Here is the panorama of the Banaue Rice Terraces from Chris's drone, 23 August 2015.

Posted by Gene Hettel on Tuesday, 25 August 2015

Brainfood: Citrus colours, Soil biodiversity portal, Bean genome, Food diversity & security, French landscape diversity, US pigs, Alien crops, Thai food retail

- Exploring the diversity in Citrus fruit colouration to decipher the relationship between plastid ultrastructure and carotenoid composition. New, weird plastids mean new, weird colours.

- Towards a global platform for linking soil biodiversity data. A DivSeek for soils?

- A reference genome for common bean and genome-wide analysis of dual domestications. Not sure how we missed this. Two domestications confirmed, with distinct genomic signatures.

- Variability of On-Farm Food Plant Diversity and Its Contribution to Food Security: A Case Study of Smallholder Farming Households in Western Kenya. No relationship between farm diversity and food security. Say what?

- What is the plant biodiversity in a cultural landscape? A comparative, multi-scale and interdisciplinary study in olive groves and vineyards (Mediterranean France). Low intensity management with an eye to heritage is good for diversity. But, given the above, so what?

- Relationships among and variation within rare breeds of swine. American pig breeds are real. Mostly.

- Alien Crop Resources and Underutilized Species for Food and Nutritional Security of India. Bring them on!

- Traditional, modern or mixed? Perspectives on social, economic, and health impacts of evolving food retail in Thailand. It would be a pity of fresh markets were to disappear.

Documenting improved variety adoption

In my defence, I have visited the ASTI website before. Just not in a while, unfortunately. And I therefore missed a lot of developments. So thank you, Jeremy, for sending me there again earlier today. But let’s step back a bit. What is ASTI, anyway?

Agricultural Science and Technology Indicators (ASTI) provides trusted open-source data on agricultural research systems across the developing world. Led by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), ASTI works with a large network of national collaborators to collect, compile, and disseminate information on financial, human, and institutional resources at both country and regional levels across government, higher education, nonprofit, and (where possible) private for-profit agricultural research agencies.

Very laudable. There’s a lot of useful stuff on the website, organized by country and region, but also covering the CGIAR centres. And the last is what I would like to focus on for a minute here. ASTI is hosting two projects tracking the adoption of improved varieties in South Asia and Africa. The raw data is downloadable, but there are useful summary graphics, though I would have liked them to be more easily sharable (the following examples are screenshots).

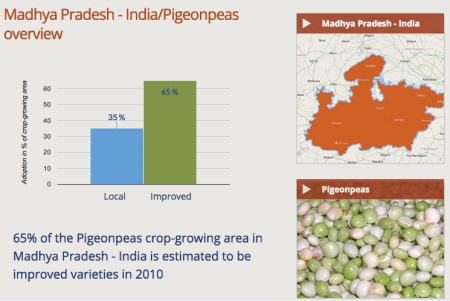

So, if we take as an example pigeonpeas in Madhya Pradesh, we get this overview:

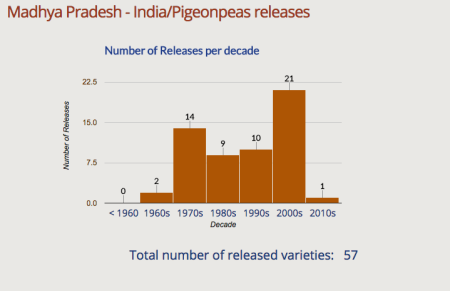

And a time line of releases:

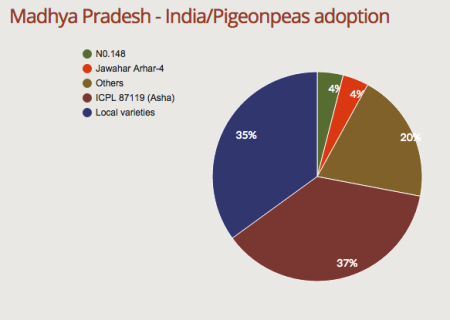

And, perhaps most interestingly, the level of adoption of the main varieties:

And if you’re interested in that 37% share, and I know you are, you can find out all about the variety in question, ICPL 87119 (otherwise known as Asha) from ICRISAT.

