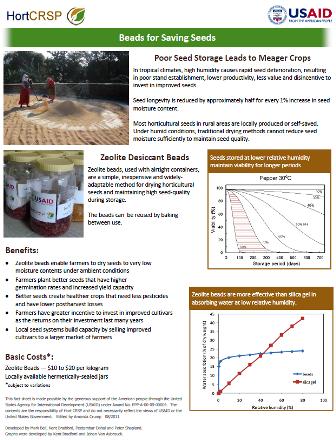

The Horticulture Collaborative Research Support Program at UCDavis has a nice factsheet out about Zeolite Desiccant Beads. Why?

The Horticulture Collaborative Research Support Program at UCDavis has a nice factsheet out about Zeolite Desiccant Beads. Why?

Zeolite beads, used with airtight containers, are a simple, inexpensive and widely adaptable method for drying horticultural seeds and maintaining high seed‐quality during storage. The beads can be reused by baking between use.

And of course we know that’s important:

In tropical climates, high humidity causes rapid seed deterioration, resulting in poor stand establishment, lower productivity, less value and disincentive to invest in improved seeds.

Although farmers seem to be the clients here, I thought perhaps this might be a good, relatively low-cost solution for genebanks too, so I ran the factsheet past some seed experts at Kew and IRRI. Thanks to both of them for allowing me to quote them.

It turned out that Fiona Hay, formerly at the Millennium Seed Bank at Kew and now at IRRI, has had quite a lot of experience with zeolite.

Indeed, we have done some work on these zeolite (=molecular sieve) drying beads on rice … in collaboration with the company, Rhino Research, in Thailand that is marketing them (and holds the patent — I’m not sure in which countries). See attachment..

Yes, they are a good desiccator, my concerns are that they could be too good and that they don’t appear to work as described — they don’t take up the same amount of water from the seeds as they do when they are placed over water. This means that is isn’t obvious how to calculate the right quantity of beads to use to dry seeds to a required moisture content. This is based on our work on rice (three different fresh seed lots), but seems to be at odds with what Kent Bradford (UC-Davis) has found for horticultural crops.

In terms of their use by farmers — I don’t think this technology is what they need. If the HORTCRSP project helps them to understand the need to dry seeds, OK; but there may be cheaper, simpler options.

They could be of more use in a genebank situation — once we know how to use them optimally. We are doing more work on this. One of Rhino’s latest products using the beads are bins containing a core of beads which is in contact with some indicating silica gel. Seeds are put in the bin and the silica is used to know when to regenerate the beads. This could be useful for genebanks without proper drying and/or storage facilities. I’d like to get hold of a couple of these to try them out.

Robin Probert at the Millennium Seed Bank then added:

What annoys me most about the USAID fact sheet promotion of Zeolite beads is that it brags the value of Zeolite beads over silica gel for small farmers drying seeds for sowing. We have known for decades that the problem facing local farmers is the rapid loss in viability that can occur if seeds remain at high ambient relative humidity combined with warm temperatures. We also know that if farmers were able to dry seeds from say 80% equilibrium relative humidity (eRH) to below 50% eRH, seed longevity would be improved by several fold. This could mean the difference between seeds surviving for only a few months to a few years.

The fact sheet boldly states (with a nice graph to make the point) that ‘Zeolite beads are more effective than silica gel in absorbing water at low relative humidity’. But this could be written another way: ‘silica gel is more effective than Zeolite beads in absorbing water at high humidities’. Fiona’s work published in Seed Science and Technology last year [Fig 5 in Hay et al (2012) SS&T 40, 374-395] elegantly confirms this.

What this means is that a farmer would need less silica gel than Zeolite beads to dry seeds from ambient humidity to a safe moisture content for short-medium term storage (≤ 50% eRH). But what about cost? The USAID leaflet states that Zeolite beads can be bought for 10-20 US $ per Kg. We buy silica gel beads that we use in our drying drums designed for small-scale seed drying for less than 10 US $ a Kg.

Using Zeolite beads to dry seeds down to very low moisture contents for long-term storage is a different matter and as Fiona’s paper demonstrates, Zeolite beads may have it over silica gel for this purpose. However, as the paper also points out, calculating the weight of Zeolite beads needed is not straightforward and compared to silica gel there is a much greater risk of over drying.

All in all, I know where my money is.

So it turns out that, on balance, according to these experts at any rate, the Zeolite beads may actually be more promising as a solution for resource-strapped genebanks around the world than for seed-saving farmers in the humid tropics. Which was, however, presumably not the aim of the USAID-supported project that came up with that factsheet. But let me tweet this to HortCRSP and see what they say. Stay tuned…