Elizabeth Andoh, an American who has lived in Japan for 25 years, talks about “food that is not what it seems.” Modoki has nothing really to do with deception, it is all about having fun with your food. Links to Buddhist cuisine of China, vegetarian and vegan stuff, often made to resemble stuff that did have the potential for life.

There is an ancient Japanese book called “100 things to do with tofu.”

She shows a picture of real eel (I’m not getting the names, thanks to the PA) and then a fake (modoki) that is visually identical, down to the surface look of the “fish”. Gobo (burdock root) and lotus root help the whole thing to stick together.

“You have to have keen powers of observation and to take into consideration texture even more than taste. Truly, if you closed your eyes, you would think you were eating eel.”

Now we’re onto Ganmodoki, which is a version of goose meatballs, no goose meat.

“Soy milk skins sound like something even a dermatologist doesn’t want to know about.” They have a wonderful unctuous texture and a creamy feel in your mouth. They perish easily, and are dried, but can be resuscitated by wrapping in a damp cloth. Resemble a thin omelette, an impression that can be enhanced by adding the dried seeds (or buds?) of a gardenia, which “bleed an intense neon yellow”. The end result can be shredded and used as “eggs” in other dishes.

Pseudo-chestnuts made of fish and shellfish meat and fried noodles with a whole-roast chestnut poked inside, provoking a memory of the whole chestnut.

A teeny tiny persimmon made from a dyed quail’s egg with a piece of kombu stuck to the top.

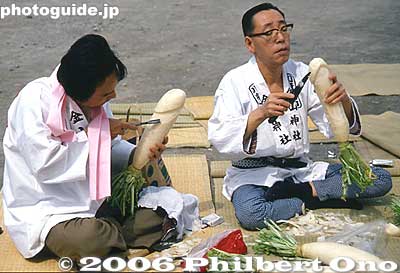

One of the elements in modoki is sheets of daikon radish, which take an amazing amount of skill to make: watch this.

A perfect segue into Michelle Toratani, who takes the floor to talk about a very particular individual daikon, “the fighting root”. A very bizarre story.

How did a vegetable root become a super-hero? Because it is such an important daily vegetable in Japanese life. People can really identify with it.

On to the proper stuff. Daikon originated in China, came to Japan about 1000 years ago. There are about 100 regional varieties of daikon. Don’t have to be white, can be red or deep purple.

Frankly, there’s so much here about the daikon in culture (some of which Luigi nibbled), that I really don’t want to get into here on a Sunday morning. See for yourself. Or Google Daikon Penis.