Sorry for the slow blogging, but I’m ill in bed and Jeremy is travelling. But none of that will stop us from wishing you all a happy International Women’s Day!

Ancient wild relatives

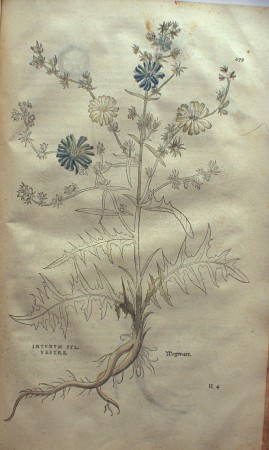

While we’re on the subject of radicchio diversity, old Roman medicines and the like, we were pleased to be sent a link to Renaissance Herbals, a collaboration between the Smithsonian Institution and the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma. There are some lovely images to peruse and use, like this one, of wild chicory, Cichorium intybus.:

One could complain, of course, that the links between the illustrations and other sorts of information are non-existent. But hey, you can’t have everything.

More on ancient Roman pills

What I missed when I wrote about the 2000-year-old Roman pills a couple of days back is that the research was highlighted by Discover magazine as one of the Top 100 Stories of 2010. In addition, Emanuela Appetiti, one of the researchers involved, kindly pointed me to a story at AoLNews which has lots more photos and another one in the Washington Post. She also gave me this nice bit of news:

…I am happy to inform you that Alain Touwaide and myself, along with Rob Fleischer, the geneticist who did the DNA analysis of the ancient medicines, will be in Rome in mid-May 2011 (on the occasion of the “Night of the Museums”) to present at “La Sapienza” University this research. For the first time, we’ll be all there: the three of us and the staff of the Soprintendenza di Firenze, who did the archeaological digging and first analysis. The event in Rome will be on May 14, 2011, at the faculty of Letters.

Looking forward to that. In the meantime, here’s a very recent interview with Alain Touwaide, courtesy of the BBC. Thanks, Emanuela.

Eating Jamaican

From Our Man in Kingston, Colin Khoury. Thanks, mon, and Jah guide.

We are here in Kingston, Jamaica due to a EU funded project “Strengthening Jamaica’s Food Security Programme”. Yesterday, as part of the project, the Government, in partnership with FAO and the EU, launched a campaign entitled “Eat Jamaican”, which brought the dignitaries and star athletes to the large Coronation Market in downtown, where produce from all over the island is brought in by “higglers” be sold. The campaign will promote awareness of the benefits of eating Jamaican through the radio and newspapers, and have road shows, chef “cook-offs”, display booths, celebrity endorsements, a comedy corner, and more.

Committing to walking the walk (and, to be honest, discouraged by the very high price of food on this island, especially the imported stuffs) we are going to be eating as Jamaican as possible. If we had a garden, I’d take up the Government on its suggestion to “grow what we eat; eat what we grow”, but for now we will need to gather what we eat from the markets of this capital city.

So what is it to eat Jamaican? In Coming Home to Eat, Gary Nabhan studied the indigenous diet of his American Southwest home and then, modelling this diet, attempted for a year to source 80% of his consumption from within a local radius of 350 km, the remaining 20% from further afield. As we are on an island, the boundaries for us are clear — Jamaica is 235 km long and 80 km wide. It would be nice to be able to draw a line in the water as well and see if we can source our fish as locally as possible.

It seems like it can’t be that difficult. Jamaican cuisine is, after all, diverse and interesting. The famous “jerk” sauces and other curries smother the meats and fish, tropical fruit abounds, and “rice and peas” (actually rice and Phaseolus beans), cassava “bammies”, and bananas/plantains accompany the meals.

It seems like it can’t be that difficult. Jamaican cuisine is, after all, diverse and interesting. The famous “jerk” sauces and other curries smother the meats and fish, tropical fruit abounds, and “rice and peas” (actually rice and Phaseolus beans), cassava “bammies”, and bananas/plantains accompany the meals.

But how much of Jamaican cuisine is Jamaican produced? It’s amazing how long a trip to the supermarket becomes when you stop to read labels. And the results can be surprising- there are a lot of foods “made in Jamaica” that are processed and packaged here, but the crops themselves are produced elsewhere. This is likely to be true of most of the chicken topped by that famous jerk, and certainly for the breads and breakfast cereals. In buying these foods, we are supporting the local economy, but not doing anything to support local food producers.

But how much of Jamaican cuisine is Jamaican produced? It’s amazing how long a trip to the supermarket becomes when you stop to read labels. And the results can be surprising- there are a lot of foods “made in Jamaica” that are processed and packaged here, but the crops themselves are produced elsewhere. This is likely to be true of most of the chicken topped by that famous jerk, and certainly for the breads and breakfast cereals. In buying these foods, we are supporting the local economy, but not doing anything to support local food producers.

