![]() Why do some trees have red leaves in autumn? Yellow leaves are easy to explain; the breakdown of chlorophyll exposes yellow carotenoids that were there all along but masked. Red, however, is the result of anthocyanins, which the plant manufactures specifically. That imposes a cost, so evolutionary biologists have long looked for the corresponding benefit. One theory is that the red pigments protect the leaf from damage by light, especially at low temperatures, giving the tree more time to absorb and store nutrients from the leaves it is about to drop. Evidence on that is contradictory and inconclusive. Another is that the red pigment is actually a signal to insects or some other creatures that make use of the trees.

Why do some trees have red leaves in autumn? Yellow leaves are easy to explain; the breakdown of chlorophyll exposes yellow carotenoids that were there all along but masked. Red, however, is the result of anthocyanins, which the plant manufactures specifically. That imposes a cost, so evolutionary biologists have long looked for the corresponding benefit. One theory is that the red pigments protect the leaf from damage by light, especially at low temperatures, giving the tree more time to absorb and store nutrients from the leaves it is about to drop. Evidence on that is contradictory and inconclusive. Another is that the red pigment is actually a signal to insects or some other creatures that make use of the trees.

Turns out that the second is correct. Over-wintering aphids avoid trees with red leaves and do worse in the spring if forced to grow on those trees.

Marco Archetti, late of Oxford University and now at Harvard, has a paper ((Archetti, M. (2009). Evidence from the domestication of apple for the maintenance of autumn colours by coevolution Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2009.0355)) that is forehead-smitingly clear and convincing, which is of additional interest here because it uses agricultural biodiversity, field genebanks and wild relatives as the natural experiments with which to test the hypothesis.

First off, aphids do avoid red-leaved trees. Archetti counted the number of Dysaphis plantaginea, which commonly lays eggs on apple to overwinter, on trees at Brogdale, the UK’s apple field genebank . Red-leaved varieties attracted fewer aphids than green-leaved varieties, which in turn were less attractive than yellow-leaved varieties. Of course, it might be that aphids just don’t see red leaves all that well. Perhaps the red leaves, noticeable though they are to us, are effectively camouflaged. To test this Archetti placed virgin female aphids in cages on the fresh green leaves of Brogdale varieties that had been planted three years previously at a nearby community orchard. Then he waited to see how many produced the winged adults that disperse in the summer. On red-leaved varieties, 29% of the females produced winged adults. On green- and yellow-leaved varieties (which did not differ) almost 60% of the females produced winged adults. Aphids are not as fit on red-leaved trees.

First off, aphids do avoid red-leaved trees. Archetti counted the number of Dysaphis plantaginea, which commonly lays eggs on apple to overwinter, on trees at Brogdale, the UK’s apple field genebank . Red-leaved varieties attracted fewer aphids than green-leaved varieties, which in turn were less attractive than yellow-leaved varieties. Of course, it might be that aphids just don’t see red leaves all that well. Perhaps the red leaves, noticeable though they are to us, are effectively camouflaged. To test this Archetti placed virgin female aphids in cages on the fresh green leaves of Brogdale varieties that had been planted three years previously at a nearby community orchard. Then he waited to see how many produced the winged adults that disperse in the summer. On red-leaved varieties, 29% of the females produced winged adults. On green- and yellow-leaved varieties (which did not differ) almost 60% of the females produced winged adults. Aphids are not as fit on red-leaved trees.

So it looks like the coevolution explanation has a lot going for it. Apple trees make red pigments that signal to aphids that the tree is a less than desirable host. Those aphids that do select red-leaved trees don’t do as well in the spring as those that avoid red-leaved trees. Without knowing exactly what it is about the host that leaf colour signals, we can see that the tree selects against aphids that choose it.

As Archetti drily observes:

The ideal test of the coevolution hypothesis would be to let populations of the same species evolve with and without insect pests for many generations: if autumn colours are a signal to insects, we would expect red coloration to be lost in the populations evolving without insects. This experiment would take too long to perform, but a similar test was actually initiated ca 2000 years ago with the domestication of fruit trees.

A trip to Central Asia is clearly in order. Among wild apple populations in Kyrgystan and Kazakhstan, in excess of 60% of the trees have red leaves in autumn. At Brogdale, just 2.8% of the 2170 cultivars ((Why does the Brogdale site list only 1893?)) have red leaves in autumn. And, pleasingly, cultivated varieties in Central Asia also tend not to produce red leaves; 39% turn red in autumn. There’s a similar pattern at other field collections around the world, so the loss of red colouration under domestication is not simply a reflection of growing conditions.