Evaluating evaluation networks

Mike Jackson, who ran the IRRI genebank 20 years ago, has some provocative things to say on his blog about the International Network for Genetic Evaluation of Rice (INGER), which has just turned 40. Here is Mike’s main point:

In my opinion, INGER could—and should—have been more. According to the riceTODAY article, INGER is today, 40 years after it was founded, at ‘the crossroads’. But it was already at a crossroads almost 25 years ago when it became clear that UNDP support would end. Opportunities were not seized then, I contend, to bring about radical and efficient changes to the management and operations of this important rice germplasm network, but without losing any of the benefits of the previous 20 years. I also believed it should be possible to add even more scientific value.

If I understand Mike correctly, he thinks INGER has gone for quantity (of trials) rather than quality of late, and missed out on some clear opportunities to be even more successful than it has been. Counterfactual history is always tricky, but I wonder whether this is a testable proposition. Maybe there’s a natural experiment out there? For example, are there countries that have not taken much advantage of INGER in the past couple of decades. How have their rice improvement efforts fared in comparison to countries which have?

Coincidentally, there was a short article in the Times of India recently trumpeting the release of rice varieties of low glycemic index. Can INGER take some of the credit for that, I wonder? Well, let’s have a look.

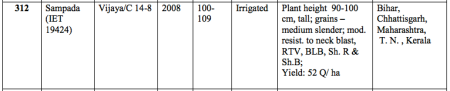

One of the varieties in question is Sampada. The Indian Directorate of Rice Development’s catalogue of released varieties (1996-2012) has the following entry for this variety:

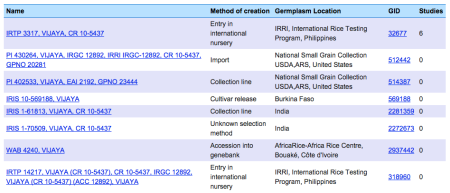

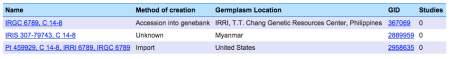

The immediate parents are therefore Vijaya and C 14-8. You can look these up in the International Rice Information System. Vijaya has featured in INGER’s nurseries:

And C 14-8 is safely in the IRRI genebank:

We saw it for wheat and maize, and now for rice. Partnership with the relevant CGIAR centre has been extremely important in the success of the Indian national breeding programmes for these crops.

Now, are there countries for which these partnership have not been so strong? And how successful have their breeding programmes been?

Brainfood: Brassica rethink, Camel colours, Parsing the ITPGRFA, Static buffalo, Traits not taxa, Expert tyranny, Chinese pollinators, Heritage landscapes, Mining text, Diversity & nutrition

- Domestication of Brassica oleracea L. It happened in the balmy Mediterranean, not along those blustery Atlantic cliffs.

- Validating local knowledge on camels: Colour phenotypes and genetic variation of dromedaries in the Nigeria-Niger corridor. The locally recognized colour-based breeds are not supported by the genetics.

- The Battle over Plant Genetic Resources: Interpreting the International Treaty for Plant Genetic Resources. The Treaty phrase “genetic parts and components, in the form received” can be interpreted in ways that do not clash with TRIPS. The author also suggests that the Benefit Sharing Fund should be used to pay lawyers, but I’m not sure if that’s tongue-in-cheek.

- The response of the distributions of Asian buffalo breeds in China to climate change over the past 50 years. Fancy maths says it’s minimal.

- Functional traits in agriculture: agrobiodiversity and ecosystem services. It’s not the taxa. Or it shouldn’t be.

- Expert opinion on extinction risk and climate change adaptation for biodiversity. In situ most preferable, ex situ most feasible.

- Conserving pollinator diversity and improving pollination services in agricultural landscapes.The view from China is much like the view from everywhere else.

- Heritage Values and Agricultural Landscapes: Towards a New Synthesis. Back to the future: heritage can mean resilience.

- Using legacy botanical literature as a source of phytogeographical data. Text parsed to yield maps. Brave new world.

- Production diversity and dietary diversity in smallholder farm households. Want better nutrition? Access to markets better than promoting production diversity.