We’re trying something new for us this week. Dr Geo Coppens co-authored an interesting paper 1 recently which brings together a number of our concerns: domestication, diversity, crop wild relatives, spatial analysis… He’s written quite a long piece about his research, which we’ll publish here in three instalments. This is the second instalment. Here’s the first, in case you missed it.

To investigate the origin of cultivated cotton in the New World, we also had to define the distribution of the wild precursors, which meant distinguishing True Wild Cotton (TWC) populations from feral (secondarily wild) populations. We first defined five categories: (1) TWC populations, which were described as such by cotton experts with consistent ecological and/or morphological criteria; (2) wild/feral cottons, reported to grow in protected areas and/or forming relatively dense populations in secondary vegetation; (3) feral plants living in anthropogenic habitats (field and road margins); (4) cultivated perennial cottons; and (5) plants of indeterminate status. We then organized our extensive dataset of locality information from herbaria and genebanks in the same way as Russian nesting dolls.

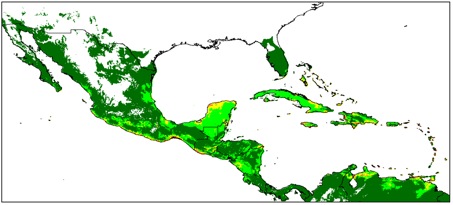

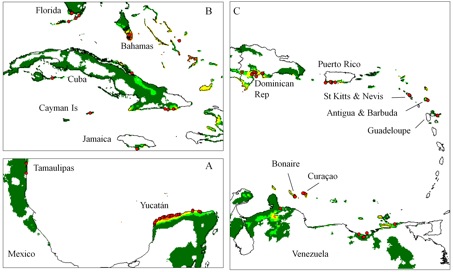

Avoiding the problematic comparisons between consecutive categories, we first modelled G. hirsutum distribution based on the whole sample, then reducing the sample to ‘feral’+‘wild/feral’ + TWC , then to ‘wild/feral’+TWC, and finally to TWC alone. Thus, we could see that the distribution model (we used the Maxent software for niche modelling) was not significantly affected by the successive removals of specimens classified as indeterminate, cultivated, or feral. Only the model based on TWC populations diverged very clearly, their distribution being severely restricted to a few coastal habitats, in northern Yucatán and in the Caribbean, from Venezuela to Florida (Figures 1 and 2).

A principal component analysis on climatic parameters confirmed the absence of clear differences among the climatic niches of cultivated, feral, and ‘wild/feral’ populations, contrasting strikingly with that of TWC populations, restricted to the most arid coastal environments. The TWC habitat’s harsh conditions are quite certainly related to the fact that “Gossypium is xerophytic and that even its most mesophytic members are intolerant of competition, particularly in the seedling stage” (Hutchinson, 1954). The proximity to the sea plays a role itself, for these “extreme outpost plants” (Sauer, 1967). Indeed, as Fryxell (1979) puts it, wild tetraploid cottons are strand plants adapted to mobile shorelines, with impermeable seeds adapted to salt water diffusion. The instability of their habitat “is in itself highly stable” and very ancient, so “that the pioneers are simultaneously old residents”.

Extrapolating this TWC climatic model to South America and Polynesia points towards places where other wild representatives of tetraploid Gossypium species have been reported, which gives a strong example of niche conservatism. Thus, the distribution model has perfectly captured those conditions that are related to both biotic and abiotic constraints for the development of TWC populations.

To be continued…