- Pepe gets a prize from a queen.

- The Princess of the Pea gives no prizes, though.

- Oldest farming village in a Mediterranean island found on Cyprus. No royalty, alas.

- The Emperor of Agricultural Statistical Handbooks is out. Oh, and the online source of the raw data has just got some new clothes.

- Fish are in trouble. Well, not all. Kingfish, queenfish, king mackerel and emperor angelfish all unavailable for comment.

- No royalty connected with these beautiful pictures of Asian fish either. Does a former Dutch consul count?

- Quite a crown on this wild goat.

- The Royal (geddit?) Botanic Gardens Kew’s Breathing Planet Campaign: The Video.

- ICIMOD on the role bees (including, presumably, their queens) in mountain agriculture.

Nibbles: Yams, Aroids, Shattering gene, Panicoid genomes

- Improving yams at IITA.

- Improving aroids the world over.

- Parallel evolution in the domestication of cereals. Will it help to improve them?

- Foxtail millet helps with switchgrass genome assembly. And, one supposes, improvement.

Nibbles: Quinoa, Chilean landraces, Planetary sculptors, Offal, Eels, Grand Challenges in Global Health, ILRI strategy, Artemisia, Monticello, Greek food, Barley, Rain

- The commodisation of quinoa: the good and the bad. Ah, that pesky Law of Unintended Consequences, why can we not just repeal it?

- No doubt there are some varieties of quinoa in Chile’s new catalog of traditional seeds. Yep, there are!

- Well, such a catalog is all well and good, but “[o]ne of the greatest databases ever created is the collection of massively diverse food genomes that have domesticated us around the world. This collection represents generation after generation of open source biohacking by hobbyists, farmers and more recently proprietary biohacking by agronomists and biologists.”

- What’s the genome of a spleen sandwich, I wonder?

- And this “marine snow” food for eels sounds like biohacking to me, in spades.

- But I think this is more what they had in mind. Grand Challenges in Global Health has awarded Explorations Grants, and some of them are in agriculture.

- Wanna help ILRI with its biohacking? Well go on then.

- Digging up ancient Chinese malarial biohacking.

- Digging up Thomas Jefferson’s garden. Remember Pawnee corn? I suppose it’s all organic?

- The Mediterranean diet used to be based on the acorn. Well I’m glad we biohacked away from that.

- How barley copes with extreme day length at high latitudes. Here comes the freaky biohacking science.

- Why working out what is the world’s rainiest place is not as easy as it sounds. But now that we know, surely there’s some biohacking to be done with the crops there?

Rewarding excellence in Indian rice breeding

India’s Directorate of Rice Research has just recognized the Paddy Breeding Station of Tamil Nadu Agricultural University (TNAU) as the best rice breeding station among India’s 107. The Vice-Chancellor of the university said that:

“The landmark varieties that have been developed through Pure Line Selection by this station triggered the growth of rice production in the State. The first variety — GEB 24 (Kichili Samba) — released during 1921 played a significant role in the development of rice cultivars over the years, not only in India, but world-wide.”

With help from the irrepressible Nik and his local version of IRRI’s all-knowing germplasm database we can actually kind of quantify that. It turns out that out of the 11 IRRI releases in 2011 (IR155-165), only IR157 (an irrigated japonica) doesn’t have GEB 24 in its pedigree. Just for that, it would seem to be a very well-deserved award. But I’m also told they helped IRRI build up its collection in the early days.

What about the other direction of use, though? Well, IR8 starts to feature, by itself, in the pedigrees of TNAU varieties in the early 70s (e.g. in CO38 and CO40), then by the early 80s there are 5 IRRI lines involved in the development of CO43. But by the 90s there are a couple dozen IRRI lines in the pedigree of CO47. So the flow of germplasm has been two-way.

In more ways than one. Apparently, IRRI are in the process of restoring to TNAU some of their CO varieties, which they had lost for one reason or another, but had taken the precaution of sending to Los Baños. Good collaboration all around. Great to see the achievements recognized in the popular press, if not necessarily the collaboration. But then that’s what we’re here for.

LATER: Further delving into the database by our friends at IRRI reveals that TNAU sent material quite regularly to IRRI from 1961 to 1987, with a peak of 952 accessions in 1978. But “only 40% of TNAU’s CO varieties conserved in the IRRI genebank came directly from TNAU. 30% came via CRRI and 30% via other organizations. TNAU obviously shared their material widely.”

