- SSR analysis of introgression of drought tolerance from the genome of Hordeum spontaneum into cultivated barley (Hordeum vulgare ssp vulgare). Scary thing is that only two wild accessions are involved.

- Transgenic Biofortification of the Starchy Staple Cassava (Manihot esculenta) Generates a Novel Sink for Protein. Fancy biotech puts more of a substance in cassava that nobody eats cassava for. No, wait.

- Whole genome duplication in a threatened grassland plant and the efficacy of seed transfer zones. Mixing of seed from different populations can be a good idea for conservation of rare plants, but not when they also differ in ploidy.

- Genetic diversity in widespread species is not congruent with species richness in alpine plant communities. Cannot use one as a proxy for the other.

Desperately seeking data

We’re trying something new here, trying to keep on the cutting edge of the inter webs.

What happened was, a couple of days ago, we saw a video about a warning service for UK growers of winter oilseed rape (aka canola). There’s a model that predicts when fungus outbreaks are particularly likely, so farmers don’t have to spray with fungicide on a schedule, rather than when most needed.

That’s good. But, just out of interest, I wondered how much diversity there is in the resistance to the two prime fungal threats among the varieties of oilseed rape grown in the UK. Because, maybe, farmers and researchers there could even consider whether sowing a mixture might give them as much protection as a fungicide. Just a thought, y’know.

What followed (curated and enlivened thanks to Luigi’s efforts) was https://wtcampaigns.wordpress.com/2012/10/30/ash-dieback-chalara/, and not in a particularly good way. 1

Bottom line: there is actually a lot of data at the HGCA, but it is in PDFs, which makes it harder to do any sort of analysis, and I couldn’t find anything on the area planted to specific varieties. Oh, and the email trail went cold very quickly.

When did groundnuts become perennials?

Dear IFPRI

Have you managed to turn groundnuts (Arachis hypogea) into a perennial? Or are you confused perhaps by the difference between perennials and nitrogen-fixing legumes, some of which are indeed perennial?

Your pals

Agro.agro.biodiver.se

P.S. Linking to an article behind a paywall doesn’t make a huge amount of sense either.

A chilli farmer spills the beans

Bioversity International has released a video featuring Esaú Hidalgo del Águila, 2010 winner of the Aji de Plata (Silver Chilli) for his chilli diversity.

This is part of a project to supply a growing demand in markets for new and different chilli flavours.

Safeguarding safflower

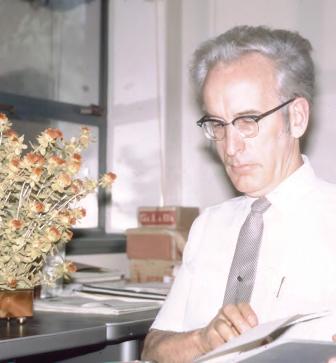

In the late 1950’s and mid 1960’s, Knowles traveled over 32,000 miles with his wife and son overland across North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia gathering germplasm of wild and domesticated safflower species, an effort which produced most of the species now in the USDA world safflower collection.

Paulden F. Knowles worked at UC Davis for 35 years, retiring in 1982. Just before he died in 1990, he wrote out in longhand the story of his career in safflower development. That document has now been edited Patrick E. McGuire, Ardeshir B. Damania, and Calvin O. Qualset of the Department of Plant Sciences, and is available online. It makes for fascinating reading. But I can’t resist the temptation of leaving you with an excerpt from the editors’ summary, rather than the report itself.

Paulden F. Knowles worked at UC Davis for 35 years, retiring in 1982. Just before he died in 1990, he wrote out in longhand the story of his career in safflower development. That document has now been edited Patrick E. McGuire, Ardeshir B. Damania, and Calvin O. Qualset of the Department of Plant Sciences, and is available online. It makes for fascinating reading. But I can’t resist the temptation of leaving you with an excerpt from the editors’ summary, rather than the report itself.

Paul Knowles’ work finished with the decade of the 1980s. At the time of his death in 1990, work was underway that would culminate with the opening for signature in 1992 of the Convention on Biological Diversity and its subsequent entry into force at the end of 1993. It is an important question whether he could have done his work in the international germplasm access and exchange environment that exists post-CBD. Certainly under the CBD, there is nothing in theory that would prevent his accomplishments, but in practice the many bilateral agreements for exchange of germplasm necessary today and the difficulty in obtaining these (as exemplified by the records of the past 20 years) make it highly unlikely that the current state of safflower knowledge and productivity would have been possible. The International Treaty for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture and its Multilateral System for genetic resources access that emerged in the early 2000s would not have helped Knowles’ safflower work either. Safflower is not one of the crops covered under the Treaty.