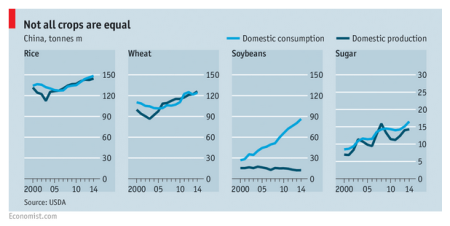

There’s a chart in last week’s issue of The Economist that really got my attention. Here it is:

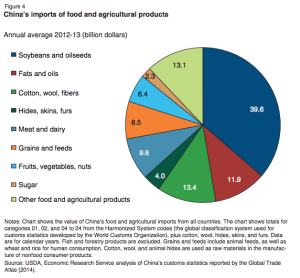

What in tarnation has been happening to soybean production in China? It looks really bad, especially compared to what’s happening to the other crops. And it’s important. Soybeans are now a big proportion of overall food imports.

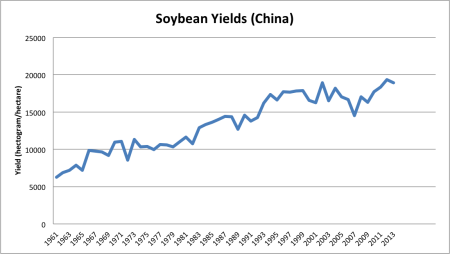

So is it that Chinese farmers are just growing less of the crop? Well, FAOStat says no, it’s that yields have been stagnating of late:

But this is a problem that, for example, the US and Brazil seem not to be having. It’s not as if Chinese breeders and gene-jockeys aren’t trying. And they have plenty of genetic diversity available. So what’s going on? Maybe one of our readers can explain.

This is not a learned comment but I think it has something to do with the Chinese development of overseas businesses. They pay a mate of mine to grow soy beans in Uruguay, giving him equipment and good guaranteed prices. And we hear today they have further plans for South America – so it’s outsourcing with benefits as it were.

China’s national security strategy is to be self-sufficient in grains, so they won’t outsource that. Soy from elsewhere is cheap and can feed a lot of pigs (more than what is good for them). If international trade would be interrupted, they would be able to get by with less pork, and even eat sweetpotatoes — locally grown pig feed — as they did during the Great Leap Famine.

Yeah but that doesn’t explain the stagnating yields.

I misread your question. I do not think that soybean yield in China is stagnating. It has been growing at a rather linear yearly pace of 23 kg/ha (and 2007 was a really bad year). The growth rate is indeed lower than for Brazil (38 kg/ha), but not far off from the USA (27 kg/ha) — but US soybean yields are 1 ton/ha higher. So soybean yields in China are lower than one might expect. Why, indeed, would that be?

One of your readers (me) has already explained this (and earlier Anderson, Purseglove, Kloppenburg, and Cock and Jennings). Introduced crops (soybean in the Americas and everything else, in particular plantation crops) do better. The reason is the absence (or scarcity) of co-evolved pests and diseases in Centres of Origin. That is the reason, or a lot of it “why that should be” — Robert’s question. It makes sense, as a major soy importing nation, for China (and Japan and lots more) to promote soy production elsewhere – it is easier and more profitable than at home. If Saudi Arabia wants cheap wheat send me off to Australia to buy 1 million ha. of wheat land and save all that cash spent on irrigated wheat at home. And everyone funding `native and underutilized species’ should accept that native species have lots of native pests and diseases: not fair of poor farmers..

Thanks, Dave. Always good to hear it again.

This makes sense. Does it hold true for maize and potatoes? much better yields in old world as opposed to new?

So, do the Chinese follow the same approach of outsourcing and then importing their native crops with other crops like rice (apparently not according to the same Economist source!), citrus, tea, peaches, etc.?

Paul: No. Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa each have 70% of their crop production from introduced crops. Not so Asia. The reason is that rice – from Asia – is the very predominant crop in Asia and wins the fight against the introduced crops. Curiously, most rice in Asia is grown as a monoculture – a problem for agroecologists who seem not to like monocultures. For tree and plantation crops the norm is production away from Centres of Origin – tea in Kenya, peaches in California etc.