The how and why of indicators of agricultural biodiversity

![]() Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that one crop variety does disappear every single day. The question still remains: does it matter? After all, the variety that was just lost yesterday might be very similar to one that’s still out there today. That’s part of the reason why a group of French researchers has just come up with “A new integrative indicator to assess crop genetic diversity,” which is the title of their paper in Ecological Indicators. 1

Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that one crop variety does disappear every single day. The question still remains: does it matter? After all, the variety that was just lost yesterday might be very similar to one that’s still out there today. That’s part of the reason why a group of French researchers has just come up with “A new integrative indicator to assess crop genetic diversity,” which is the title of their paper in Ecological Indicators. 1

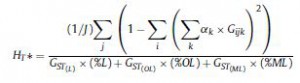

Christophe Bonneuil and his co-workers thought that, given the data, they could come up with something more powerful and more widely applicable than richness (i.e. the number of different varieties) or the standard diversity indicators (i.e. various combinations of richness and evenness). So they started with number of varieties, but then they factored in the relative extent to which each was grown in their study area, the departement of Eure-et-Loire in France (which is the evenness bit), how genetically distinct each was (which is the bit which addresses the pesky question of how different the variety that disapeared today is from all the other ones left behind), and how much genetic diversity there was inside each.

They got the data on genetic differences among varieties by comparing genebank samples of all the wheat types grown in Eure-et-Loire from 1878 and 2006 at 35 microsatellite loci, and data on acreage of each variety at different points in time from various archival sources. Internal genetic diversity was set at one of three values derived from the literature, depending on whether the variety was a landrace, an old commercial line or a modern pure line.

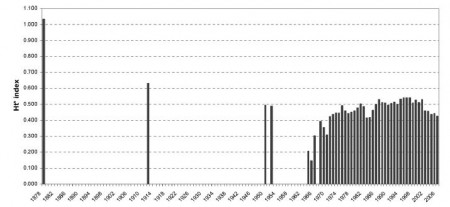

They put all that together into this monster indicator of allelic diversity in the landscape,

and then calculated it for different times periods, and got this:

That shows a decrease in diversity as landraces are replaced with modern varieties, but, interestingly, something of a resurgence after the mid-1960s, as more diverse germplasm is introduced into breeding programmes. The indicator has been on a downward trend just lately, as the genetic relatedness of the most frequent varieties has increased. 2 Overall, it’s maybe a 50% drop since 1878. Not entirely dissimilar to the iconic 75% figure, and at least this wasn’t plucked out of thin air.

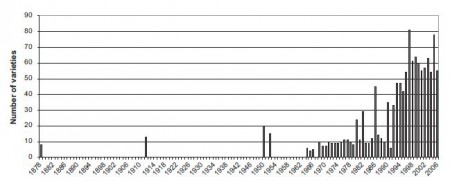

Interesting enough, but check out the trend in number of varieties over the same period:

Totally different. Pretty much an upward trend, albeit with some stuttering. Certainly no evidence from these data of massive erosion of diversity. Maybe the findings of Jarvis et al. (2008) that simple richness can be a useful indicator of diversity should be applied with caution if you’re not just dealing with landraces.

But how significant is it really that the value of this particular indicator of diversity, for all its fanciness, has decreased? Has anyone actually suffered as a result? I don’t know, but a second paper I came across this week suggests how one could find out. Roseline Remans and others associated with the Millennium Villages Project have a study out in PLoS ONE which adds yet another — different — nuance to diversity. 3 Their index considers not just how many different crops are grown on a farm, but also how different they are in their nutritional composition. Think of it as the nutritional analogue of the inter-varietal genetic diversity term in the French indicator. The more different in nutritional composition two crops are, the more complementary they are to local diets, the more important it is that both are there, the higher the resulting “functional” diversity index. And in fact the authors did find a positive relationship between their diversity indicator and nutritional status, at least at the village level.

Easy to imagine (though perhaps less easy to actually implement) a further refinement of Bonneuil et al.’s indicator which additionally integrates nutritional data, to yield an indicator of crop genetic and functional diversity. And, of course, once you have such a super-indicator, it might actually be possible to reward people on the basis of their success in maintaining it at high levels. Which, as it happens, is the subject of yet another paper I happened across last week. 4 But maybe that’s a paper too far for now. 5