- High Royal Jelly-Producing Honeybees (Apis mellifera ligustica) (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in China. China supplies 90% of the global market?

- Taking Advantage of Natural Biodiversity for Wine Making: The WILDWINE Project. Back to the future, via yeast diversity.

- Conservation of Landrace: The Key Role of the Value for Agrobiodiversity Conservation. An Application on Ancient Tomatoes Varieties. Fancy maths shows farmer maintaining heirloom tomato variety in Perugia could be charging more.

- Are changes in global oil production influencing the rate of deforestation and biodiversity loss? Less oil production, more agricultural expansion, more biodiversity loss.

- Grazing vs. mowing: A meta-analysis of biodiversity benefits for grassland management. Grazing. Probably. The data sucks.

- Maize diversity associated with social origin and environmental variation in Southern Mexico. Ethnicity trumps altitude in genetic patterning. Morphology is all over the place.

- Genetics in conservation management: Revised recommendations for the 50/500 rules, Red List criteria and population viability analyses. One we missed. 100/1000 is the new 50/500. Multiply by 10 for census population sizes to avoid inbreeding and retain evolutionary potential, respectively.

- Advances in genomics for the improvement of quality in Coffee. We’ll need to sequence the wild species too.

Cooperation-88 featured in National Geographic

Farmers once cultivated a wider array of genetically diverse crop varieties, but modern industrialized agriculture has focused mainly on a commercially successful few. Now a rush is on to save the old varieties—which could hold genetic keys to de- veloping crops that can adapt to climate change. “No country is self-sufficient with its plant genetic resources,” says Francisco Lopez, of the secretariat of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The group oversees the exchange of seeds and other plant materials that are stored in the world’s 1,750 gene banks. — Kelsey Nowakowski

That’s the introduction to a nice feature in the current National Geographic, part of the series The Future of Food. Problem is, I can’t find it online any more. I swear it was there, but it’s not any more. Maybe it was a copyright issue, and it will come back later, when National Gepgraphic is good and ready.

Anyway, the piece is entitled The Potato Challenge:

Potatoes in southwestern China had long been plagued by disease, so scientists began searching for blight-resistant varieties that could be grown in tropical highlands. By the mid-1990s researchers at Yunnan Normal University in China and the International Potato Center (CIP) in Peru had created a new resistant spud using Indian and Filipino potatoes.

The resistant spud is Cooperation-88, of course, and if and when the piece finds its way online you’ll be able to admire some fancy infographics summarizing how it was developed and the impact it has had.

Farmer-saved seeds are not fake

“Fake seeds” have been making the news in Uganda recently, on the back of a World Bank paper:

Of the many factors that keep small-scale Ugandan farmers poor, seed counterfeiting may be the least understood. Passing under the radar of the international development sector, a whole illegal industry has developed in Uganda, cheating farmers by selling them seeds that promise high yields but fail to germinate at all – with results that can be disastrous.

Counterfeiting gangs have learned to dye regular maize with the characteristic pinkish orange colour of industrially processed maize seed, duping farmers into paying good money for seed that just won’t grow. The result is a crisis of confidence in commercially available high-yield seed.

So it’s good to see one of the dozens of Youth Agripreneurs Project proposals being considered by GFAR tackling the issue.

Problem is, as Ola Westengen points out in a tweet, the project seems to be confused about what “fake” or “counterfeit” seeds are.

Is this project confusing "seeds from informal system" with "fake seeds"? Important dif. @AgroBioDiverse @GFARforum https://t.co/xnSdja17FZ

— Ola Westengen (@OlaWestengen) March 2, 2016

This from the project proposal:

…only 13% of farmers buy improved seed from formal markets in Uganda. The rest rely on seeds saved from the previous season or traded informally between neighbors, but such seeds generally produce far lower yields than genuine high yield hybrids… This problem can be addressed by empowering local seed businessmen or empowering the locals to produce their own seed through training.

So the “problem” is farmer-saved and -traded seed? That’s hardly addressing the havoc being wrought by Uganda’s seed counterfeiting gangs.

I’m all for helping farmers build their capacity in seed production, but there’s no reason why they should then produce nothing but “high yield hybrids.”

CCAFS tells the world how agriculture can adapt to climate change

The CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security has prepared syntheses papers on two of the topics related to agriculture that are being considered by UNFCCC’s Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) in 2016. The topics have incredibly unwieldy and confusing titles. They boil down, I think, to agricultural practices, technologies and institutions to enhance productivity and resilience sustainably, but you can read all the subordinate clauses in the CCAFS blog post which announces the publication of their reports.

Of course, what we want to know here is whether crop diversity is adequately highlighted among the said practices, technologies and institutions. The answer is, as ever, kinda sorta. The following is from the info note associated with the first paper, “Agricultural practices and technologies to enhance food security, resilience and productivity in a sustainable manner: Messages to the SBSTA 44 agriculture workshops.”

