We’ve written a fair bit about the System of Rice Intensification, or SRI, and our most recent little piece sparked what passes for a vociferous debate over at Facebook (which of course I cannot now link to). As I recall it all seemed to hinge on whether there was one SRI or several different systems, plus the fact that no-one had directly compared any kind of SRI with the alternatives. And some weird stuff about organics crept in too. Anyway, shortly after that, a piece came through the People, Land Management and Ecosystem Conservation (PLEC) News and Views listserv that reported on a close look at two different interventions to improve rice production in Timor Leste. With PLEC editor Harold Brookfield’s permission, we are pleased to repost it here.

Since East Timor’s independence as Timor Leste, the new nation has experienced an unparalleled concentration of ‘development industry’ specialists and donors determined to shape the country according to differing ideas of how development should proceed (PLECserv 118, Oct 05, 2010). Underlying this variety of styles is a familiar distinction between approaches that seek to impose change from without versus ones that foster change from within. But if this distinction is to be instructive, we need to see how each is produced in practice.

In a recent paper, Australian National University anthropologists Chris Shepherd and Andrew McWilliam contrast two examples of rice development from Timor Leste. The first scheme, initiated in 2008-2009, trialed and promoted the adoption of a technology package based on hybrid rice, mechanization, and chemical inputs within a development enclosure in the village of Tapo-Memo. The second focuses on the ‘Seeds of Life’ (SoL) programme led by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, which has been testing open-pollinated rice varieties in a large number of on-farm demonstration trials across six districts between 2006 and 2010. Both interventions have been managed by the national government. Each deployed technologies that were ‘external’ to the farmers’ world, relied extensively on scientific networks and were executed via a clear demarcation of roles between extension agents and participating farmers. Yet the way the various elements of the interventions were assembled has produced markedly contrasting farmer engagements.

In a recent paper, Australian National University anthropologists Chris Shepherd and Andrew McWilliam contrast two examples of rice development from Timor Leste. The first scheme, initiated in 2008-2009, trialed and promoted the adoption of a technology package based on hybrid rice, mechanization, and chemical inputs within a development enclosure in the village of Tapo-Memo. The second focuses on the ‘Seeds of Life’ (SoL) programme led by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, which has been testing open-pollinated rice varieties in a large number of on-farm demonstration trials across six districts between 2006 and 2010. Both interventions have been managed by the national government. Each deployed technologies that were ‘external’ to the farmers’ world, relied extensively on scientific networks and were executed via a clear demarcation of roles between extension agents and participating farmers. Yet the way the various elements of the interventions were assembled has produced markedly contrasting farmer engagements.

Using three different anthropological perspectives Shepherd and McWilliam lead the reader through a nuanced account of the two interventions. The Tapo-Memo project is a joint initiative of the East Timorese and Indonesian Ministries of Agriculture, and is directed to the market-oriented food production sector. The project drew on advanced hybrid technologies and high input management techniques supervised by Indonesian extension experts. In its first year, farmers were offered USD100 incentive payments to work collectively and ensure regular weeding and crop protection. An area of 200 hectares of demonstration gardens was carefully fenced, tilled, fertilized, sown, weeded and sprayed with pesticides. The resulting harvest produced more than three times that of local varieties and, with much enthusiasm, the local media highlighted the prospects of an expanded farmer uptake in the following year, with generalised yields as high as 8 and 12 tons/ha. These expectations did not eventuate and the project has struggled to reproduce its initial success.

Following a period of adaptive trials under Timorese conditions of seed germplasm sourced from IRRI, the Seeds of Life initiative consciously limited its technological input to on-farm trials of high yielding open pollinated rice varieties and actively encouraged participating farmers to maintain their existing farming practices. Accompanying technological improvements were downplayed in the face of reported farmer resistance to fertilizers and pesticides, as well as unreliable extension and input supply chains. With yields approaching 5 tonnes/ha and preferred Timorese eating qualities of softness, oiliness, and fragrance, the new ‘nakroma’ seed was well received by local farmers. Women reported that the new rice variety required no additional preparation time for family meals. Nakroma has subsequently become a prominent feature of local rice production especially in areas where agroecological conditions have proved particularly favourable.

