A nice evening yesterday listening to a great talk by Dr Ola Westengen of NordGen on the importance of global efforts to conserve crop diversity, and in particular the role of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. That was followed by a reception in a very pleasant space in the Mediterranean section of the botanic garden of the University of Bonn. But not before a tour of the economic plants collection, which is across the road from the main grounds of the botanic garden. Well worth a visit if you’re ever in Bonn. Perhaps unusually, this botanic garden has a long history of interest in the study and conservation of crop diversity. For example, Friedrich August Koernicke, who worked there in the middle of the 19th century, made a famous collection of local cereal landraces. A little genebank is being developed for long-term seed storage, which should be ready by the end of the summer.

A nice evening yesterday listening to a great talk by Dr Ola Westengen of NordGen on the importance of global efforts to conserve crop diversity, and in particular the role of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. That was followed by a reception in a very pleasant space in the Mediterranean section of the botanic garden of the University of Bonn. But not before a tour of the economic plants collection, which is across the road from the main grounds of the botanic garden. Well worth a visit if you’re ever in Bonn. Perhaps unusually, this botanic garden has a long history of interest in the study and conservation of crop diversity. For example, Friedrich August Koernicke, who worked there in the middle of the 19th century, made a famous collection of local cereal landraces. A little genebank is being developed for long-term seed storage, which should be ready by the end of the summer.

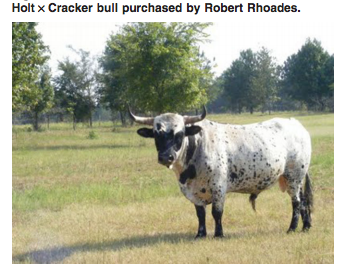

Robert Rhoades remembered

It was just over four years ago that Prof. Robert Rhoades, pioneer of agricultural anthropology, passed away. He’s remembered this month in a Special Issue of the journal Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment entitled Tending the Field.

Prof. Rhoades didn’t just invent the field of agricultural anthropology. Here’s an extract from one of the papers, Long in the Horn: An Agricultural Anthropology of Livestock Improvement, by Tad Brown, one of his students, on the conservation of the Pineywoods cattle landrace in the southern US:

Through my fieldwork, I also located one lone bull descending from a Holt cow in Alabama. It is the offspring of a cross with a Florida Cracker bull. After some deliberation, Rhoades bought that half-bred Holt bull, and he would jokingly threaten to start his own strain (see Figure 2). To Rhoades, a purebred landrace was a bit of a contradiction in terms. Just as cattlemen derived named-strains from the larger population of woods cattle, the division and recombination of family herds was the process by which people and cattle came to inhabit the southeastern pines. As such, the emphasis on genetics and purity of descent in livestock conservation efforts today can be somewhat averse to the social history from which the landrace breeds were derived (R. Rhoades, personal communication).

And here’s that Fig. 2. Prof. Rhoades practiced what he preached. How many of us can say that?

And here’s that Fig. 2. Prof. Rhoades practiced what he preached. How many of us can say that?

Brainfood: Old flax, Rice in Spain, Rice in Iran, Mozambican cowpea, Agrobiodiversity reserve, Old olives, Georgian livestock, Crowdsourcing fungi

- Harvesting wild flax in the Galilee, Israel and extracting fibers — bearing on Near Eastern plant domestication. The wild stuff was harvested before the Neolithic Revolution.

- Building resilience to water scarcity in southern Spain: a case study of rice farming in Doñana protected wetlands. Better to restore part of the rice fields to natural wetlands.

- Evaluation of rice dominance and its impact on crop diversity in north of Iran. Rice can’t catch a break in Iran either.

- Evaluation of four Mozambican cowpea landraces for drought tolerance. One of them is promising.

- Agro-Biodiversity Spatial Assessment and Genetic Reserve Delineation for the Pollino National Park (Italy). Somewhat gratuitous use of GIS, as far as I can see, but pretty maps.

