You see a grumpy plant biologist. Ask them what stomata? #PlantDay @RoyalSocBio pic.twitter.com/hM7MRyx9my

— Mr C (@mintchemistry) May 17, 2017

Indian nutrition and crop diversity link ready to be explored

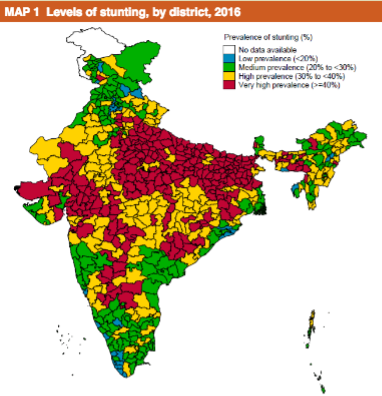

Is there a relationship between levels of stunting in Indian districts…

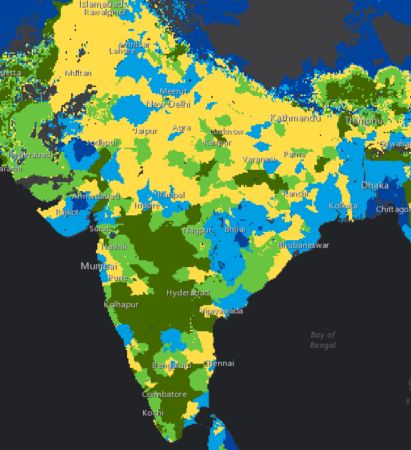

…and crop diversity in their farming systems (blue low, green high)?

I have no idea. But I think we should be told.

New CGIAR portfolio off and running

CGIAR launched its new portfolio yesterday, there was a Twitter chat thing, and I wrote a blog post about the Genebanks Platform. Not many people hurt.

How genetic improvement and crop intensification improve wellbeing

Featured: Mapping crops

Glenn is ready to take up our challenge on crop distribution mapping:

I suppose that you could use “big data” & machine learning to find individual crop patterns in all that data. I think that some people are doing this kind of thing, but it’s private sector stuff. The global crop maps rely too heavily on data from surveys and censuses, and all the problems that come with those in terms of standardizing across countries.

Kinda. Sorta.

Featured: Dynamic landraces

Susan Bragdon sounds frustrated:

It seems like the studies at least both confirm the dynamism in managing and developing landraces. One would expect some to go out of use and new landraces to emerge (good reason, amongst others, to have ex situ collections to have “snap shots” over time). I know I am saying nothing new to this audience, but in international circles — even some parts of the international world specifically addressing biological diversity (I can tell you about the Human Rights Council Resolution on Biological Diversity adopted in March as an example) — the idea that farmers are more than preserving a static pool of genetic resources is not well-understood. And don’t get me going on understanding the links to health, employment, peace…

What brought this on now, Susan? And if you want a platform for discussing those links, we do take guest posts.