In another twist, there are products made from local foods, and processed and packaged here, yet sold under the label of multinationals such as Nestlé. So with this purchase we seem to be supporting both local food production as well as the food product giants.

The simplest and cheapest way to purchase and eat locally here is probably to buy the local grains and legumes in bulk, and the fresh produce, and eat at home. This can be challenging with busy work schedules. It also involves a shift from some of the staples we are used to, such as wheat and oats, to rice and roots/tubers such as yam and sweet potato.

The agronomists working for FAO here tell me that almost anything can be grown, from lettuce to breadfruit, and almost everything is exported in some quantity (but not as much as could be). Jamaica isn’t a huge island, but it is topographically diverse. So eating locally is likely not to constrain our diets terribly.

But if we are working to have local food production contribute to long-term food security, we need to ask the next logical question — what local foods can be produced easily in the agroecosystems of this island, without the need for excess protective chemicals, greenhouses, shadehouses, or irrigation? One direction to look might be the foods with a long history on this island.

Otaheite (Syzygium malaccense) has a lovely, tropical pear kind of taste, and is native to Indonesia and Malaysia, a Captain Bligh introduction from Timor and Tahiti in 1793. The national fruit, Ackee (Blighia sapida) looks and kind of tastes like scrambled eggs, is best mixed with salty fish, and fills you up for the whole day. Ackee is West African in origin, and is named after Bligh due to his interest in the fruit, which he brought from Jamaica back to England.

Otaheite (Syzygium malaccense) has a lovely, tropical pear kind of taste, and is native to Indonesia and Malaysia, a Captain Bligh introduction from Timor and Tahiti in 1793. The national fruit, Ackee (Blighia sapida) looks and kind of tastes like scrambled eggs, is best mixed with salty fish, and fills you up for the whole day. Ackee is West African in origin, and is named after Bligh due to his interest in the fruit, which he brought from Jamaica back to England.

The maize, “peas”, squash, cassava, yams, tomatoes and “scotch bonnet” peppers native to Mesoamerica have likely been here since the Arawak were doing their thing in pre-Colombian times. One great discovery has been that the most common green leafy vegetable here- callaloo- that at first I took to be a Brassica similar to the collard greens popular in the Southern US, turns out to be Amaranthus. Now that is an eco-efficient, climate change ready, food security vegetable if ever there was one.

The banana producers here, who have been plagued by crop-destroying hurricanes in the last years, may need to transition to alternative crops. My hope is that this transition is toward larger production of the foods that do grow well here, and are hardy toward the climate challenges to come.

The banana producers here, who have been plagued by crop-destroying hurricanes in the last years, may need to transition to alternative crops. My hope is that this transition is toward larger production of the foods that do grow well here, and are hardy toward the climate challenges to come.

There also seems to be much to be done simply to improve the quality (i.e. appearance) of the local food crops, to make them more appealing to consumers. Creating recognition for local foods, as has been done with the coffee grown in the Blue Mountains not far from Kingston, may also help consumers to appreciate what is at their fingertips.

Proactive and supportive consumerism — which may be half the battle to achieve a sustainable food system in contribution to long-term food security — is something that will come with a good deal of education, effort and a lot of label reading.

And that 20% we allow ourselves to get from elsewhere, you ask? So far, the results indicate that it is likely to be comprised highly of sharp cheddar cheese, wine and olives.

Radicchio diversity

Following in Luigi’s footsteps, the botanic gardens at Padua beckoned. The oldest botanic gardens in the Old World (Wikipedia is wrong; the New has older) they have operated continuously in the same place since 1545. A freezing February day was not ideal to see plants, and precious few of the labels denoted anything directly edible as food. I was not, however, entirely disappointed, for in a sunny bed in the lee of a building was a display of perhaps the region’s most famous crop: radicchio.

The picture above shows an old local variety, Variegato di Castelfranco, and Otello, a modern cultivar. Which, naturally, sent me scurrying to discover more about their history and breeding. There isn’t, actually, a huge amount. One study, of which I’ve seen only the abstract, examined DNA diversity of the five major types. Turns out that if you compare pooled bulk DNA from six individuals of each type, the different types are easy to distinguish. If, on the other hand, you look at DNA from individuals, the distinctions disappear. The variation within a single type is much greater than the variation among the different types. This, the researchers say, indicates that the types have maintained their “well-separated gene pools” over the years. An earlier paper (available in full) had come to a similar conclusion about the populations, with what seems like an ulterior motive: 1

The molecular information acquired, along with morphological and phenological descriptors, will be useful for the certification of typical local products of radicchio and for the recognition of a protected geographic indication (IGP) mark.

And lo, it came to pass. Four types (I think early and late Rosso di Trevisos are included in one designation) got their Protected Geographical Indication in 2008 and 2009. That’s late — tardivo — in the photograph below.