We’ve been keeping a weather-eye on the new strain of wheat stem rust called UG99 (it was isolated in Uganda in 1999) since very early in the history of this blog, trying to keep at least vaguely abreast of its spread and efforts to fight it. In truth, it has not been a very happy story, and if our coverage has dropped off just a bit, that may be because it can get tiresome crying wolf, no matter how much joy it might give us to be proved right.

Anyway, there’s been another outburst of interest, and while the news still isn’t good, it is fun to see how different people tell the story. First off, there’s The Hero :

Like the warrior Beowulf, subject of the Old English epic poem, [Norman] Borlaug slew a monster, saved his world and lived to a ripe old age. Like Beowulf, this old warrior of science has had to climb back into armour to battle the rise of a new monster. And once again, the world is looking to him for salvation.

Elizabeth Finkel, teller of that particular tale, certainly has a sense of drama. 1 And she gives a very full account of the fight against wheat rusts in general. Across it all strides Borlaug, whom Finkel describes as “frail”. Any 95-year old is entitled to be frail, but my understanding is that he is in worse shape than that. How will the scientists and funders fare in his absence? I hope they redouble their efforts, in memoriam as it were.

Then there’s the army of soldier ants, selflessly toiling in defense of the greater good:

After several years of feverish work, scientists have identified a mere half-dozen genes that are immediately useful for protecting wheat from Ug99. Incorporating them into crops using conventional breeding techniques is a nine- to 12-year process that has only just begun. And that process will have to be repeated for each of the thousands of wheat varieties that is specially adapted to a particular region and climate.

Karen Kaplan’s story, in the LA Times, is as broad as Finkel’s, but paints a different picture. Borlaug doesn’t even get a name check. Instead, scientist after US scientist gets a brief moment to explain how complex and yet tedious the job is, how ill-prepared they were, how each depends on all the others, and how the rest of humanity depends on them. We need both stories, I think, scientist as individual hero and scientist as soldier ant, breakthrough and toil, and I hope readers get them.

Yet another narrative crops up, though. I’m not sure what to call it. Pot of Gold? Silver Lining? Unexpected Benefit?

Crop scientists have discovered a new threat to wheat crops within the United States, leading to a race to be the first to breed a resistant wheat plant, before there is trouble. Any outcome could have a big effect on related agriculture exchange traded funds (ETFs).

Setting aside all the guff about the threat being “new,” Tom Lydon, in Commodity Online, points his readers to two such exchange traded funds, noting that “fear that the fungus will cause widespread damage has caused short-term price spikes on world wheat markets”. In other words, there may be money to be made.

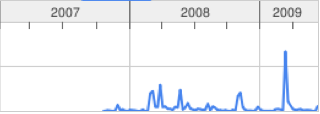

Why the current spate of interest? That’s hard to say. There have been meetings in Mexico and Syria, which account for the most recent spike in Google Trends. But nothing that I have noticed more recently than that. Just coincidence, perhaps. And in all the stories about how to deal with UG99, there’s one that has been conspicuous by its absence. Don’t Put All Your Eggs in One Basket.

Why the current spate of interest? That’s hard to say. There have been meetings in Mexico and Syria, which account for the most recent spike in Google Trends. But nothing that I have noticed more recently than that. Just coincidence, perhaps. And in all the stories about how to deal with UG99, there’s one that has been conspicuous by its absence. Don’t Put All Your Eggs in One Basket.

Faced with the cost of controlling disease in monoculture, two solutions emerged – to keep producing new varieties and new fungicides. But both of these solutions led to the Red Queen problem in Lewis Carroll’s ‘Through the Looking Glass’: ‘Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place’. Mixtures of appropriate varieties, however, can restrict disease and increase yield reliably, without need for fungicides.

Martin Wolfe is the name perhaps most associated with the renaissance of the idea that mixtures may be the way to cope with at least some diseases. That’s something else we’ve written about before, but as far as I know there have been no trials designed specifically to ask how wheat mixtures fare under UG99. Seems at least worth a try.

- She’s also been busy lately.

Jeremy: In the link you give to Martin Wolfe, he promotes the Zhu, Y. et al. Nature 406, 718-722 (2000) paper as an example of rice varietal mixtures coping with blast disease. This paper has now been queried (rather coyly) in a paper in Field Crops Research.

These authors found that the disease-susceptible traditional rice variety was also lodging-susceptible. The interplanted modern variety stopped the traditional variety falling over and thereby increased its yields (the Zhu. et al. paper is equally coy on reasons for the actual yield effect). A good result for the value of varietal mixtures, but not necessarily for disease suppression.

Further, on UG99 — assumptions are being made that it started life in Uganda. Far more likely UG99 came from Ethiopia, which, with its huge varietal (and species) diversity of wheat, is a hotbed/nursery/reservoir (or whatever) of wheat diseases. In the 1970s the USSR had a ‘Phytopathological Research Unit’ at Ambo in Ethiopia for just this reason.

The current fashion for the on-farm conservation of crop diversity ignores the inevitable conservation of diverse plant diseases, some of which, like Ug99 of wheat, can cross continents on the wind and threaten crop production globally.

@ Dave: Leaving aside the question of lodging, which I dealt with in my post about Zhu, you also said “The current fashion for the on-farm conservation of crop diversity ignores the inevitable conservation of diverse plant diseases, some of which, like Ug99 of wheat, can cross continents on the wind and threaten crop production globally.”

Do you have evidence of the opposite point of view, that large monocultures of resistant varieties have caused the extinction of particular strains of any disease, or indeed any pest?

Jeremy: I seem to have lost the `Featured Comment’ where you say that conserving crop varieties on farm conserves pathogens. How can I recover it? It is important. We might know this, but do donors in Europe paying for, let’s say, conserving potato varieties in Peru, know they are also conserving some nasty diseases. More to the point, would they do this in Switzerland, or the Netherlands, or Norway where it would threaten their own production? It seems to be a case of `not in my back yard’, at the expense of developing countries.

Monocultures and disease extinction is interesting. It could be done in controlled experiments where a new pathotype generated by mutation was introduced to a glasshouse with a susceptible and a resistant variety. After one season, the susceptible (and now diseased) variety could be herbicided quite dead. With reduced crop diversity, the following monoculture of the resistant variety would not allow the new pathogen to recover from `extinction’. But it is a bit academic – the aim of pathologist and plant breeders is to reduce the impact of disease by breeding resistant varieties, not to make pathogens extinct. They will always either hang in somewhere under traditional farming and in the wild or continue to evolve new strains (n.b. I am not a pathologist).

After the Green Revolution in India, farmers were forbidden to cultivate old, disease susceptible, varieties of wheat as these inoculated disease into the newer varieties (and farmers hid the old, preferred, varieties inside plots of the new ones). In Australia a farmer growing disease susceptible durum wheat in a bread wheat area had disease resistance bred into his durum wheat at state expense to prevent inoculation of the bread wheat. This is anecdote and I would like to hear of more examples.

Crop diseases are a long way from human diseases. I was in Ethiopia at the time smallpox was made extinct (apart from a few lab colonies).