- Environmental context and herbivore traits mediate the strength of associational effects in a meta-analysis of crop diversity. More crops in fields means fewer pests, by and large.

- Approaches and Advantages of Increased Crop Genetic Diversity in the Fields. How they get more crops into fields in Nepal, and why it’s a good thing to do so.

- Agroecology as a transformative approach to tackle climatic, food, and ecosystemic crises. More crops in fields can be transformative.

- Agroecology Can Promote Climate Change Adaptation Outcomes Without Compromising Yield In Smallholder Systems. More crops (and other things, to be fair) in fields means better climate change adaptation.

- Providing targeted incentives for trees on farms: A transdisciplinary research methodology applied in Uganda and Peru. To get more tree crops in fields, follow the money.

- Impact of small farmers’ access to improved seeds and deforestation in DR Congo. Getting more, better crops into fields may lead to loss of primary forest if they don’t come with fertilizers.

- Small-scale farming in drylands: New models for resilient practices of millet and sorghum cultivation. Models show that plant growing cycle, soil water-holding capacity and soil nutrient availability determine how much sorghum and millets are in fields.

Brainfood: Domestication syndrome, Plasticity & domestication, Founder package, Rice domestication, Aussie wild rice, European beans, Old wine, Bronze Age drugs

- Phenotypic evolution of agricultural crops. Plants have evolved to become bigger, less able to run away, and more delicious to herbivores, and breeders can use insights into that domestication process to develop an ideotype for multipurpose crops adapted to sustainable agriculture.

- The taming of the weed: Developmental plasticity facilitated plant domestication. The authors made plants less lazy, more attractive, and easier to cook — all by simply hanging out with them for a season or two. And so did early farmers.

- Revisiting the concept of the ‘Neolithic Founder Crops’ in southwest Asia. The earliest farmers in the Fertile Crescent did not do the above for just a single, standard basket of 8 crops.

- The Fits and Starts of Indian Rice Domestication: How the Movement of Rice Across Northwest India Impacted Domestication Pathways and Agricultural Stories. Rice began to be cultivated in India in the Ganges valley, moved in a semi-cultivated state to the Indus, got fully domesticated there, then met Chinese rice. No word on what else was in the basket.

- Analysis of Domestication Loci in Wild Rice Populations. Australian populations of wild rice have never been anywhere near cultivated rice, but could easily be domesticated.

- Selection and adaptive introgression guided the complex evolutionary history of the European common bean. The first introductions were from the Andean genepool, but then there was introgression from that into the Mesoamerican, and both spread around Europe. A bit like Indian meeting Chinese rice?

- Ancient DNA from a lost Negev Highlands desert grape reveals a Late Antiquity wine lineage. One thousand year old grape pits from the southern Levant can be linked to a number of modern cultivars, which could therefore be adapted to drier, hotter conditions.

- Direct evidence of the use of multiple drugs in Bronze Age Menorca (Western Mediterranean) from human hair analysis. There was probably not a single package of drug plants either.

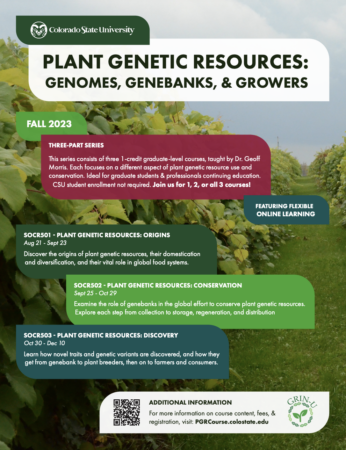

Genomes, Genebanks, and Growers… The Course

Your regular reminder that Colorado State University runs a great course entitled Plant Genetic Resources – Genomes, Genebanks, and Growers. And they’re now taking registrations for the Fall 2023 semester. Go for it. You won’t regret it.

Your regular reminder that Colorado State University runs a great course entitled Plant Genetic Resources – Genomes, Genebanks, and Growers. And they’re now taking registrations for the Fall 2023 semester. Go for it. You won’t regret it.

There are online training resources at GRIN-U, courtesy of the same project.

The case against biofortification

Wait, what? Against biofortification? What can possibly be the case against breeding staple crops to have higher concentrations of micronutrients? How can you argue against making wheat or beans more nutritious?

Well, in his latest Eat This Podcast episode, Jeremy interviews one of the authors of a paper which argues just that. And that author is…Jeremy:

…we focus on four things, really. One is about the yield. There seems to be a yield penalty. That is, you don’t get as much total crop from a biofortified food as you do get from a non biofortified variety. Another worry is genetic uniformity. A third is about their suitability for the very poor subsistence farmers who are probably the ones who most need more micronutrients in their diet. And finally, there’s almost no evidence that it actually works, that it actually improves the health and well being of the people who eat biofortified foods. In fact, it’s really strange to … It’s really difficult to find evidence that it works.

Maarten van Ginkel and Jeremy go on to say that a much better way to tackle micronutrient deficiencies — hidden hunger — is more diverse diets.

In fact, I think even uber-biofortificators such as HarvestPlus would probably concede that point, judging by an article they have just released marking their twentieth anniversary. Though I suspect that was not always the case.

Be that as it may, I think each of Maarten and Jeremy’s drawbacks of biofortification can be disputed, or indeed rectified, as they in fact concede, to be fair. For example, does a yield penalty actually matter everywhere? And has the release of a biofortified variety in an area actually led to a decrease in genetic diversity there? And if it has, could that not be addressed simply by more, and more diverse, biofortified varieties? And yes, the evidence that release of a biofortified variety translates into positive nutritional outcomes is limited and patchy — but not non-existent.

Anyway, the central fact remains that we still don’t know whether a more holistic approach to hidden hunger through diet diversification would have been more cost-effective and sustainable than the at least $500 million or so that Maarten and Jeremy say have gone into biofortification over the years.

LATER: Oh and BTW, there’s a Biofortification Hub.

Brainfood: Pollinator evolution, Pollinator diversity, Livestock, Yak milk consumption, Poultry in situ conservation, Soil stress, Self-domestication, Natural history collections

- The expansion of agriculture has shaped the recent evolutionary history of a specialized squash pollinator. The genetic diversity of an insect crop pollinator has been affected by the fact that it pollinates a crop.

- Native pollinators improve the quality and market value of common bean. The diversity of native insect crop pollinators affects the value of the crop they pollinate.

- A global approach for natural history museum collections. Basically amounts to “ask curators what they have.” Including presumably specimens of insect pollinators. We’ve been doing this for PGRFA for quite a while now, one way or another. Back to mainly plants next week, hopefully, but let’s keep going with animals for now, and let’s see what more we can learn.

- A 12% switch from monogastric to ruminant livestock production can reduce emissions and boost crop production for 525 million people. Ruminants are not all bad after all.

- Permafrost preservation reveals proteomic evidence for yak milk consumption in the 13th century. The Mongols thought this particular ruminant was just great.

- The self-management organization as a way for the in situ conservation of native poultry genetic resources. In response to the promotion of exotic commercial poultry breeds, women’s groups in Mexico have got together and developed rules to protect native hens. Please let not these be among the 12% of monogastrics that get replaced by yaks.

- Increasing the number of stressors reduces soil ecosystem services worldwide. It’s the number of different stressors, more than their aggregate strength, that most affects how badly soils are stressed. Goes for me too, to be honest.

- Elephants as an animal model for self-domestication. I’ll believe it when elephants domesticate yaks.