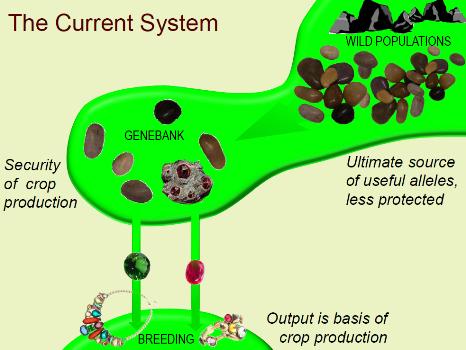

The presentation on genomics and fruit genebanks Cameron Peace gave at the recent PAG symposium deserved more than the nibble we gave it. Dr Peace, who is an assistant professor in tree fruit genetics at Washington State University, is advocating nothing less than a complete change in the mindset of genebank curators. Here’s how he characterizes the current system:

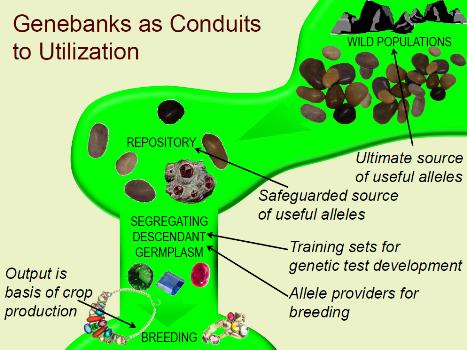

Notice the mere trickle of material from the genebank to the user. All too true. I would say that there is also much less movement of material from wild populations to genebanks than is suggested by the diagram. But that’s at least partially down to the fundamental fact that flow of material to breeders is fairly limited. No demand, no supply. This, in contrast, is what Dr Peace wants to see:

He wants genebanks to get their skates on and, to mix a metaphor, not wait for the breeders to pull. He wants them to push. He wants them to provide performance information, and not just data on morphological descriptors; performance-predictive DNA information, and not just genetic diversity data; segregating descendant populations, and not just landraces or wild populations.

In essence, Dr Peace wants genebank curators to think like breeders. More, he wants them to be breeders. Or at least pre-breeders.

There’s much to be said for this. The latest State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (SOW2) bemoans the continuing obstacles to use of collections. Something Must Be Done, it suggests. But curators have their hands full. The same SOW2 says that they have no money. That they need more equipment. That they have regeneration backlogs. That people are telling them to conserve more neglected and underutilized plants, and more crop wild relatives. That’s when armed gangs of looters are not ransacking their facilities. Now they should be plant breeders as well? Sheesh!

Well, the fact is that with the International Treaty on PGRFA, most curators don’t have to worry about basic conservation. Not really. Not for Annex 1 crops anyway. They can choose to outsource that stuff, for example to the international centres of the CGIAR, secure in the knowledge that they can have access to the material whenever they want it.

With the ITPGRFA, curators have the space to think like breeders. But do they have the training? And will the breeders return the compliment, and think a bit like curators?