Sorry for the slow blogging, but I’m ill in bed and Jeremy is travelling. But none of that will stop us from wishing you all a happy International Women’s Day!

Radicchio diversity

Following in Luigi’s footsteps, the botanic gardens at Padua beckoned. The oldest botanic gardens in the Old World (Wikipedia is wrong; the New has older) they have operated continuously in the same place since 1545. A freezing February day was not ideal to see plants, and precious few of the labels denoted anything directly edible as food. I was not, however, entirely disappointed, for in a sunny bed in the lee of a building was a display of perhaps the region’s most famous crop: radicchio.

The picture above shows an old local variety, Variegato di Castelfranco, and Otello, a modern cultivar. Which, naturally, sent me scurrying to discover more about their history and breeding. There isn’t, actually, a huge amount. One study, of which I’ve seen only the abstract, examined DNA diversity of the five major types. Turns out that if you compare pooled bulk DNA from six individuals of each type, the different types are easy to distinguish. If, on the other hand, you look at DNA from individuals, the distinctions disappear. The variation within a single type is much greater than the variation among the different types. This, the researchers say, indicates that the types have maintained their “well-separated gene pools” over the years. An earlier paper (available in full) had come to a similar conclusion about the populations, with what seems like an ulterior motive: 1

The molecular information acquired, along with morphological and phenological descriptors, will be useful for the certification of typical local products of radicchio and for the recognition of a protected geographic indication (IGP) mark.

And lo, it came to pass. Four types (I think early and late Rosso di Trevisos are included in one designation) got their Protected Geographical Indication in 2008 and 2009. That’s late — tardivo — in the photograph below.

Gebisa Ejeta on his life journey, and life’s work

2009 World Food Prize Laureate Gebisa Ejeta makes the point in this inspiring video that even more important than his work in finding a genetic mechanism for Striga resistance in sorghum was that he didn’t stop there, but strived to get his new varieties into farmers’ fields, so that they could actually do some good.

The Economist mentions crop wild relatives!

The Economist’s special feature on feeding the world pretty much pushed all the expected buttons. The challenges are great: food supplies probably have to increase by 70% in the next 40 years. More inputs — land, irrigation, fertilizers — is not exactly off the table as a strategy, but won’t be nearly enough. Technology is what we need: in particular plant breeding, though also intensification of livestock keeping. It won’t be easy: that 70% increase in production translates into things like a doubling of the growth rates in yields of wheat, to >2% per year. And climate change will make what would have been a difficult task at the best of times even harder. The growth rate in wheat yield will have to be achieved in the face of a likely 20% fall caused by a 2ºC increase in global temperatures. But advances in genomics make all this possible, although the way this was presented was somewhat eccentric, I thought:

…the change likely to generate the biggest yield gains in the food business—perhaps 1.5-2% a year—is the development of “marker-assisted breeding”—in other words, genetic marking and selection in plants, which includes genetically modifying them but also involves a range of other techniques.

Also predictable was the trotting out of the dreaded 75% figure for loss of agrobiodiversity:

Three-quarters of all the world’s plant genetic material may have gone already, mostly by habitat destruction, says Pasquale Steduto of the FAO, and more is going every day.

What was less expected, at least to me, was a final, brief but nevertheless welcome, section on the importance of micronutrients, which even suggested that technology might not be sufficient on its own:

Better nutrition, in short, is not a matter of handing out diet sheets and expecting everyone to eat happily ever after. Rather, you have to try a range of things: education; supplements; fortifying processed foods with extra vitamins; breeding crops with extra nutrients in them. But the nutrients have to be in things people want to eat.

Most unexpected, however, and most welcome, were the couple of references crop wild relatives as possible sources for solutions:

…hundreds of thousands of older varieties and wild relatives are left to the vagaries of land-use change, global warming and chance. This is a worry because some of the most desirable characteristics of plants—taste, drought- and pest-resistance—originally came from the wild gene pool, which will be needed again one day.

Alas, no mention of genebanks there, you’ll notice. Which I suppose one comes to expect. Didn’t anyone at CIMMYT, IRRI or ILRI — who all get nice name-checks — mention to the writer that in fact hundreds of thousands of samples of landraces and wild relatives are (relatively) safe in genebanks, not least in those very institutes? And that these genebanks need support, and should not be taken for granted?

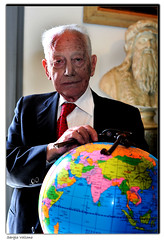

Italian pioneer of agrobiodiversity conservation dies

One of the Grand Old Men of plant genetic resources conservation, Professor Gian-Tommaso Scarascia-Mugnozza, died today at Viterbo. It is perhaps indicative of his stature and influence that there is a Scarascia Mugnozza Community Genetic Resource Centre at the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, in Chennai (Madras), India. He was 85.