Wild relatives of apples, cherries, almonds and grapes are to be found in this landscape, apparently. More later on my trip.

European production and yield data online

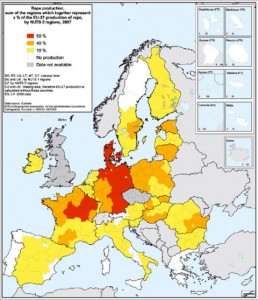

Just a quick addendum to the recent discussion of maps of crop production statistics. I’ve found a source of geographical data on crop production for Europe. And also one on yield forecasting in Europe (and elsewhere) based on satellite imagery.

Just a quick addendum to the recent discussion of maps of crop production statistics. I’ve found a source of geographical data on crop production for Europe. And also one on yield forecasting in Europe (and elsewhere) based on satellite imagery.

Genebanks all the more necessary in a 4°C+ world

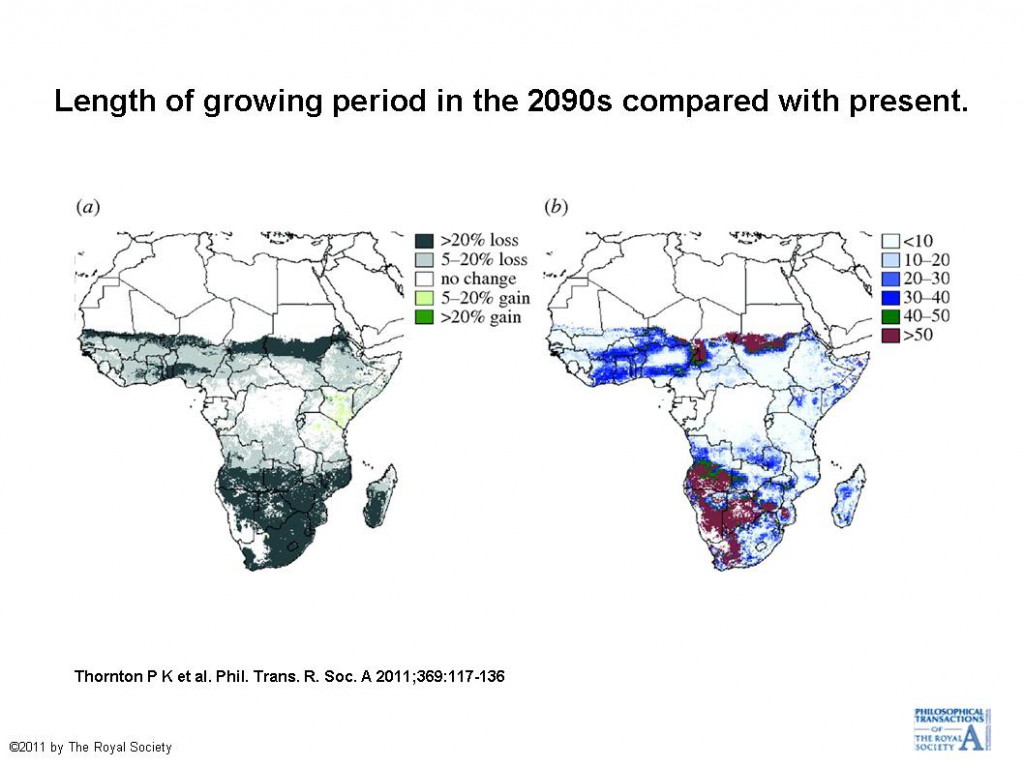

As adaptation starts to come in from the, er, cold, a paper in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Series A looks at what a possible 4°C warming will mean for African agriculture. It isn’t pretty.

…maize production is projected to decline by 19 per cent and bean production by 47 per cent, all other things (such as area sown) being equal…

But the authors do have some ideas about what to do, policy-wise:

Thornton and colleagues highlight four areas for immediate policy attention: supporting farmers’ own risk-management strategies, strengthening basic data collection in agriculture, investing seriously in genebanks, and improving governance of food systems so that poor people can get affordable food.

