We’ve been contacted by Alexander Wankel of Pachakuti Foods with news of an intriguing Kickstarter campaign. Pachakuti is…

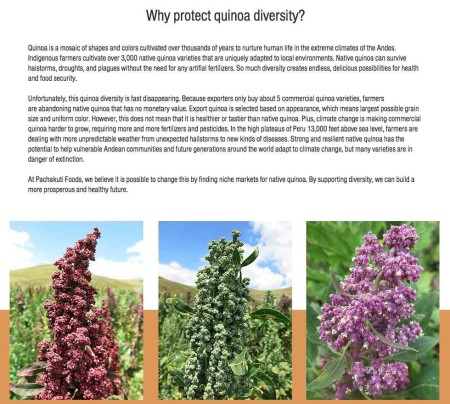

…a social enterprise committed to sourcing rare Andean superfoods directly from farmers to create unique products for a healthier life and a better world. By finding markets for underutilized crops, we strive to support biodiversity while providing a fair income for Andean farmers.

The unique product that is the focus of the Kickstarter is, of all things, quinoa milk.

Pachakuti Foods is launching the first quinoa milk made with carefully selected native quinoa varieties that have a naturally milky flavor and texture. Made from some of the yummiest quinoa in Peru, our quinoa milk is richer and creamier than quinoa milk made from conventional quinoa that is currently on the market. It is 100% vegan, gluten free, and contains high quality proteins with all the essential amino acids that the body needs.

They’re about half-way to their goal, which is $15,000.

This Kickstarter campaign is our first opportunity to hit the ground running, both by helping us raise money as well as tell the story of why quinoa diversity is important.

So help them out, if you’re so inclined. Or maybe point them to a bank that might be interested in giving them a business loan.