These comparative interventions draw attention to the distinctive approaches and technologies deployed. The point is not that SoL was inherently successful whereas the Tapo-Memo project was not. Each intervention presented its own range of possibilities and constraints. The Tapo-Memo project required more radical adjustment of existing farming practice, including group farming methods, highly capitalized inputs and chemical agents, tractor tillage, monetary incentives and an openness to specialized extension. In contrast, SoL’s approach was delinked from a complex technological package, relied minimally on outside expertise, availed itself of existing networks, sought not to create new groups, offered no incentives, and presented no more than a few square meters of risk to farmers. This meant that there was considerably less scope for conflict, untoward appropriation, or subsequent discontent. In fact, by limiting the very range of what had to be negotiated and/or appropriated, the SoL approach generated conditions that 1) enabled farmers to trial seed as part of a data-collection regime, and 2) left farmers free to adopt the trialed seed if they felt like it.

As well as exploring rice intervention from three anthropological perspectives, the authors introduce some conceptual material from science studies. Central to their analysis is the idea of ‘boundary objects’. These at once material and conceptual objects, they say, are negotiated across social worlds (development actors and farmers) and have the qualities of both flexibility and robustness such that cooperative work can take place even if the participants have different approaches. The SoL program, it appears, had plasticity and robustness in all the right places allowing for cooperation among the parties and a relatively successful farmer appropriation. While the Tapo-Memo scheme also had qualities of plasticity and robustness, it had too much flexibility in some places (use of money incentives was inappropriate) and too much robustness in others (the technological packages required disciplined implementation in order to work). These weaknesses jeopardized the success of the project. The authors conclude that analysis of boundary objects may prove to be a useful conceptual tool in understanding the dynamics of different types of necessarily standardized interventions and how these interventions are appropriated by farmers whose agricultural practices are highly heterogeneous.

Thanks again to Harold Brookfield and PLEC. SoL has a website, and photos on Flickr, but they reserve all rights and haven’t been active for over a year, so we haven’t tried to ask permission. The Tapo-Memo project is all but invisible on the internet. Any additional information would be welcome.

![]() Taxonomy is not the most glamorous of subjects. Taxonomists who venture to suggest that well-loved Latin names might be changed to reflect new knowledge are roundly denounced. Prefer Latin names over “common” names and you are considered a bit of a dork. But taxonomy matters, becuse only if we know we use the same name for the same thing do we know that we are indeed talking about one thing and not two. And that can have important consequences, not least for plant breeding.

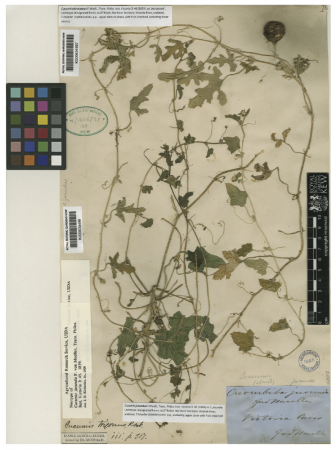

Taxonomy is not the most glamorous of subjects. Taxonomists who venture to suggest that well-loved Latin names might be changed to reflect new knowledge are roundly denounced. Prefer Latin names over “common” names and you are considered a bit of a dork. But taxonomy matters, becuse only if we know we use the same name for the same thing do we know that we are indeed talking about one thing and not two. And that can have important consequences, not least for plant breeding. A new paper takes a close look at some old herbarium specimens, originally collected in 1856 by Ferdinand von Mueller. 1 Mueller was born in Germany in 1825 and went to Australia in 1845, for his health. There, in addition to being a geographer and physician, he became a prominent botanist. He collected extensively, including a long expedition to northern Australia in 1855-6. There he collected many specimens that turned out to be new to science, including two new melons that he called Cucumis jucundus and C. picrocarpus. The two of them are preserved on this herbarium sheet at Kew.

A new paper takes a close look at some old herbarium specimens, originally collected in 1856 by Ferdinand von Mueller. 1 Mueller was born in Germany in 1825 and went to Australia in 1845, for his health. There, in addition to being a geographer and physician, he became a prominent botanist. He collected extensively, including a long expedition to northern Australia in 1855-6. There he collected many specimens that turned out to be new to science, including two new melons that he called Cucumis jucundus and C. picrocarpus. The two of them are preserved on this herbarium sheet at Kew.

Joseph Needham is known as the

Joseph Needham is known as the