This is what the authors say about genebanks in particular:

…concerted action is needed to maintain and exploit global stocks of crop germplasm and livestock genes. Preservation of genetic resources will have a key role to play in helping croppers and livestock keepers adapt to climate change and the shifts in disease prevalence and severity that may occur as a result. Genetic diversity is already being seriously affected by global change. Genetic erosion of crops has been mostly associated with the introduction of modern cultivars, and its continuing threat may be highest for crops for which there are currently no breeding programmes. Breeding efforts for such crops could thus be critically important. For livestock, about 16 per cent of the nearly 4000 breeds recorded in the twentieth century had become extinct by 2000, and a fifth of reported breeds are now classified as at risk. Using germplasm in SSA will need technical, economic and policy support. Revitalizing agricultural extension services, whether private or in the public sector, is key: no farmers will grow crops or raise livestock they do not know, are not able to sell, and are not used to eating.

Well, I find that a bit confused, in truth, but it is nice to see genebanks (and, incidentally, their databases) getting their due. They are all too often taken for granted. 1 But well-run genebanks on their own are not enough, though they are definitely necessary. The material in them must also be easily accessible, and for that you need the sort of political infrastructure provided by the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

A brave new world for crop wild relatives

Thanks to Dr Brian Ford-Lloyd of the University of Birminghan in the UK for the following contribution.

A ground breaking publication in Nature Genetics points to the future for the genetic evaluation of crop wild relative germplasm. A group of Chinese scientists have used Illumina Next Generation Resequencing to produce whole genome sequences of 17 wild species of soybean. Only 17 wild species? But this is just the start for evaluating crop wild relatives on a completely different level than before — adding a different perspective to the analysis of genetic diversity, the identification of important adaptive differences between species, and locating novel allelic variation that can be used in crop improvement. One important result from the work is that they uncovered genetic variation in the wild species that has been clearly lost in cultivated material.

Tough questions about agricultural research

First, has the decline in funding and the shift toward a breakthrough science model left us adequately prepared to solve the problems with our national and global food system? And second, would simply bolstering, as opposed to also broadening, our current system of agricultural research be an adequate response?

Us, in this case, being the US.

Paul B. Thompson, the W.K. Kellogg Chair in Agricultural, Food and Community Ethics at Michigan State University, had a great post in the run-up to Thanksgiving that I missed last week. He points out that Americans have been “disinvesting” in agricultural research and development over the past three decades, and that what investment there was has been “too narrowly focused on piecemeal adjustments in plant and animal genetics”.

Thompson then gives a run-down on the history of agricultural research in the US, and how it changed, especially in the wake of the Pound report in 1975. And despite the efforts of farm lobby groups, who fought to preserve the old system of land-grant universities and research, agricultural research and the ways it was funded altered in fundamental ways. Why? As Thompson notes of the USDA’s effective approach to solving farmers’ problems,

Despite its utility, however, this was not especially sexy science.

The analysis goes on to look at the rise in popularity of alternative “low-input methods such as organic, no-till, and poly-crop” approaches to farming, and at how, and why, these approaches have been so ill-served by research and research funding. What I find so remarkable is that Thompson’s detailed look at the USDA finds a mirror in research for poorer countries. Here’s what he has to say:

There is debate about these alternative approaches here in the United States, but there is really no debating the fact that poor farmers around the world could imitate many of [these] farming practices, given some adaptive research that tailors them to local soils and climate. In contrast, the more industrial approach requires two things that poor farmers lack. One is the infrastructure of local seed, fertilizer, and chemical companies, along with an effective regulatory system to monitor the impact of high-tech farming. The other is the money to buy these inputs from the private sector, even when they are available.

There is much more that repays a close reading; for example:

[T]he organic farming community’s attraction to vitalistic metaphors and unsubstantiated health-claims alienated many scientists whose careers depended upon pursuing a research program that could pass the laugh test. … [R]esearch focused on genomics and genetic engineering was much more promising to a budding scientist than the iffy strategy of partnering with the organic growers.

Lets forget about organic, for now, and the laugh test as a measure of scientific value, and see US scientists renew the old-fashioned approach to food and nutrition security, because clearly where US agriculture leads, the rest of the world follows.