There seems — inevitably — to be something of a competition out there to produce maps of changes in climatic suitability for different crops. And I’m not saying that’s necessarily a bad thing. The recent launch of FAO’s GAEZ Data Portal gives us a much-needed alternative to the all-but-unusable offering by CCAFS. Sad to say, it is not much of an alternative.

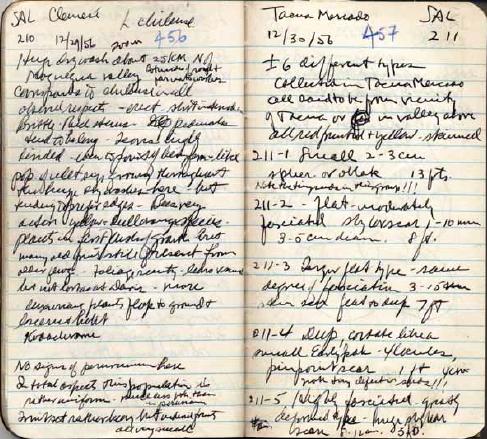

Here’s the quick version. CCAFS’s Adaptation and Mitigation Knowledge Network allows you to map current suitability, future suitability and change in suitability for a few crops. The example below is change of suitability for Phaseolus beans in Africa. I wasn’t able to get rid of those extraneous place markers, nor to export the results other than by screengrab, nor to import my own data to super-impose, nor to include the legend in any sensible way.

FAO tries to fill the gaping hole left by this well-meaning but flawed tool by providing something that: has menus which are extremely cumbersome to navigate; does not include change in suitability, but then doesn’t let you combine present and future suitability to do your own analysis; does allow you to choose different climate models, but again not to combine the results; does allow various download options, none of them particularly useful, and then only if you register; and, needless to say, doesn’t allow you to import data.

It’s hard to say how one could better replicate, and in fact accentuate, the bad features of one tool, while ignoring whatever good things it had. Frankly, I’m running out of patience with websites which are clearly designed by one set of geeks for another set of geeks. Meanwhile, users — you know, the people for whom this stuff is allegedly produced — are left to cry over their keyboards, and think of what might have been. And regret the fact that they’ll never get back the hour they’ve just wasted.