanical gardens on the other.

Well, there wasn’t then, but there is now. Say hello the Global Conservation Consortium for Food Plants. Just launched, with the NY Botanical Garden hosting the secretariat.

Good news from the genebank world?

As you may have noticed, I’ve been on a mission lately to document in Brainfood the progress that genebanks are making. Because I needed some good vibes, you know? So last week there was a post on how the “software” of genebanks — that is, how they function and are managed — is being upgraded. The week before there was a round-up of core collections, one of the main things genebanks do to get their contents used more, showing that this oldish technology is still up and running, and even occasionally making a difference. And then this week I did a Brainfood on the new “hardware” some genebanks are using — or could be using. Meaning cool modern tools of different kinds to help out at difference stages of the conservation-to-use workflow. But I’m sure I missed some things. Surely I missed some things? Let me know in the comments. Please. For the vibes, you understand.

Brainfood: Taxonomic identification, Niche mapping, Harvest tracking, Drones, Phenomics, Yield analysis

- Review of herbarium plant identification of crop wild relatives using convolutional neural network models. Cool tech helps you figure out which species is which. Now you can map them properly I guess.

- Habitat prediction mapping for prioritizing germplasm collection areas of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp) in India using BioClim model. Having mapped them, another cool tech helps you figure out where to collect them.

- Harvest Date Monitoring in Cereal Fields at Large Scale Using Dense Stacks of Sentinel-2 Imagery Validated by Real Time Kinematic Positioning Data. And when.

- Drone methods and educational resources for plant science and agriculture. In the field, cool tech could help you find and collect them. And not just that…

- Foliar disease resistance phenomics of fungal pathogens: image-based approaches for mapping quantitative resistance in cereal germplasm. Having collected them, more cool tech helps you evaluate them.

- Machine learning reveals drivers of yield sustainability in five decades of continuous rice cropping. Finally, having evaluated them over many years, cool tech helps you figure out what’s going on.