FAO issued its report The future of food and agriculture: Trends and challenges a couple of months back, but I don’t think we mentioned it at the time, at least not in any detail.

Without a push to invest in and retool food systems, far too many people will still be hungry in 2030 — the year by which the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda has targeted the eradication of chronic food insecurity and malnutrition, the report warns.

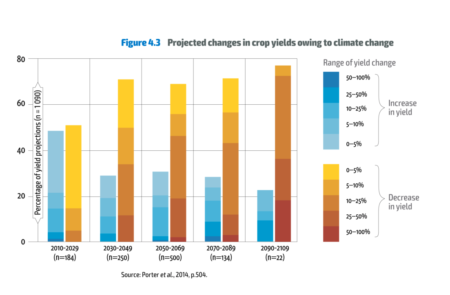

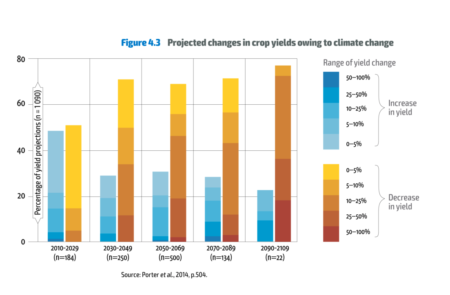

I come back to it now because of a useful digest that Ensia has just put out, summarizing the trends analyzed by the report in 12 handy graphs, of which this is perhaps the scariest.

What’s to be done? There’s much talk in the report about “innovative systems that protect and enhance the natural resource base, while increasing productivity” and a “transformative process towards ‘holistic’ approaches, such as agroecology, agro-forestry, climate-smart agriculture and conservation agriculture, which also build upon indigenous and traditional knowledge.” Nothing specifically on conserving crop diversity, however, though I suppose it could be implied in some of the above. There was this, though:

On the path to sustainable development, all countries are interdependent. One of the greatest challenges is achieving coherent, effective national and international governance, with clear development objectives and commitment to achieving them. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development embodies such a vision – one that goes beyond the divide of ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries. Sustainable development is a universal challenge and the collective responsibility for all countries, requiring fundamental changes in the way all societies produce and consume.

The International Treaty on PGRFA, although also not mentioned by name, is of course predicated on this very interdependence, and coincidentally there was a major development on that last week:

Switzerland proposes that a new paragraph should be added below the current list of crops contained in Annex I. The new paragraph should read as follows:

“In addition to the Food Crops and Forages listed above, and in furtherance of the objectives and scope of the International Treaty, the Multilateral System shall cover all other plant genetic resources for food and agriculture in accordance with Article 3 of the International Treaty.”

Switzerland requests the Secretary of the International Treaty to communicate this submission prior to the next ordinary session of the Governing Body to all Contracting Parties in accordance with Art. 23.2 of the International Treaty.

That should make for an interesting meeting of the Governing Body later this year, and put the talk of “collective responsibility” to the test.