When I saw news stories a short while back about a new peanut variety called Tifguard, famous for having resistance to both peanut root-knot nematode and tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), the main question I had was where the resistance(s) came from. So I consulted our resident peanut expert, and it turns out that the nematode resistance gene in Tifguard came from the variety COAN. Which in turn got it from the wild relative Arachis cardenasii. And by conventional breeding, no less.

Although saying that glosses over the fact that Charles Simpson‘s introgression programme at Texas A&M sometimes involved making more than a thousand meticulous interspecific crosses just to get a single seed. Nobody ever said using crop wild relatives in breeding programmes was easy! Anyway, this is a truly exemplary case of what can be done to incorporate genes from crop wild relatives into improved cultivars using “conventional” breeding methods.

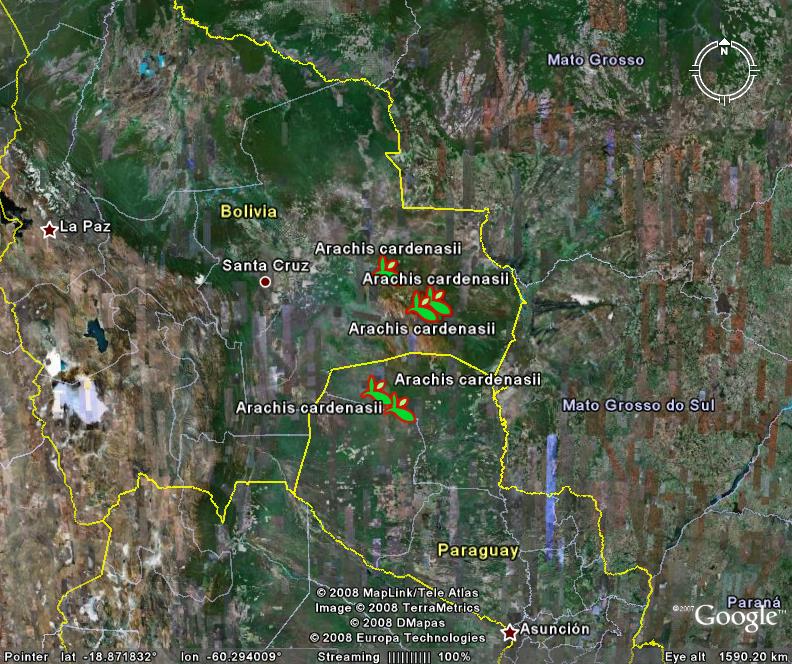

Not much A. cardenasii in GRIN or SINGER. ((Although I’m sorry to say I wasn’t actually able to get SINGER to give me much more than the total number of accessions, and that after a bit of a struggle. Who knows, maybe our resident peanut expert can do something about that. Anyway, do let me know if you have better luck.)) GBIF adds data from a couple of herbaria, but in total we’re talking about no more than about 30 records or so, some of which are no doubt duplicates.

MUCH LATER: Follow-up, with live links!