We expressed some doubts about the Food Desert Locator a few days back. Now it’s Gary Nabhan’s turn.

Important Plant Areas documented

More than 200 areas across North Africa and the Middle East have been identified as wild plant hotspots, a report has revealed. The research lists 207 places which are internationally important for the plants they contain, including 33 in Syria, 20 in Lebanon, 20 in Egypt, 21 in Algeria, 13 in Tunisia and five in Libya.

The report in question is “Important Plant Areas of the south and east Mediterranean region,” 1 just out thanks to IUCN, Plantlife International and WWF, and downloadable for free. The maps are nice, of course, and I hope they’ll be available in digital form in due course, if they are not already. 2 And it is also great to see a list of species with restricted ranges; it includes quite a few crop wild relatives, in particular Allium and Vicia spp.

The report in question is “Important Plant Areas of the south and east Mediterranean region,” 1 just out thanks to IUCN, Plantlife International and WWF, and downloadable for free. The maps are nice, of course, and I hope they’ll be available in digital form in due course, if they are not already. 2 And it is also great to see a list of species with restricted ranges; it includes quite a few crop wild relatives, in particular Allium and Vicia spp.

Ethiopian Agriculture Portal misplaces crop diversity

The Ethiopian Agriculture Portal (EAP) is a gateway to agricultural information relevant to development of Ethiopian agriculture. EAP makes access to information easier because it uses a simple, logically laid-out web interface from which users can access documents on agricultural commodities important to Ethiopia. The collection includes many documents in local languages mainly Amharic…

The intended audiences of the portal are all those engaged in public or private agricultural development endeavors in Ethiopia; including extension, research, higher education, private sector, and other government and non-government stakeholders. In short, it serves national and international entities interested in Ethiopian agriculture as partners in trade, investment, or development.

A very worthy effort, and not badly done. But one is sorry not to see any mention of the Institute of Biodiversity Conservation in Addis Ababa, with it’s storied genebank housing a unique collection of local crop germplasm. And although it is welcome to see, under “Other Resources”, reference to the Domestic Animal Diversity Information System and the Domestic Animal Genetic Resources Information System, one longs for similar exposure for international databases on plant genetic resources, in particular those of the CGIAR Centres, whose data is of course also now available through Genesys.

A very worthy effort, and not badly done. But one is sorry not to see any mention of the Institute of Biodiversity Conservation in Addis Ababa, with it’s storied genebank housing a unique collection of local crop germplasm. And although it is welcome to see, under “Other Resources”, reference to the Domestic Animal Diversity Information System and the Domestic Animal Genetic Resources Information System, one longs for similar exposure for international databases on plant genetic resources, in particular those of the CGIAR Centres, whose data is of course also now available through Genesys.

Nibbles: Cassava, Biopiracy, Neolithic, Potato history, Pollinator conservation

- The pros and cons of biofortified cassava rehearsed for the nth time.

- Scientists accused of biopiracy for the nth time.

- nth genetic study of ancient farmers. Men moved, in a nutshell, women not so much.

- Traditional healers: nth example of a group hard hit by climate change.

- In all above cases, n is a large positive integer.

- Potatoes responsible for about 25% of Old World population increase between 1700 and 1900. Nice maths.

- Learn how to conserve pollinators. If you’re in Rhode Island. But there is an online Pollinator Conservation Resource Center with lots of resources.

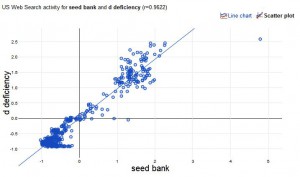

Causation sought between seed banks and vitamin D deficiency

Google has a new thing where you put in a search term and it tells you what other terms showed a similar pattern of search over time since 2004, at least in the US. So of course I played around with it for way too long, but pretty much nothing of interest turned up. Except for one, strange thing. It seems that the time pattern shown by searching for the term “seed bank” is very highly correlated with a number of permutations of the search for “vitamin D deficiency.” Any idea why that should be?

Google has a new thing where you put in a search term and it tells you what other terms showed a similar pattern of search over time since 2004, at least in the US. So of course I played around with it for way too long, but pretty much nothing of interest turned up. Except for one, strange thing. It seems that the time pattern shown by searching for the term “seed bank” is very highly correlated with a number of permutations of the search for “vitamin D deficiency.” Any idea why that should be?