- Make way for Dovyalis hebecarpa, aka the Ceylon gooseberry, your new favourite superfood for the week.

- US$6.5 million to breed better cucurbits. Maybe.

- Rise and fall of agrarian states influenced by climate volatility. Those who do not understand history etc.

- Bioversity urges crop wild relatives to avoid the fate of the dodo.

- Name that grape! An extraordinary online resource for Italian ampelography.

Brainfood: Forage diversity, Chinese cherry, Meta-diversity, Sunflower ecogeography, Lima bean domestication, Dog breeding, Goat ethnogenetics, Pigs vs chickens

- Complementary effects of species and genetic diversity on productivity and stability of sown grasslands. Species diversity good for total production, genetic diversity good for regular production throughout the year, regardless of water. And more, and more.

- Genetic Diversity and Population Structure Patterns in Chinese Cherry (Prunus pseudocerasus Lindl) Landraces. Perhaps 2 domestication sites.

- Inter-individual variation promotes ecological success of populations and species: evidence from experimental and comparative studies. More diverse populations are less vulnerable to environmental changes, more stable in population size, less extinction prone, have better establishment success and larger ranges, especially under stress.

- Ecogeography and utility to plant breeding of the crop wild relatives of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Many close relatives of the crop in extreme environments.

- Domestication of small-seeded lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) landraces in Mesoamerica: evidence from microsatellite markers. Two domestications events. Maybe.

- Trends in genetic diversity for all Kennel Club registered pedigree dog breeds. Popular sires have made for a lot of inbreeding, but this has been getting better of late.

- The N’Dama dilemma: ethnogenetics and small ruminant breed dynamics in the tsetse zone, The Gambia. Saving the name is not enough.

- The Pig and the Chicken in the Middle East: Modeling Human Subsistence Behavior in the Archaeological Record Using Historical and Animal Husbandry Data. Chickens replaced pigs in the first millennium Middle East because they were smaller and more efficient. Oh, and eggs.

Brainfood: Wild wheat breeding, Global pea breeding, Old Swedish peas, Prolific Chinese pigs, Genomics & CC, Veggies & food security, Agrobiodiversity use, Land use double, Agrobiodiversity use

- Genealogical analysis of the use of aegilops (Aegilops L.) genetic material in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). 1350 varieties in 50 years, involving mainly 3 wild species, the proportion of total releases using wilds steadily growing. But many pedigrees may be wrong. Not to mention the taxonomy.

- Pea. In the Grain Legumes volume of the Handbook of Plant Breeding, that is. Two cultivated species, >70,000 accessions, 28+ national and international collections, yield gains of 2% per year over past 15 years, plus good progress in lodging, disease resistance and seed visual quality and modest improvement in abiotic (heat, frost, salinity and herbicide resistance) stress resistance. Genome on the way.

- Diversity in local cultivars of Pisum sativum collected from home gardens in Sweden. Add about 70 to that number of genebank accessions.

- Genetic diversity and population structure of six Chinese indigenous pig breeds in the Taihu Lake region revealed by sequencing data. They are indeed pretty much 6 breeds. The most prolific in the world too, apparently.

- Global agricultural intensification during climate change: a role for genomics. ‘Course there is.

- The Role of Vegetables and Legumes in Assuring Food, Nutrition, and Income Security for Vulnerable Groups in Sub-Saharan Africa. ‘Course there is.

- Drivers for global agricultural land use change: The nexus of diet, population, yield and bioenergy. Livestock, in a word.

- Resolving Conflicts between Agriculture and the Natural Environment. You need “policies dedicating high-quality habitat towards nature conservation, while encouraging intensive production on existing farmland with stringent limits on environmental impacts.” But see above; although they do say in the previous paper that the trend has been slowing lately.

- Using our agrobiodiversity: plant-based solutions to feed the world. “…the preservation and development of existing agrobiodiversity has not been given sufficient attention in the current scientific and political debates concerning the best strategy to keep pace with global population growth and increasing demand for food.”

Wheat that goes around, comes around

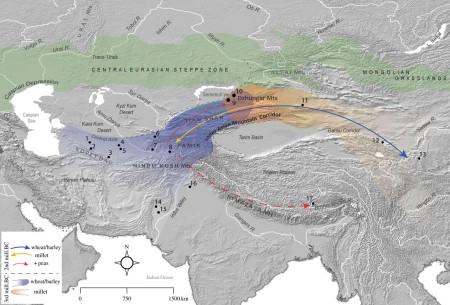

![]() There’s lots of fascinating material in Robert Spengler’s new review paper on Agriculture in the Central Asian Bronze Age. 1 This map of the region comes from an earlier paper of his, but sets the scene nicely.

There’s lots of fascinating material in Robert Spengler’s new review paper on Agriculture in the Central Asian Bronze Age. 1 This map of the region comes from an earlier paper of his, but sets the scene nicely.

The thesis of the latest paper is that the conventional model of mixed agropastoralism in Central Asia gradually becoming typical nomadic pastoralism needs to be rethought. In fact, Spengler says, after looking in detail at the archaeological evidence, the mixed pastoral economies of the Bronze Age, with their distinctive package of crops derived from both further east and west in place by 2500 BC, actually intensified into the Iron Age. The result was “irrigated agriculture, sedentary villages, and a drastically altered anthropogenic landscape.”

I may come back to that in a later post, but here I want to focus on what I learned about wheat. I knew that the Green Revolution was based in large part on the use of Rht genes from a Japanese wheat called Norin 10. These genes cause dwarfing, and allow the wheat plant to divert energy into the grain rather than the straw. Yields shot up in places like India, and the Borlaug legend was born.

What I didn’t know is that there was so-called “Indian dwarf wheat” in Afghanistan, Pakistan and northern India before the Green Revolution, characterized by

…dense strong culms and erect blades, a condensed spike which expresses with short awns, glumes, and a hemispherical grain. In addition, it has increased tillering and a reduced rate of lodging…

All of the wheat found in Bronze Age Central Asia seems to have been of this type too, as far as one can tell by comparing archaeobotanical remains with herbarium and genebank material. And similar material turns up in sites in Japan and Korea a millennium and more later. Spengler is circumspect, asking for genetic studies, but it is certainly an intriguing possibility that

…pre-Harappan farmers in India bred a phenotype that would later alter agriculture globally.

Nibbles: Oyster wars, Bitter veggies, Saffron, Ag & development, Cannabis taxonomy, Mold evolution, Svalbard & ICARDA, Blueberry taste

- The land sparing vs sharing debate encapsulated in a controversy over San Francisco oyster farming.

- Bitter is good.

- BBC’s Farming Today on saffron in England, among other things.

- Want sustainable development? Invest in agriculture.

- Growing weed: here comes the science.

- “When you chew on a Camembert rind, you’re eating a solid mat of mold.” And probably GM to boot.

- Why do I sound so totally unprepared?

- Breeding better blueberries.