![]() Taxonomy is not the most glamorous of subjects. Taxonomists who venture to suggest that well-loved Latin names might be changed to reflect new knowledge are roundly denounced. Prefer Latin names over “common” names and you are considered a bit of a dork. But taxonomy matters, becuse only if we know we use the same name for the same thing do we know that we are indeed talking about one thing and not two. And that can have important consequences, not least for plant breeding.

Taxonomy is not the most glamorous of subjects. Taxonomists who venture to suggest that well-loved Latin names might be changed to reflect new knowledge are roundly denounced. Prefer Latin names over “common” names and you are considered a bit of a dork. But taxonomy matters, becuse only if we know we use the same name for the same thing do we know that we are indeed talking about one thing and not two. And that can have important consequences, not least for plant breeding.

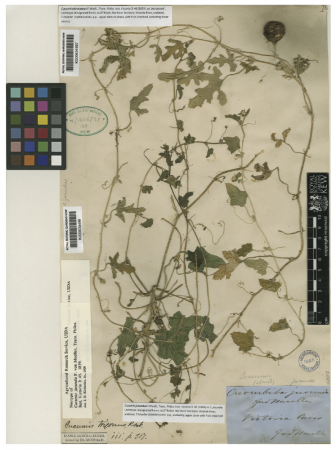

A new paper takes a close look at some old herbarium specimens, originally collected in 1856 by Ferdinand von Mueller. 1 Mueller was born in Germany in 1825 and went to Australia in 1845, for his health. There, in addition to being a geographer and physician, he became a prominent botanist. He collected extensively, including a long expedition to northern Australia in 1855-6. There he collected many specimens that turned out to be new to science, including two new melons that he called Cucumis jucundus and C. picrocarpus. The two of them are preserved on this herbarium sheet at Kew.

A new paper takes a close look at some old herbarium specimens, originally collected in 1856 by Ferdinand von Mueller. 1 Mueller was born in Germany in 1825 and went to Australia in 1845, for his health. There, in addition to being a geographer and physician, he became a prominent botanist. He collected extensively, including a long expedition to northern Australia in 1855-6. There he collected many specimens that turned out to be new to science, including two new melons that he called Cucumis jucundus and C. picrocarpus. The two of them are preserved on this herbarium sheet at Kew.

Fast forward 160 years or so, past a few older taxonomic revisions, and you get to one based on molecular analysis that splits the two previously recognized species of Cucumis in Asia, the Malesian region and Australia into 25 species. By this analysis Australia harbours seven species of Cucumis, five of them new to science. C. picrocarpus is one of the two previously recognized species, and the molecular analysis reveals that it is actually the closest wild relative of the cultivated melon, C. melo.

So what? Quite apart from the necessity to call things by their correct names, cultivated melons are besieged by many economically important pests and diseases. It seems likely that, as so often, resistance will come from a wild relative. Which means it is good to know exactly which plant is the closest wild relative. So what’s the status of C. picrocarpus in the wild? I have no idea, alas. I couldn’t find any entries in GBIF (possibly because they are all subsumed under C. melo) and with Luigi gone temporarily to ground I’m not sure where else to look. It seems a fair bet that it might need protection, although I’d be delighted to be wrong.

- Telford, I., Schaefer, H., Greuter, W., & Renner, S. (2011). A new Australian species of Luffa (Cucurbitaceae) and typification of two Australian Cucumis names, all based on specimens collected by Ferdinand Mueller in 1856 PhytoKeys, 5 DOI: 10.3897/phytokeys.5.1395

Melon breeders in general (specially the Australians) would value this information and could round up some support from institutions with the mandate to protect genetic resources, specially of cultivated species.

Screening C. picrocarpus against the pests, stresses and diseases that plague C. melo can be a productive subject for research.

But first, it is required to find, map and collect the populations that are in the wild.

Old specimen is wild crop relative of cucumis melo we have same in Iraq but age is 1946

it is damage by the last war

C. picrocarpus grows on black soil floodplains on the Darling Downs. It is very rare and seems to prefer slightly disturbed sites in remnant grasslands. I suspect it is commonly overlooked though and may often be mistaken as an introduced weed species. Incidentally, C. picrocarpus is not immune from pests and diseases. When brought into cultivation it seems to be attacked by many of the same pathogens and insects. It is perhaps more hardy to them, but this would require more study.