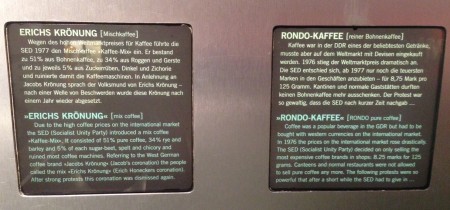

Many thanks to my colleague Amanda Dobson for this photo (click to embiggen) from the DDR Museum in Berlin. Sometimes one prefers a little less agricultural biodiversity in one’s food — and beverages — doesn’t one?

A cassava for the ages in Hawaii

Probably the biggest cassava you’ve ever seen, weighing in at about 80 kg. No word on what variety it is, alas, nor how long it was in the ground for.

Featured: Potato taxonomy

Roel Hoekstra reacts to our suggestion that CGN may want to consider changing the taxonomic determination of a potato accession in its genebank:

In general gene banks should be conservative in renaming accessions and not follow the latest publication, unless there is a clear misclassification … The suggestion on this Weblog, that CGN should rename accessions CGN18108 (from ARG) into S. venturii should probably include all okadae’s from ARG. However, taxonomy is a sensitive issue. So far, CGN was reluctant to rename okadae accessions, in particular as long as Sturgeon Bay does not rename them. Too much renaming may confuse/annoy the users of the germplasm. The discussion on this Weblog at least triggers to take a look into the available data again. Personally, I would not be surprised to once find these two species reunited again.

That ellipsis stands for a pretty lucid summary of the nomenclatural history of the two species involved, very much worth reading in full. Thoughts?

The slippery politics of agricultural biodiversity

It happens sometimes. You see a bunch of apparently random, unrelated things, and then after a while suddenly it hits you that there’s a thread of sorts running through them after all. It’s a trick of the mind, of course, but still. Take my reading these past few days. It included a review of an old exhibition on the historical links between Venice and the Orient (an interest of mine), a newspaper article on the latest developments on Cyprus (an old stamping ground of mine) and a paper from the International Institute of Social Studies on food sovereignty (homework). I suppose I should not have been surprised, but the nexus of agrobiodiversity (and its products) and politics turned out to be a point of connection among these, if maybe not an actual thread. Here’s how.

Venice and the Islamic World, 828–1797 was the title of an exhibition held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York in 2007. There was a review of it at the time in the NY Review of Books, which I ran into at the weekend while binge-reading William Dalrymple stuff. Among many great observations, there was this little gem on the diplomatic missions between Venice and Egypt:

The emissaries would have been carrying large numbers of Parmesan cheeses, apparently the diplomatic gifts most eagerly favored by appreciative sixteenth-century Mamluk governors.

I don’t know what it was, maybe the slightly surreal image of a Venetian trireme being unloaded at some slippery Nilotic dock, the sweaty Parmesan wheels hoisted laboriously onto richly baldaquined camels as turbaned dragomans look on, but the sentence stuck with me. 1 And so did the following, this morning, while scanning a piece in the International Herald Tribune on the latest, hopeful signs from the tragically divided island of Cyprus. I spent several years there back in the 90s, and I try to stay informed:

In 2010, the community planted a Peace Park, an oasis with 1,100 carob trees and a playground. Soon after, the group restored a dilapidated Frankish cloister abutting the church, less than 500 feet from a Turkish mosque towering in the sun.

See, there it is again, agrobiodiversity helping out with politics.

Ah, but wait. I really should not be calling it that at all, should I. Because, according to Patrick Mulvany in a footnote in the paper Food Sovereignty: A Critical Dialogue, which you may remember we nibbled last week:

The term Agricultural Biodiversity is, in the English language, the accepted term in the United Nations FAO and CBD and by many authors that come from a public interest perspective. It is also a useful term in that it highlights the ‘cultural’ dimension. The reductionist term ‘agrobiodiversity’, though common in translation in other languages (and translation from those languages), is sometimes used by institutions and individuals who consider agricultural biodiversity mainly as an exploitable resource.

And there I was thinking that “agricultural biodiversity” and “agrobiodiversity” were completely interchangeable terms. How naive of me. Don’t you just love agricultural biodiversity? There’s politics even in what you call it.

Brainfood: Weird coconut, Rainforest management, Pollinators and grazing, Pre-Mendel, Italian grapes, Indian fibre species, Cereal relatives, Brazil nut silviculture

- Scope of novel and rare bulbiferous coconut palms (Cocos nucifera L.). Produces bulbils instead of floral parts.

- Holocene landscape intervention and plant food production strategies in island and mainland Southeast Asia. Like the Amazon.

- Grazing alters insect visitation networks and plant mating systems. More outcrossing in grazed birch woods.

- Imre Festetics and the Sheep Breeders’ Society of Moravia: Mendel’s Forgotten “Research Network.” Before peas, there were sheep.

- Genetic Characterization of Grape Cultivars from Apulia (Southern Italy) and Synonymies in Other Mediterranean Regions. About half are also grown somewhere else.

- Fibre-yielding plant resources of Odisha and traditional fibre preparation knowledge − An overview. 146 species, no less.

- Functional Traits Differ between Cereal Crop Progenitors and Other Wild Grasses Gathered in the Neolithic Fertile Crescent. How do cereal progenitors differ from all the other grasses our ancestors used to eat? Adaptation to competition and disturbance. They were weeds, basically.

- Testing a silvicultural recommendation: Brazil nut responses 10 years after liana cutting. Biodiversity bad for Brazil nuts.