- A comparative analysis of genetic variation in rootstocks and scions of old olive trees — a window into the history of olive cultivation practices and past genetic variation. Much more variation among rootstocks than scions.

- The diversity of local Georgian agricultural animals. I’d like to see a Megrelian horse one day, they sound cool.

- Crowdsourcing to create national repositories of microbial genetic resources: fungi as a model. Why just fungi, though?

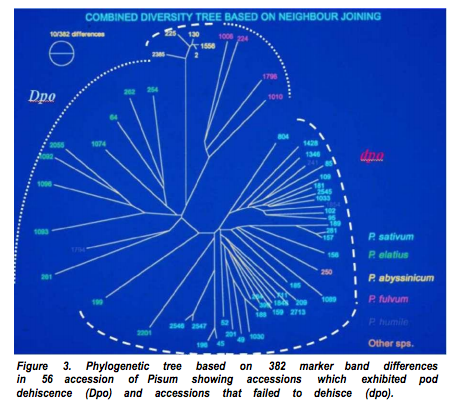

Pisum phylogeny illustrated in really cool way

Yeah, sure, you can publish your Pisum phylogenetic tree the usual way:

But isn’t it a whole lot better to do it like this?

That’s the author, Mike Ambrose of the John Innes Centre Germplasm Resources Unit showing off his handiwork. Thanks to Nora Castañeda for the photo. It’s all happening because of the PGRSecure conference in Cambridge, UK. which you can follow on Twitter.

LATER: And thanks to Jim Croft for pointing out something similar from Down Under.

Food policy ignores genebanks, so what else is new?

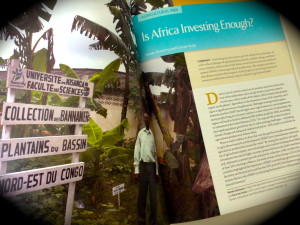

IFPRI’s latest Global Food Policy Report is out. I know because I was at the launch a couple of days ago in Berlin. Leafing through the hard copy while listening to IFPRI’s DG summarize the main findings, I was heartened to see the photo reproduced here, at the start of the section entitled “Is Africa investing enough?”. It’s a banana genebank! In a publication on food policy? Will wonders never cease?

IFPRI’s latest Global Food Policy Report is out. I know because I was at the launch a couple of days ago in Berlin. Leafing through the hard copy while listening to IFPRI’s DG summarize the main findings, I was heartened to see the photo reproduced here, at the start of the section entitled “Is Africa investing enough?”. It’s a banana genebank! In a publication on food policy? Will wonders never cease?

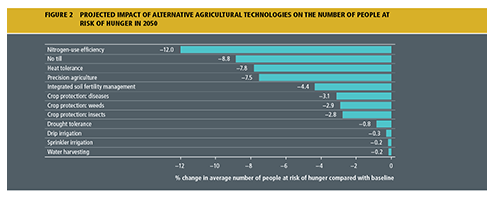

Unfortunately, they did. There’s nothing at all in the report about genebanks, apart from that photo. That’s despite the fact that another section, the one entitled “The promise of innovative farming practices,” did a great job of highlighting the importance of interventions that ultmately depend on the genetic diversity found in genebanks. IFPRI researchers used a geographically explicit modelling approach to predict the effect of 11 different agricultural technologies on yield, global harvested area and number of people at risk of hunger in 2050. They did this for three major staples: maize, rice and wheat.

It turned out that of the three breeding-based technologies included among the 11 — that is, new varieties that are more heat tolerant, N-efficient or drought-tolerant — the first two were consistently the ones resulting in the greatest impact. No-till agriculture was also up there. But really, if you were going to do just one thing to alleviate hunger, breeding for N-efficiency would probably be it, according to this analysis.

So why not mention the source of the raw materials for doing that? Especially as IFPRI’s fellow CGIAR centres manage global germplasm collections of these crops which have been formally recognized as fundamentally important to food security (check out Article 15 of the International Treaty for Food and Agriculture). It’s amazing how no opportunity is ever wasted of taking genebanks for granted.