Jacob kindly suggested I nibble the world’s hottest chilli, but I’m no sucker. I’ll give it the full treatment.

The Economist has devoted a long article to what it cutely calls Global Warming, exploring Why the world has taken to chilies. This is something I’ve had a long-term interest in, as good an excuse to ramble as any.

First off, Luigi’s nibble last year of the World’s Hottest Chile was clearly no such thing, as even then Michael Michaud had made the selection that was to become Dorset Naga. 1 That said, to my inexpert eye Dorset Naga and Bhut Jolokia do look very similar. Any chance of a DNA read-out?

Secondly, Michael Michaud is an all around good egg, and I hope he is profiting from his crazy hot chili. He and Joy, at South Devon Chilli Farm, have been unfailingly generous with their time, expertise and encouragement, and not just to me.

Then there’s the whole question of why people willingly subject themselves to the pain of hot chillies. 2 Long ago and far away, 3 best beloved, I made a television documentary called Why dogs don’t like chilli but some like it hot, which explored this very question. We spoke at length with Paul Rozin, who has studied the topic, and much else about food and taste, in depth and who has concluded that what may begin as thrill-seeking show-off behaviour becomes not quite an addiction, but certainly a craving.

Which, surprise, surprise, is exactly what The Economist concludes, more than 20 years on.

[P]ain relief. The bloodstream floods with endorphins—the closest thing to morphine that the body produces. The result is a high. And the more capsaicin you ingest, the bigger and better it gets.

…

In the same way as young people may come to like alcohol, tobacco and coffee (all of which initially taste nasty, but deliver a pleasurable chemical kick), chili-eating normally starts off as a social habit, bolstered by what Mr Rozin calls “benign masochism”: doing something painful and seemingly dangerous, in the knowledge that it won’t do any permanent harm. The adrenalin kick plus the natural opiates form an unbeatable combination for thrill-seekers.

At least that much is unchanged, unlike the holder of the World’s Hottest Chili.

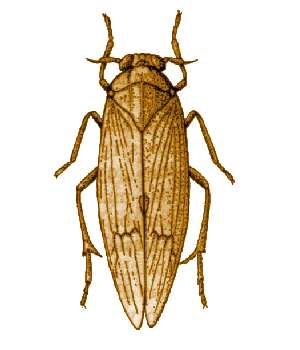

Spraying is what many farmers do, to the detriment of their health and environment. It also makes the pest problem worse. Why? Because pesticides also kill the pests’ natural enemies, such as spiders. So you need to spray again, and again. Until the pests are pesticide resistant. This has led to huge outbreaks of brown plant hopper, like in Indonesia in the 1980s, which only stopped after most pesticides were banned.

Spraying is what many farmers do, to the detriment of their health and environment. It also makes the pest problem worse. Why? Because pesticides also kill the pests’ natural enemies, such as spiders. So you need to spray again, and again. Until the pests are pesticide resistant. This has led to huge outbreaks of brown plant hopper, like in Indonesia in the 1980s, which only stopped after most pesticides were banned.