Crop-specific innovations complement other practices that aim to improve crop production under climate change, e.g. soil management, agroforestry, and water management. Crop-specific innovations include breeding of more resilient crop varieties, diversification and intensification.

Examples include the Drought Tolerant Maize for Africa initiative, disease- and heat-resistant chickpea varieties in India, improved Brachiaria in Brazil, hardy crossbreeds of native sheep and goats in Kenya, as well as changes in the crops being grown, such as moves from potato into organic quinoa, milk and cheese, trout, and vegetables in the Peruvian highlands.

The other paper, “Adaptation measures in agricultural systems: Messages to the SBSTA 44 Agriculture Workshops,” focuses on structures, processes and institutions. I particularly liked the emphasis on the importance on indigenous knowledge and extension systems. But why no mention of genebanks? Especially as Bioversity’s Seeds of Needs Project was nicely featured as a case study in the first paper. Here, after all is a concrete example of institutions — national and international genebanks — linking up to farmers to deliver crop diversity in the service of adaptation.

More access to the data on the Access to Seeds Index needed?

I took Jeremy’s advice and have been doing some digging around the excellent Access to Seeds Index website. So have a lot of other people, of course, to extract what’s relevant to their own particular obsession, 1 whether that be women farmers or small seed companies in Uganda or the informal seed sector. 2

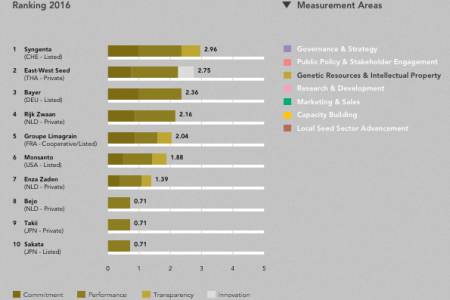

Our hobbyhorse here is agricultural biodiversity, of course, and thankfully one of the measurement areas addressed by the Index “seeks to capture how companies handle genetic resources and IP in ways that support the opportunities for smallholder farmer development.” The Index is calculated separately (for this and a further 6 measurement areas) for field crops, vegetables and companies active in East Africa. Here’s the ranking for the Genetic Resources & Intellectual Property measurement area as far as vegetables are concerned.

There are brief text summaries to go along with this ranking, as well as those for field crops and East Africa, but you have to do some jumping around on the website to get them, so I’ve taken the liberty of pooling them all together below:

Syngenta is the only company with a formal commitment not to pursue or enforce patents and applications in seeds or biotechnology in least-developed countries for private use by subsistence farmers. Companies provide access to their genetic resources. Monsanto, DuPont Pioneer, Dow AgroSciences and Bayer all collaborate with local partners to provide access to specific genetic material or biotechnology traits. This ranges from research on insect-resistant Bt cowpea and water-efficient maize. Support for public gene banks, important for the conservation and use of region-specific crop diversity, is common among global seed companies. But support for local gene banks in Index countries is largely overlooked. An exception for field crops is KWS, which supports public gene banks in Peru and Ethiopia… An exception among vegetable seed companies is East-West Seed, which supports gene banks in Indonesia and Thailand… Whereas global companies have formal commitments in place, most actual activities for the conservation and use of genetic diversity are found among regional companies. East African Seed, Kenya Seed Company and Seed Co, among others, partner with multiple local seed banks and global research institutes. NASECO and Kenya Seed Company also donate their germplasm to public research partners.

You have to refer to the appropriate bit of the methodology to fully understand all that, which means p. 54 of a 70-plus page report.

Unfortunately the methodology write-up is not much help unpacking that “[s]upport for public gene banks … is common among global seed companies,” which I found a bit problematic. The relevant bit of the methodology says:

C.II.2 Support for Public Gene Banks. The company supports– through monetary and/or in-kind contributions — public gene banks and/or global funds and initiatives serving public gene banks in Index countries.

I have a feeling this refers to international public genebanks, rather than national ones, but frankly either way I find it difficult to conceive how this could be described as “common” among seed companies. One wonders if the raw data will be made available for others to make their own determinations. Some objections are already surfacing, including this one from Oxfam quoted in The Guardian:

The EU and other countries have signed the international treaty on plant genetic resources for food and agriculture. It would be interesting if the index would in future score how companies comply with this treaty.

Although, to be fair, one way that companies contribute to the Treaty is in fact already covered by the Index

C.II.7 Benefit Sharing. The company contributes to the Benefit-sharing Fund created by the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

I would certainly love to see the raw data that went into calculating C.II.7 (and C.II.2 for that matter), as I cannot find anything on the website of the Treaty’s Benefit-Sharing Fund resembling a summary of the contributions made by companies.