As designated rice-editor at the Agricultural Biodiversity Weblog, this clipping from The Nation, a Sri Lankan newspaper, landed on my desk. But I am not sure what to make of it.

Researchers (or farmers?) have discovered a (new?) type of rice that can be vegetatively propagated:

The long Mavee rice plant can be cut in pieces and sown to grow as any normal rice. It took the researchers nearly six years to find the specific qualities in the Mavee cultivation, and those plants that contained this quality were later named as Maha Mavee.

Mavee is a variety, maha means wet season (as opposed to yala, the dry season). And as it grows up to “10 feet during flash floods” (that’s quick!) I suppose it is a ‘deep-water’ or ‘floating’ rice type.

So what? Well, the newspaper calls them miracle plants. According to “attorney-at-law and a renowned environmentalist,” Jagath Gunawardane, this is a big deal:

The discovery of this new method of vegetative propagation is likely to revolutionise the entire industry. The Government now needs to help the farmers maintain this cultivation technique, and also prevent companies from claiming patent rights for this ground breaking breakthrough in the agricultural field.

Presumably because of savings in seed cost. Interesting. But then again there are four or five “miracle rices” discovered every year…

To briefly go off on a tangent in an area that I am not a total dummy about, I recently learned the word “asweddumized.” I came across it in the (English language) agricultural statistics of Sri Lanka. I was told that the word was first introduced in 1958 by S.W.R.D. Bandaranayaike, then the Sri Lankan Prime Minister. It stems from the Sinhala word “aswaddanawa,†meaning converting forest land into cultivatable land that has bunds for retaining either irrigation or rainwater, mainly for rice.

But back to the subject at hand. What do you think the prospects are for Maha Mavee? Are there examples of normally seed propagated crops that become vegetatively propagated? Fruit trees through grafting is one example, but that is for a different reason: the propagation of a particular genotype, rather than saving seeds.

People have tried the opposite with potatoes. It seems obvious: ‘true’ (botanical) potato seed is much cheaper than seed tubers, carries fewer diseases, can be stored, etc. But this has not been very successful. Potato was too variable from seed (which makes it so much fun to try this at home), as quality (uniformity and size) is important in the market, and yields were lower. The International Potato Center (CIP) has worked on these issues, and Hubert Zandstra (a former director of CIP) remains optimistic about these seeds, and particularly about their benefits to poor farmers. He thinks that early ‘bulking’ (the formation of tubers) and apomixis may save the day for true potato seed.

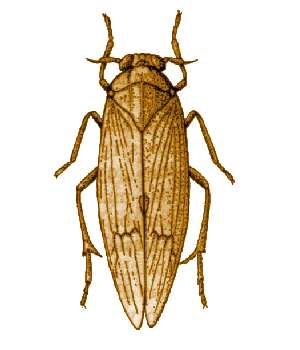

Spraying is what many farmers do, to the detriment of their health and environment. It also makes the pest problem worse. Why? Because pesticides also kill the pests’ natural enemies, such as spiders. So you need to spray again, and again. Until the pests are pesticide resistant. This has led to huge outbreaks of brown plant hopper, like in Indonesia in the 1980s, which only stopped after most pesticides were banned. ((Brown plant hopper image from

Spraying is what many farmers do, to the detriment of their health and environment. It also makes the pest problem worse. Why? Because pesticides also kill the pests’ natural enemies, such as spiders. So you need to spray again, and again. Until the pests are pesticide resistant. This has led to huge outbreaks of brown plant hopper, like in Indonesia in the 1980s, which only stopped after most pesticides were banned. ((Brown plant hopper image from