The Sacramento Bee has a nice piece by David Boulé 1 about the history of the ‘Washington’ Navel Orange in California, the world’s second most common orange variety (after ‘Valencia’).

Navel oranges have been known in Spain and Portugal for centuries. They made their way from there to Brazil, where, in Bahia, a seedless and easy-to-peel variety of great taste and color was discovered. It was probably a sport (mutant) from the Portuguese variety ‘Umbigo’, which is said to be described in the Histoire naturelle des orangers by Risso and Poiteau (you can get your own copy). I could not find it in that book, but I did enjoy Poiteau’s botanical drawings, like this one 2:

From Bahia the tasty navel went to Australia in 1824 and to Florida 3 in 1835, and from Australia to California. But the introduction that led to adoption of the name ‘Washington’ and to its commercialization in California and around the world occurred in 1870, when William O. Saunders of the USDA received twelve trees from Bahia (twigs in an earlier shipment had been dead on arrival). They were planted in a greenhouse in Washington D.C. and propagated for distribution 4.

On 10 December 1873, Eliza Tibbets of Riverside, southern California, traveled by buckboard to Los Angeles to pick up two of these trees, delivered by stagecoach from San Francisco 5. Their fruits won first price at a citrus fair in 1879, and the ‘Washington’ navel spread rapidly after that — there was a citrus gold rush going on after the recent completion of the transcontinental railroad, which allowed selling to markets back east. Oranges were commonly propagated by seed in California, but the seedless ‘Washington’ had to be grafted. The Tibbets sold cuttings at a dollar each, earning as much as $20,000 a year.

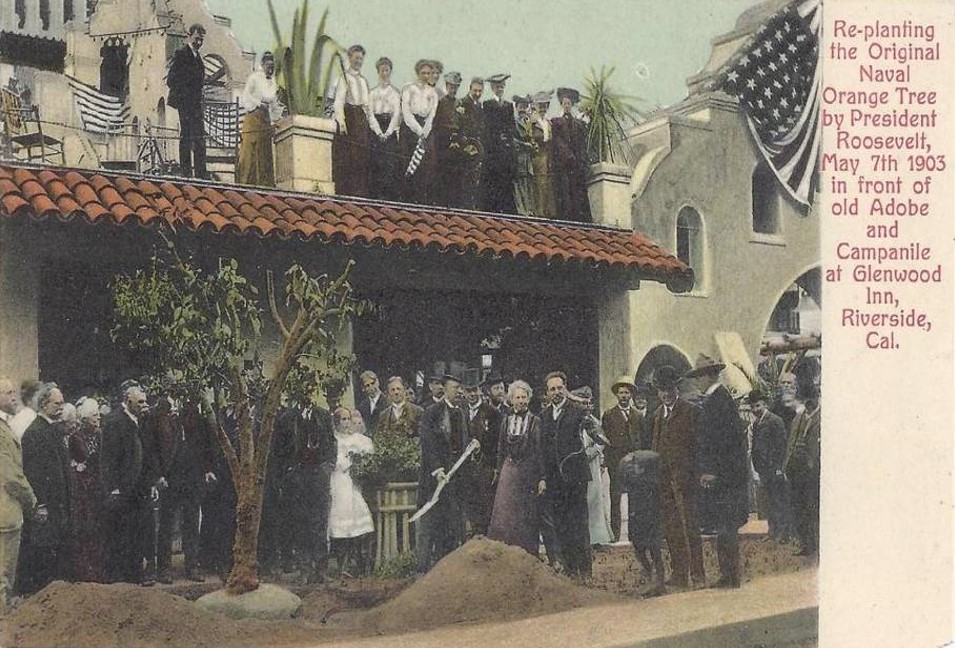

In 1903, one of the original trees was transplanted to a location in front of the Glenwood Hotel in central Riverside, with president Roosevelt shovelling some of the dirt. 6

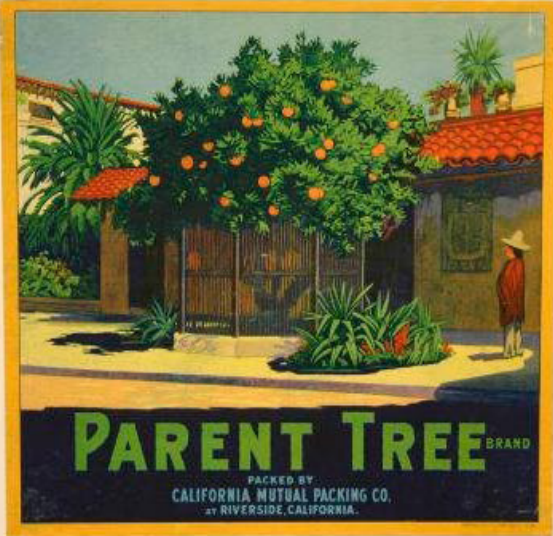

That must have been about here (the name of the hotel was changed to Mission Inn). Alas, the tree died after a couple of years. But it was there long enough to be used in marketing:

The other ‘parent tree’ was planted a couple of miles south of the Glennwood Inn, in Low Park. It is still there, see for yourself, about 145 years old, despite its dire state 50 years ago:

for some years past it has been declining in vigor, and in 1967 seemed unlikely to survive much longer.

The tree is a ‘California historical landmark’ and has this plaque in front of it:

which states that, as of 1920, this was the

most valuable fruit introduction yet made by the USDA.

Was that a fair claim back then? And if so, is it still true? There is some economic analysis here and here.

Riverside does not boast only that tree, it also has the California Citrus State Historic Park. And after you visit that, drive east to the Coachella Valley to see the dates that were introduced a few decades later. 7

- Author of ‘The orange and the dream of California‘. You can see him speak about oranges here.

- Perhaps that is the one, it looks a lot like the navels from my backyard.

- Where it tends to produce poorly and the fruit is generally large, coarse-textured, and of poor quality. It is clearly not well adapted to hot, semitropical climates

- http://websites.lib.ucr.edu/agnic/webber/Vol1/Chapter4.html, http://www.citrusvariety.ucr.edu/citrus/parent_1241B.html, http://www.citrusroots.com/downloads/History-and-Development-of-the-California-Citrus-Industry-2014.pdf

- Where they had arrived after a four weeks train trip from Washington D.C.

- Here is the photograph that was used to make this postcard.

- Like these, which were reintroduced to Morocco, the Washington navel was reintroduced to Brazil after they had been wiped out there.

Thanks for this interesting story. A few months ago I visited the San Gabriel Mission and discovered its importance in the cultivation of oranges in California. You might already know this article.

Best wishes, Emanuela