Thanks everyone for the inspiration for us to showcase the importance of the genetic diversity of rice via the story behind the origin of the rice variety Kasalath.

You’re welcome, IRRI. And I’m sure Abed Chaudhury would join us in that.

Agrobiodiversity is crops, livestock, foodways, microbes, pollinators, wild relatives …

David Duthie at UNEP runs a very useful mailing list called Bioplan aimed at, well, biodiversity conservation planners. He’s great at highlighting connections between different news items or scientific papers, and providing pithy summaries of the latest thinking in different areas. That was the case in a recent post on “how a growing body of researchers are beginning to sort … signal from noise” in the geographic responses of species to climate change, “and shape adaptive management strategies that MAY prevent the worst from happening.” Unfortunately, there is no online archive that I can link to, so I’ll just have to cut and paste from his email. Here it is:

1. Yes, they really are ALL moving:

Massachusetts Butterflies Move North as Climate Warms

reporting on:

G.A. Breed. (early online) Climate-driven changes in northeastern US butterfly communities. Nature Climate Change; DOI: 10.1038/nclimate1663 (open access; 4MB PDF)

2. And not all in the same way:

Studies Shed Light On Why Species Stay or Go in Response to Climate Change

reporting on:

Morgan W. Tingley, Michelle S. Koo, Craig Moritz, Andrew C. Rush, Steven R. Beissinger. The push and pull of climate change causes heterogeneous shifts in avian elevational ranges. Global Change Biology, 2012; DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02784.x (subscription required)

T. L. Morelli, A. B. Smith, C. R. Kastely, I. Mastroserio, C. Moritz, S. R. Beissinger. Anthropogenic refugia ameliorate the severe climate-related decline of a montane mammal along its trailing edge. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2012; DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1301 (open access)

3. But existing protected areas can act as “stepping stones” for species on the move:

Protected Areas Allow Wildlife to Spread in Response to Climate Change, Citizen Scientists Reveal

reporting on:

Thomas, C. D. (early online) Protected areas facilitate species’ range expansions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1210251109 (subscription required)

4. And new approaches to systemic conservation planning can build more resilience around existing protected area systems:

C.R. Groves et al. (2012) Incorporating climate change into systematic conservation planning. Biodiversity and Conservation, 2012 vol. 21(7) pp. 1651-1671 (open access)

The principles of systematic conservation planning are now widely used by governments and non-government organizations alike to develop biodiversity conservation plans for countries, states, regions, and ecoregions. Many of the species and ecosystems these plans were designed to conserve are now being affected by climate change, and there is a critical need to incorporate new and complementary approaches into these plans that will aid species and ecosystems in adjusting to potential climate change impacts. We propose five approaches to climate change adaptation that can be integrated into existing or new biodiversity conservation plans: (1) conserving the geophysical stage, (2) protecting climatic refugia, (3) enhancing regional connectivity, (4) sustaining ecosystem process and function, and (5) capitalizing on opportunities emerging in response to climate change. We discuss both key assumptions behind each approach and the trade-offs involved in using the approach for conservation planning. We also summarize additional data beyond those typically used in systematic conservation plans required to implement these approaches. A major strength of these approaches is that they are largely robust to the uncertainty in how climate impacts may manifest in any given region.

Craig Groves, a stalwart of The Nature Conservancy, AND a BIOPLANNER, co-authored “Designing a Geography of Hope: A Practitioner’s Handbook to Ecoregional Conservation Planning.” (open access)

I just love that phrase: “Designing a Geography of Hope”!

So do I.

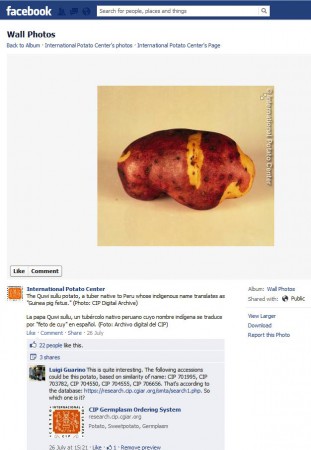

The International Potato Center has been running an Andean Potato of the Day feature on Facebook. And yes, they are potatoes, stop sniggering at the back there. Anyway, they’re really professional photos of often very weird and attractive traditional potato varieties, many of them with extremely weird names, and it made me curious as to what extent all this diversity is in CIP’s genebank. It turns out the photos were taken in 1999-2000 during a field trip into the Andes organized to provide high quality illustrations for the book “La Papa: Tesoro de los Andes.” CIP’s genebank curators were asked to help with the spelling and translation of the local names, but the photographs are of material freshly harvested from farmers’ fields, not the genebank. Most (not all, alas) of the varieties illustrated are in fact in the genebank, as you can check by searching for the local name (as I did for the “Quwi sullu” potato shown here), though it is occasionally tricky to be certain, due to variation in the spelling of the local name. This is another version of the problem we encountered in an earlier post dealing with rice, where it was not possible to be sure of the identity of material used in a particular piece of research because only the local name was quoted, rather than the accession number. Anyway, I bring all this up now because CIP has just announced the publication of an illustrated catalog of new potato varieties for Peru, with the now obligatory shout-out on Facebook. I haven’t seen the catalog yet, but I do hope it includes accession numbers.

