More bad news from Thailand. After the worst floods in 50 years, the Chai Nat Research Centre has been under water for the past couple of months. That’s where a lot of the germplasm multiplication and regeneration work is done. In fact, it seems there were newly harvested seeds ready for storage when the floods came. Should any seeds make it to the national genebank at Pathum Thani near Bangkok, however, they would not be all that safe either. The area is under threat as the floodwaters makes their way south. That’s why the recommendation is for safety duplication of all accessions, preferably on another continent. And of course at Svalbard. Stay tuned for news as we get it. And very best of luck to all at the genebank.

New uses for meat and veg

Do play with your food. It could make you rich and famous, as it has English photographer Carl Warner. There’s a slideshow at La Repubblica, where the interview breathlessly gushes that “The Arcimbolo of the new millennium is sexy, speaks English, and uses his art to fight against obesity”. We’ve seen some edible landscapes before; I’m linking to these partly because Warner has used some very unusual species in his images. I’m sure you’ll be able to find them …

Solving broomcorn millet

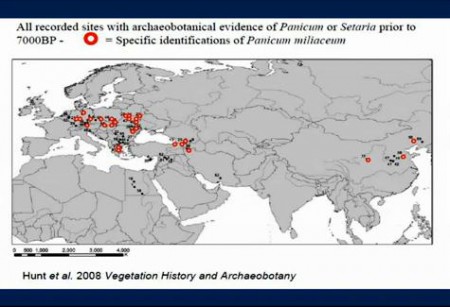

![]() Broomcorn millet is a bit of a puzzle. You start to get archaeobotanical evidence for cultivated Panicum miliaceum in both China and Europe at about the same time before 7000 BP.

Broomcorn millet is a bit of a puzzle. You start to get archaeobotanical evidence for cultivated Panicum miliaceum in both China and Europe at about the same time before 7000 BP.

Independent domestication or transmission along the fabled Silk Road (like wheat)? And if the latter, in which direction? You can hear the conundrum set out in more eloquent terms by the eminent archaeologist Prof. Colin Renfrew in this talk from last March, from which I’ve nicked the figure. You can just go to about 20 minutes in. But do yourself a favour and watch the whole thing.

Anyway, Prof. Renfrew mentions that genetic work is underway on Panicum which promises eventually to clarify the situation. And here it is. And, alas, interesting as it is, it doesn’t, not much. The paper in Molecular Ecology by Harriet Hunt and others looks at new microsatellite data on 98 landraces from across Eurasia obtained from genebanks in Russia, the US and Japan, and from new fieldwork in Inner Mongolia. 1

The researchers find evidence for two largely distinct genetic clusters, or genepools, one centered on China and one in Europe. And indeed of sub-clusters within each genepool. But they can’t use any of these data, even when combined with the archaeobotanical data, to distinguish between the separate domestication and Silk Road hypotheses. 2

The archaeobotanical and genetic data thus currently present a set of signals that are not wholly consistent with either a single or multiple domestication centres for P. miliaceum. Analyses to determine the direction of migration were uninformative for our data set.

Bummer. Ah, but there is hope: the wild relative!

The genetic picture would be clarified by comparison of landrace genetic diversity with that of the wild ancestor of broomcorn millet. Analysis of microsatellite diversity in P. miliaceum subsp. ruderale could determine whether this subspecies is indeed the wild ancestor of the domesticated form, in which case the former would be expected to maintain a more diverse genepool, or a derived feral type, whose genetic diversity is a subset of domesticated P. miliaceum.

So what’s stopping them?

We did not include any samples of P. miliaceum subsp. ruderale in the current study: Although morphotypes fitting the description of this taxon are reported as being widespread across the Eurasian steppe (Zohary & Hopf 2000), detailed information or samples are not easy to find. For example, P. miliaceum subsp. ruderale is not listed on the http://www.agroatlas.ru website, and no specimens are identified as belonging to this taxon in the extensive herbarium collection of P. miliaceum at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Appropriate field collections of weedy forms of P. miliaceum for genetic comparison with cultivated types are needed, but the necessary fieldwork across vast areas of Eurasia, to give a sample set from which reliable conclusions could be drawn, would require a major international collaborative project. Our demonstration of strong phylogeographic patterning in cultivated P. miliaceum makes fieldwork and sampling of P. miliaceum subsp. ruderale a high priority for further investigation.

Well, I know what they mean, but it’s not quite as bad as that. There are in fact 10 accessions labelled P. miliaceum subsp. ruderale in Genesys, originating from 8 countries and conserved in 4 genebanks in Europe and the USA. 3 Not a great haul, but a “major international collaborative project” has to start somewhere.

From little acorns (and other tree seeds) mighty oaks (and other trees) grow

Astute followers of the Commenters to our blog will know that James Nguma, an enterprising Kenyan, is looking for scientific names for some trees his group is interested in. 4 James’ comment comes at an opportune moment. Scidev.net summarizes an article by researchers at the World Agroforestry Centre to the effect that African farmers deserve certified tree seed. 5 Why? “To help farmers know what trees they are planting so that they can make informed decisions”, according to the lead researcher. Also today, Eldis Agriculture drew attention to a 2007 report, also from the World Agroforestry Centre, that presented results from a survey of tree-nursery farmers in Malawi. And the point of this post is to ask what the people who wish to plant trees, like James Nguma and Luigi’s MIL, actually want?

My suspicion, although I have carried out neither the desk studies nor the on-site interviews to confirm this, is that they want sturdy saplings of locally sourced provenance that will grow away well and that are adapted to local conditions. Cheaply. How will certified seed serve their needs? And how can nursery owners be helped to supply them with what they need?

A third paper — Innovation in input supply systems in smallholder agroforestry: seed sources, supply chains and support systems — actually supplies answers. But it also sounds a cautionary note:

Lessons from the evolution of smallholder crop seed delivery systems can be applied to tree germplasm supply and indicate that a commercial, decentralised model holds most promise for sustainability. However, current emphasis in agroforestry on government and NGO models of delivery hinder the development of this approach.

The paper is Open Access, so you can read the whole thing and see whether you agree that neither of the two “centralized” models, Government and NGO, is actually the best way to get good quality tree seedlings into the hands of farmers who want to plant them.

Protecting Armenian vivifying tea

The Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts, commonly referred to as the Matenadaran, is well worth visiting in Yerevan. Some of the manuscripts on display are quite stunning. But apparently there’s more to the place than (very) old books. I bought this Vivifying Flower Tea in the gift shop, and the label refers to a Research Center for Medieval Armenian Medicine.

Unfortunately, there’s nothing online about this research center, but there’s clearly a lot of work around on Medieval Armenian medicine, and the role of plants in it. It’s interesting that the concoction I bought is actually protected by a patent (see the label). That’s a different route to the one taken by India, for example. The tea was in fact pretty good, if a bit expensive, though not, if I am honest, especially vivifying. I wonder if any of takings from the gift shop filters back into conservation, of either the tea’s constituent plants or the manuscripts which hold the secret of its manufacture. I suspect not.