How should farmers deal with rice pests? Spray? Use resistant varieties? Or rely on bio-control ecosystem services?

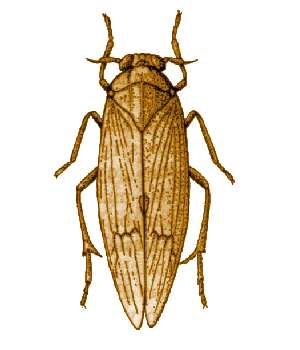

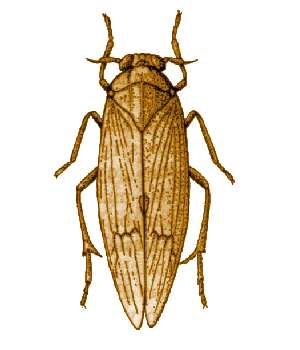

Spraying is what many farmers do, to the detriment of their health and environment. It also makes the pest problem worse. Why? Because pesticides also kill the pests’ natural enemies, such as spiders. So you need to spray again, and again. Until the pests are pesticide resistant. This has led to huge outbreaks of brown plant hopper, like in Indonesia in the 1980s, which only stopped after most pesticides were banned.

Spraying is what many farmers do, to the detriment of their health and environment. It also makes the pest problem worse. Why? Because pesticides also kill the pests’ natural enemies, such as spiders. So you need to spray again, and again. Until the pests are pesticide resistant. This has led to huge outbreaks of brown plant hopper, like in Indonesia in the 1980s, which only stopped after most pesticides were banned.

Use host plant resistance is what many researchers say. Sounds simple enough, and now there are GMO approaches to get that in different forms. Nature magazine recently had a piece about GM approaches to get insect resistant rice in China.

But not everybody agrees. The problem is that some of the major pests occur in large numbers and rely entirely on rice for their life cycle. Strong evolutionary pressure means that these species tend to quickly overcome host plant resistance. In the Nature article, KL Heong calls pest-resistant GM crops a short-term fix for long-term problems caused by crop monoculture and overuse of broad-spectrum pesticides. “Pests thrive where biodiversity is at peril, instead of genetic engineering, why don’t we engineer the ecology by increasing biodiversity?”

This week, in a letter to the editor of Nature, Settele, Biesmeijer and Bommarco also make a case for ecological engineering: the design and construction of ecosystems.

The nice thing about tropical rice is that there is not that much engineering needed to keep pests under control. This is my understanding of how it works:

- Rule #1: do not kill the beneficial insects (avoid pesticides).

- Rule #2: help the beneficial insects. For example, by providing ample organic matter to fields, you increase the population of harmless insects and with that the population of generalist predators (see below).

- Rule #3, maintain a diverse landscape around the rice fields to support useful insects, such as parasitoids that, as adults, need nectar from flowering plants.

William Settle and colleagues studied rice bugs in Indonesia and summed their findings up like this:

By increasing organic matter in test plots we could boost populations of detritivores and plankton-feeders, and in turn significantly boost the abundance of generalist predators. We also demonstrated the link between early-season natural enemy populations and later-season pest populations by experimentally reducing early-season predator populations with insecticide applications, causing pest populations to resurge later in the season.

Irrigated rice systems support high levels of natural biological control that depends on season long successional processes and interactions among a wide array of species. Our results support the conservation of existing natural biological control through a major reduction in insecticide use, and an increase in habitat heterogeneity.

While it seems obvious that relying on and strengthening ecosystem services is the way to go, this is not what is happening. The brown plant hopper is coming back as a major problem, particularly in Vietnam and China. The response? Breeding & Spray, baby, spray.

It is tricky to generalize about agriculture and pests. There are always exceptions and special circumstances. And what if someone can make a rice plant that is truly immune to stem borers and plant hoppers. Well, some other insects would go after the available resources, but it could certainly be beneficial. Also, the biodiversity of insects in tropical rice fields, such as in Indonesia, is much higher than in China (probably largely because of the general relation between latitude and diversity, but perhaps also because of excessive pesticide use in China). So perhaps biocontrol ecosystem services are not as effective in China as in more tropical areas. We should find out.

And we should get serious about ecological engineering.

And not just in rice. Take this article that appeared in this week’s PNAS. It describes the need for maintaining landscape diversity in the USA, to support aphid control in soybeans by ladybugs.

Spraying is what many farmers do, to the detriment of their health and environment. It also makes the pest problem worse. Why? Because pesticides also kill the pests’ natural enemies, such as spiders. So you need to spray again, and again. Until the pests are pesticide resistant. This has led to huge outbreaks of brown plant hopper, like in Indonesia in the 1980s, which only stopped after most pesticides were banned.

Spraying is what many farmers do, to the detriment of their health and environment. It also makes the pest problem worse. Why? Because pesticides also kill the pests’ natural enemies, such as spiders. So you need to spray again, and again. Until the pests are pesticide resistant. This has led to huge outbreaks of brown plant hopper, like in Indonesia in the 1980s, which only stopped after most pesticides were banned.