Why are red-leaved trees signalling? Theory suggests that are either more vigorous (and so can afford the signal) or are equally vigorous but have a greater need to avoid aphids. The US national apple collection has evaluated the vigour of trees on a standard rootstock. Red-leaved varieties do not differ from green- or yellow-leaved ones.

Why might trees need to avoid insects? Sap-suckers like aphids are known to transmit diseases, perhaps the most devastating of which is fire blight. And lo! US cultivars that turn red in autumn are much, much more susceptible to fire blight, suggesting that being red protects them from fire blight by keeping aphids away. (Varieties from Central Asia are highly resistant to fire blight, regardless of leaf colour, perhaps because fire blight originated in the US and has not yet adapted to wilder types.)

That’s almost the whole story. The final points are that red-leaved cultivars have smaller fruits than green- and yellow-leaved types. Archetti interprets this as an indication of less efficient selection: “Because increasing fruit size has been the main selective pressure under domestication, varieties that have undergone less efficient selection are expected to have smaller fruits.” Fruits described as “astringent” are also more common among varieties that turn red, and Central Asian varieties in the US genebank are more astringent than green- and yellow-leaved varieties, but no different from red-leaved varieties. “Since apple varieties have been selected against astringent flavour, this also supports the idea that cultivars with red leaves are more similar on average to their wild ancestors.”

And there you have it. Red leaves coevolved with disease-spreading insects because

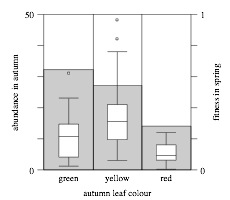

(i) Aphids are more abundant on green and yellow autumn leaves than on red leaves.

(ii) Aphids have higher fitness in spring on trees with green and yellow autumn leaves than on trees with red leaves.

(iii) Autumn colours are common in wild varieties but rare under domestication.

(iv) Only varieties with high susceptibility to ï¬re blight have red autumn leaves.

(v) Varieties with red autumn leaves have smaller fruits and more astringent taste.

Best yet, these conclusions make similar predictions for other domesticated trees, for example apricot and walnut that turn colour in the fruit forests of Central Asia but not in orchards of domesticated cultivars. Different pests and diseases are almost certainly involved, but the selective pressures remain the same.

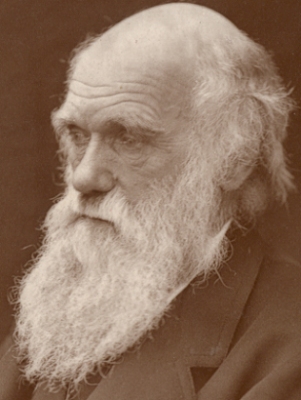

Given that he wrote an entire book on The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, Charles Darwin offers us a rich seam to mine. ((Made easier by the existence of

Given that he wrote an entire book on The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication, Charles Darwin offers us a rich seam to mine. ((Made easier by the existence of  Despite the tomato’s presence along the Atlantic Seaboard and the Gulf Coast, its introduction and adoption in the interior areas of southern states appear to have been delayed. In Salem, North Carolina, tomatoes were not sown until 1833, when a gentleman from South Carolina sent seeds to an “old Mr. Holland.” At that time no one had tasted tomatoes, and scarcely any one had heard of them. Similar late arrivals were probably common for other rural areas of the South. In 1820 Phineas Thornton published a thorough inventory of the kitchen garden plants within a twenty-mile radius of Camden, South Carolina, and made no mention of the tomato. His Southern Gardener and Receipt Book, published twenty years later, included instructions for cultivating and preparing tomatoes for the table, which suggests that they were introduced in Camden sometime between 1820 and 1840.

Despite the tomato’s presence along the Atlantic Seaboard and the Gulf Coast, its introduction and adoption in the interior areas of southern states appear to have been delayed. In Salem, North Carolina, tomatoes were not sown until 1833, when a gentleman from South Carolina sent seeds to an “old Mr. Holland.” At that time no one had tasted tomatoes, and scarcely any one had heard of them. Similar late arrivals were probably common for other rural areas of the South. In 1820 Phineas Thornton published a thorough inventory of the kitchen garden plants within a twenty-mile radius of Camden, South Carolina, and made no mention of the tomato. His Southern Gardener and Receipt Book, published twenty years later, included instructions for cultivating and preparing tomatoes for the table, which suggests that they were introduced in Camden sometime between 1820 and 1840.