![]() When we talk about plant traits here we are usually referring to things like characterization and evaluation descriptors, and how they vary within crops. But there’s an ambitious initiative underway to document “the morphological, anatomical, physiological, biochemical, and phenological characteristics of plants and their organs” — some 1500 of them — across the world’s entire wild flora. It’s called TRY, and it is described in a new paper in Climate Change Biology. 1 It works by bringing together existing datasets in a data warehouse, like this:

When we talk about plant traits here we are usually referring to things like characterization and evaluation descriptors, and how they vary within crops. But there’s an ambitious initiative underway to document “the morphological, anatomical, physiological, biochemical, and phenological characteristics of plants and their organs” — some 1500 of them — across the world’s entire wild flora. It’s called TRY, and it is described in a new paper in Climate Change Biology. 1 It works by bringing together existing datasets in a data warehouse, like this:

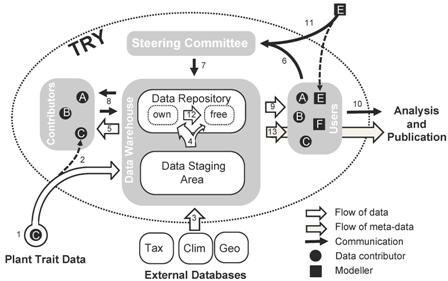

I think the caption to this diagram (Fig. 1 in the paper) is worth quoting in full, as it may give some ideas to people developing similar systems more aimed at agrobiodiversity, like Genesys.

The TRY process of data sharing. Researcher C contributes plant trait data to TRY (1) and becomes a member of the TRY consortium (2). The data are transferred to the Staging Area, where they are extracted and imported, dimensionally and taxonomically cleaned, checked for consistency against all other similar trait entries and complemented with covariates from external databases (3; Tax = taxonomic databases, IPNI/TROPICOS accessed via TaxonScrubber (Boyle 2006), Clim = climate databases, e.g. CRU, Geo = geographic databases). Cleaned and complemented data are transferred to the Data Repository (4). If researcher C wants to retain full ownership, the data are labelled accordingly. Otherwise they obtain the status ‘freely available within TRY’. Researcher C can request her/his own data – now cleaned and complemented – at any time (5). If she/he has contributed a minimum amount of data (currently >500 entries), she/he automatically is entitled to request data other than her/his own from TRY. In order to receive data she/he has to submit a short proposal explaining the project rationale and the data requirements to the TRY steering committee (6). Upon acceptance (7) the proposal is published on the Intranet of the TRY website (title on the public domain) and the data management automatically identifies the potential data contributors affected by the request. Researcher C then contacts the contributors who have to grant permission to use the data and to indicate whether they request co-authorship in turn (8). All this is handled via standard e-mails and forms. The permitted data are then provided to researcher C (9), who is entitled to carry out and publish the data analysis (10). To make trait data also available to vegetation modellers (e.g. modeller E) – one of the pioneering motivations of the TRY initiative – modellers are also allowed to directly submit proposals (11) without prior data submission provided the data are to be used for model parameter estimation and evaluation. We encourage contributors to change the status of their data from ‘own’ to ‘free’ (12) as they have successfully contributed to publications. With consent of contributors this part of the database is being made publicly available without restriction. So far look-up tables for several qualitative traits (see Table 2) have been published on the website of the TRY initiative (http://www.try-db.org). Meta-data are also provided without restriction (13).

How far has it worked?

As of 31.03.2011 the TRY data repository contains 2.88 million trait entries for 69,000 plant species, accompanied by 3.0 million ancillary data entries15. About 2.8 million of the trait entries have been measured in natural environment, less then 100.000 in experimental conditions (e.g. glasshouse, climate or open top chambers).

Here’s the distribution of the 3458 geo-referenced sites where leaf nitrogen content per dry mass was measured. The grey areas are places where the various species on which the measurements were made can be found, according to GBIF. Not exactly global coverage just yet, but not bad. Interestingly, an analysis of the data available thus far showed that though most of the variation in most traits was at the species level, up to 40% was intraspecific.

Coincidentally (or maybe not?) there’s also a paper just out in New Phytologist which looks at the global distribution of a particular class of plant traits, those associated with resistance to herbivores. There’s no reference to TRY in the paper, but a couple of the same people are involved, and I think this is one of the datasets that have been contributed to the warehouse. 2

We worked at 75 study sites, distributed from 74.5°N to 51.5°S… Sites were selected to sample the dominant vegetation types at a wide range of latitudes… [T]he primary criterion [for site selection] was that the levels of herbivory, disturbance regime and plant community composition should be relatively natural (i.e. as close as possible to those with which the plant traits we are measuring are thought to have evolved). At each site, we sampled the four most abundant species…

The key finding was that despite the long-held belief that tropical plants are in general more resistant to herbivory than those from temperate climes, there is actually little evidence of this in the data. If anything, the trend is in the opposite direction. I wonder whether that will hold within species (or genepools) as well as across them.