Good news for lovers of Mesoamerican crop wild relatives. Ten years in the making, the Atlas of Guatemalan Crop Wild Relatives (Atlas Guatemalteco de Parientes Silvestres de las Plantas Cultivadas) is finally out. 1

The Atlas provides detailed information on 105 species or subspecies of wild Guatemalan plants that are related to crops, including their description, distribution, diversity and conservation status. The species are organized into genepools corresponding to the 29 crops that were chosen for this study because of their economic, cultural and biological importance. Through an interactive Google Earth® interface, users of the Atlas can consult individual maps for each of the 105 plants included in the study, showing their known distribution based on the locations where scientific specimens were collected and projections of their potential range based on climate. Additional maps display areas of high species richness and diversity to assist conservation efforts. The maps draw upon a database of 2,600 records of scientific specimens conserved in numerous national and international institutions, primarily herbaria and seed banks.

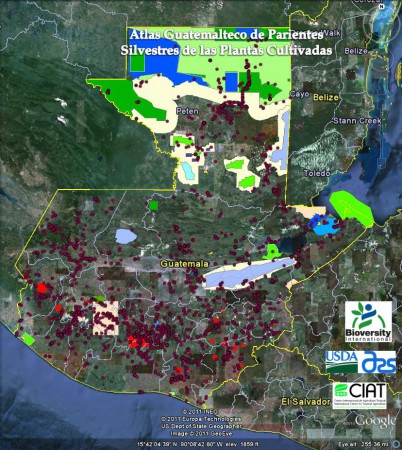

I’ve been playing around with it and it is pretty easy to use. Once you open the database in Google Earth 2 you can map the actual and potential distributions of individual species within each of the genepools, and also of the genepool as a whole. This, for example, is what you get for Phaseolus.

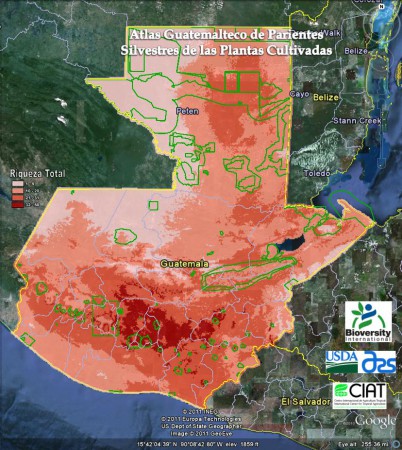

The green-to-red colouring shows the geographic distribution of species richness within the genus. One could quibble on aesthetic grounds about the choice of icon in this case, but that can always be changed by fiddling with the properties of the appropriate layer in Google Earth. More important is that the potential distributions and richness maps are clipped to the borders of Guatemala. I can understand the logic for that, an unwillingness to extrapolate, but I would perhaps have taken the risk, if only to stimulate neighbouring countries to embark on similar efforts.

The Atlas also allows you to look at the distribution of specimens and species richness in the dataset as a whole, and helpfully provides a layer on the protected areas of Guatemala. So this is all the specimens that the authors looked at, mapped together with the extents of national parks, archaeological sites and the like.

Just a little more fiddling with the properties of the layers allows you to see to what extent areas high in richness of crop wild relative species can be found within the confines of protected areas. The answer? Not much.

I don’t know enough about the flora of the region to be sure whether all the relevant species have been included, but the coverage looks pretty comprehensive to me. Clicking on the specimen icons gives you useful basic metadata. In some cases, the specimens are distinguished as to whether they are from herbaria and/or genebanks. So in this case the red dots are germplasm and the rings herbarium specimens of Phaseolus coccineus, which allows a rudimentary form of gap analysis, I suppose.

Perhaps more effort could have been expended in this direction. For example, are there really no wild Guatemalan cacao accessions conserved in genebanks around the world? And could not a little widget have been concocted to very roughly delimit gappy-looking areas? But that is to quibble, and no doubt both data and functionality could be added in the future. An English translation certainly will be. This will prove a marvellous conservation resource. Congratulations to the authors. 3 Now, guys, what about Paraguay?

Unfortunately, on the version I found the names of the varieties, which I take to be somewhere within the escutcheon at the bottom of the painting, are illegible. Having looked at all the bunches hanging there, that’s the only one that does seem vaguely horn shaped. The original is in the Villa Medicea in Poggio a Caiano, about 15 km northwest of Florence, and if I’m ever in the area I’ll try and get a better look. Old paintings and manuscripts are clearly a good source of information for modern-day fans of diversity sleuthing, although I confess I rely on others more expert than me to do most of the legwork. A perfect example is Andrea Borracelli,

Unfortunately, on the version I found the names of the varieties, which I take to be somewhere within the escutcheon at the bottom of the painting, are illegible. Having looked at all the bunches hanging there, that’s the only one that does seem vaguely horn shaped. The original is in the Villa Medicea in Poggio a Caiano, about 15 km northwest of Florence, and if I’m ever in the area I’ll try and get a better look. Old paintings and manuscripts are clearly a good source of information for modern-day fans of diversity sleuthing, although I confess I rely on others more expert than me to do most of the legwork. A perfect example is Andrea Borracelli,