The International Potato Center has been running an Andean Potato of the Day feature on Facebook. And yes, they are potatoes, stop sniggering at the back there. Anyway, they’re really professional photos of often very weird and attractive traditional potato varieties, many of them with extremely weird names, and it made me curious as to what extent all this diversity is in CIP’s genebank. It turns out the photos were taken in 1999-2000 during a field trip into the Andes organized to provide high quality illustrations for the book “La Papa: Tesoro de los Andes.” CIP’s genebank curators were asked to help with the spelling and translation of the local names, but the photographs are of material freshly harvested from farmers’ fields, not the genebank. Most (not all, alas) of the varieties illustrated are in fact in the genebank, as you can check by searching for the local name (as I did for the “Quwi sullu” potato shown here), though it is occasionally tricky to be certain, due to variation in the spelling of the local name. This is another version of the problem we encountered in an earlier post dealing with rice, where it was not possible to be sure of the identity of material used in a particular piece of research because only the local name was quoted, rather than the accession number. Anyway, I bring all this up now because CIP has just announced the publication of an illustrated catalog of new potato varieties for Peru, with the now obligatory shout-out on Facebook. I haven’t seen the catalog yet, but I do hope it includes accession numbers.

Dr Sigrid Heuer of IRRI, the lead author of the rice paper we blogged about a few days back, and which elicited quite some discussion as regards the country of origin of the material identified as having high P use efficiency, has just contributed a long comment.

Thank you very much for the lively discussion on our paper and the origin of Kasalath. I learned a lot in the process and will follow up on this by genotyping the different Kasalath accessions that we have at IRRI and will also ask BRRI to do the same for accessions from Bangladesh.

As you may know from our previous publications on Pup1 (Chin et al 2011 Plant Physiol 156: 1202–1216; Chin et al 2010 Theor Appl Genet 120(6): 1073–1086), we find the tolerant Pup1 haplotype in many stress-adapted varieties of various origins and also in IRRI breeding lines developed for rainfed environments. We mention this in the paper. Whether the Pup1 locus/PSTOL1 has the same origin in all these accessions and whether the gene that we cloned from the one specific Kasalath sample is the “original” gene is not known and might be difficult to determine.

Do read the whole thing. Our thanks to Dr Heuer for taking the time to respond, and for following-up some of the suggestions arising from the discussion.

We have often pointed out on this blog that it would be advisable to collect and stick into genebanks the local varieties found in a particular locality, 1 especially the ones found only at that locality, before introducing new diversity, no matter how much “better” that new diversity might be considered to be just now. In fact, I kind of made that point just a couple of days ago for sweet potato. So it is gratifying to find an example of just that, and nevermind that it’s from the livestock world.

The story is from an article by Dr Harvey Blackburn in the July issue of Hoard’s Dairyman. It’s kind of difficult to access online, but Corey Geiger, Assistant Managing Editor at Hoard’s, kindly allowed us to publish some excerpts. Dr Blackburn is coordinator of the USDA’s National Animal Germplasm Program (NAGP), based at the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation in Ft. Collins, Colorado. His article is entitled “Isolated Jersey genetics are a treasure trove” and tells the story of how the Royal Jersey Agriculture and Horticultural Society entered into a partnership with NAGP to safegueard the genetic integrity of the Jersey cattle breed.

Jersey dairy cattle are found in at least 82 countries where they have made substantial contributions to animal agriculture. The progenitors of these cattle can still be found on Jersey Island. For over 219 years these cattle have been kept in genetic isolation from non-Jersey Island cattle — but this situation changed in 2008. The Royal Jersey Agriculture and Horticultural Society (RJA&HS) promoted and after evaluation by the States of Jersey parliament concluded that Jersey genetics could be imported and used on island Jersey cattle, with a proviso that they have an enhanced pedigree status of seven generations of recorded ancestry and no known other breed in the pedigree.

But that wasn’t the only proviso.

An important consideration in allowing the importation of Jersey genetics was the need to have semen safely cryopreserved and stored in a secure facility. By having such a reserve the RJA&HS could reintroduce the pre-importation genetic composition of Jersey cattle, if so desired. The RJA&HS found a secure facility and willing partner with the National Animal Germplasm Program (NAGP) located at the National Center for Genetic Resources Preservation in Ft. Collins, Colorado and part of USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. The NAGP has been developing germplasm collections for all livestock species for over 10 years and has amassed over 700,000 samples from more than 17,000 animals representing approximately 130 livestock breeds and over 100 commercial and research lines. Currently the collection has over 600 bulls from U. S. and Canadian Jersey populations. The program has also been used by researchers and industry alike to characterize and reestablish animal populations.

Samples from 400 Jersey bulls were sent in January 2012.

The States of Jersey and RJA&HS decision to allow importation while ensuring pre-importation genetics was safely preserved provides a model for how genetic variability can be preserved while enabling the livestock sector to make necessary changes to meet existing and future production challenges. In addition it is an example of how countries can be mutually supportive in conserving animal genetic resources through gene banking.

Amen to that.