Congratulations to the Italian company Sa Laurera for receiving the 2016 Arca Deli Award for its Sardinian grasspea variety Inchixa.

In 2016, the SAVE Foundation announced the Arca Deli Award which is dedicated to products derived from the cultivation of local rare or endangered varieties that were recovered and maintained on a farm and are appropriately valued. We chose to compete with our Inchixa.

At the annual meeting of the foundation held in Metlika, Slovenia in September the SAVE jury met to evaluate products that had entered the competition.

A few weeks ago, we were informed that we are among the six winners! Sa Laurera is the only Italian company to have won the Arca Deli Award 2016, and our grasspea is the first Sardinian pulse to receive international recognition.

From a toxic plant, contraindicated for human consumption, to an interesting crop that deserves to be reassessed for its nutritional and nutraceutical features: It is particularly rich in protein, containing around 30g of protein per 100g of edible seeds, and seems to have positive effects for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases and osteoporosis.

The Inchixa example shows that small-scale farm work can be a starting point for the recovery and development of forgotten foods.

Preparing grasspea to eat is hard work, so “recovery and development” of this “forgotten food” must have been quite a challenge. But not an insurmountable one, apparently.

In Sardinia, new generations and urban dwellers, who are increasingly sensitive to issues related to health, food and local gastronomic traditions, not only appreciate the legume but actively seek it out.

I couldn’t find Inchixa in any of the usual databases, but “the name comes from from the Catalan word Guixa,” and there are lots of accessions of things with this name in the Spanish genebank.

Other Sardinian local names for grasspea are Denti de bècia, Piseddu, Pisu-faa, Pisu a tres atzas. Propagation material used to start the recovery of landrace derives from small-scale cultivations of our relatives, who have mostly cultivated this crop for self-consumption.

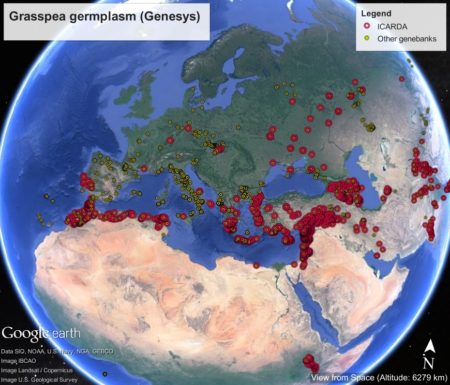

Piseddu is the only one of these which I found on Genesys, collected in Sardinia and conserved in Germany. Thank goodness for those relatives, but I hope they put all of these landraces in a genebank somewhere. Perhaps ICARDA’s? They have very little from Italy, but lots from the rest of the area of the crop (click to enlarge the map).