There’s a very interesting article in the New York times reporting on a major investigation of the molecular diversity among grape cultivars.

The report is based on a big paper in PNAS, which I confess I have not had time to read carefully. That said, a few things about the NYT’s coverage confuse me. One is the whole depiction of “relatedness”.

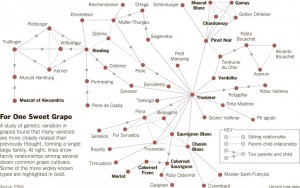

Thus merlot is intimately related to cabernet franc, which is a parent of cabernet sauvignon, whose other parent is sauvignon blanc, the daughter of traminer, which is also a progenitor of pinot noir, a parent of chardonnay.

This web of interrelatedness is evidence that the grape has undergone very little breeding since it was first domesticated, Dr. Myles and his co-authors report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

So how did those varieties arise? Maybe breeding means only “deliberate crosses made by a breeder”. Are they saying that the molecular data support the breeding records? Or are actual breeding records, especially for the older and better-known varieties, too sketchy to know? There’s more too, but I’m going to have to find time to read the PNAS paper properly. Or maybe you already have, in which case, feel free to comment.

Jeremy: I do not have the paper in front of me, but I think they say varieties arise by somaclonal mutation – that is, not by accidental or deliberate crossing. Therefore no actual breeding and segregation, but presumably intense human selection for quality with lots of rejects. Perhaps a geneticist could comment: this may also be the mechanism for new banana and hop varieties and other clonally propagated varieties.

The data are pretty interesting. Almost 60% of the samples they looked at are clones of other samples at the loci they examined. That implies that they are selected somatoclonal mutations. But there has also been quite a bit of introgression back and forth with wild grapes. What struck me is that grapes have actually conserved far more of the diversity seen in the wild population than, say, tomatoes or maize, but that that diversity is relatively similar among all the different grape varieties. And that’s where the authors say the problem lies, because what selection there has been has been relatively restricted and so the rest of the genome, which is where resistance to pests and diseases is likely to be, is relatively similar and, hence, they argue, relatively vulnerable.