- How to breed potatoes, Basque style.

Barley mutants take over world

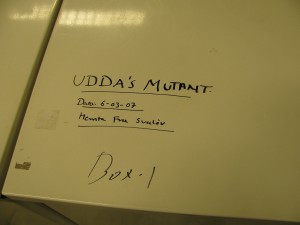

Sometimes nature needs a little help. That was brought home to me in emphatic fashion last week as I listened to the formidable Udda Lundqvist summarize her more than half a century making and studying barley mutants. Some 10,000 barley mutants are conserved at NordGen. In this freezer, in fact:

And Udda described some of the main ones during her talk. You can see some of them, and read all about this work, in her 1992 thesis.

Useful mutations in barley include a wide range of economically important characters: disease resistance, low- and high-temperature tolerance, photo- and thermo-period adaptation, earliness, grain weight and -size, protein content, improved amino acid composition, good brewing properties, and improved straw morphology and anatomy in relation to superior lodging resistance.

Some of these have found their way into commercial varieties.

Through the joint work with several Swedish barley breeders (A. Hagberg, G. Persson, K. Wiklund) and other scientists at Svalöf, a rather large number of mutant varieties of two-row barley were registered as originals and commercially released (Gustafsson, 1969; Gustafsson et al., 1971). Some of them have been of distinct importance to Swedish barley cultivation. Two of these varieties, ‘Pallas’, a strawstiff, lodging resistant and high-yielding erectoides mutant, and ‘Mari’, an extremely early, photoperiod insensitive mutant barley, were produced directly by X-irradiation.

Udda is in her 80s but shows little sign of slowing down.

Purple pride

Purple sweet potato fries? Riiiiiiiiiiiiight. Anyway, let Ted Carey try to convince you.

“The CIP breeder sent me about 2000 seeds from crosses between purple parent plants that looked promising for regions like ours. In 2007, we planted those seeds at K-State’s John C. Pair Horticulture Center near Wichita. Each seed had the potential to be a unique new variety.”

Who says genebanks aren’t used?

When diversity is A Bad Thing

We generally adopt the view that diversity is a good thing. But there are cases where it definitely is not. One such is being discussed over at Small Things Considered, “the microbe blog”. In part one, Elio Schaechter answers Five Questions about Oomycetes. Number one: What makes oomycetes important to people? Answer, potato blight, and many other diseases.

Lots of good stuff, but we’re particularly taken with his colleague Merry Youle’s addition on Oomycete mating types and the potato blight. The point is, late blight is now capable of sex outside its home in Mexico, and has been since the late 1970s. Two consequences follow. First, the spores of sexual reproduction are capable of surviving over winter; currently, cold winters destroy the asexual spores giving potato growers a fighting chance of avoiding the blight. Over-wintering spores could be a disaster. Secondly, and perhaps more important in the long term, sexual recombination will allow late blight to do its own gene shuffling, and could come up with new combinations of genetic diversity that could make it even more virulent. Fungicide resistance in over-wintering spores would be quite a threat. Youle concludes:

K. V. Raman, a professor of plant breeding at Cornell University and an authority on potatoes in Mexico and Eastern Europe, observes: The conditions prevalent in today’s Russia are all too reminiscent of those of Ireland in the mid-19th century. That was the time of the Great Famine in Ireland (the subject of our next post). As was the case then in Ireland, Russia today has a population dependent on the potato and an aggressive blight out of control. In this, Russia is not alone. This time, the impacts are expected to be global.

Scary, or what? I’m looking forward to two more posts promised on the subject.