- Genetic structure within the Mesoamerican gene pool of wild Phaseolus lunatus (Fabaceae) from Mexico as revealed by microsatellite markers: Implications for conservation and the domestication of the species. Three, not just two, genepools.

- Farmer’s Knowledge on Selection and Conservation of Cassava (Manihot esculanta) Genetic Resources in Tanzania. Farmers exchange landraces, some of which are widespread and others more restricted in distribution. Only about 10% are new, but some have been lost.

- Urban cultivation in allotments maintains soil qualities adversely affected by conventional agriculture. You can farm in cities without killing the soil.

- Social institutional dynamics of seed system reliability: the case of oil palm in Benin. Farmers are being increasingly screwed.

- Natural occurrence of mixploid ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) in China and its morphological variations. About a quarter of plants have both diploid and tetraploid cells, and they look different; no plants are wholly tetraploid. Weird.

- Conserving biodiversity through certification of tropical agroforestry crops at local and landscape scales. Certifying the coffee or cacao farm only is usually not enough.

- Is gene flow the most important evolutionary force in plants? May well be, which means that conservationists, among others, need to take it into account. Fortunately, they have the data-rich genomic tools to do so.

- Greater Sensitivity to Drought Accompanies Maize Yield Increase in the U.S. Midwest. It’s agronomy’s fault.

- Desiccation and storage studies on three cultivars of Arabica coffee. Yeah, not orthodox. Didn’t we know that already though?

- Seed-borne fungi on genebank-stored cruciferous seeds from Japan. There’s lots of them. And something needs to be done about it.

- Delivering drought tolerance to those who need it; from genetic resource to cultivar. In making synthetic wheat, you can fiddle with the AB as well as the D genomes, but then you have to phenotype properly under target stress conditions, and have a way of tailoring the resulting global public goods to local needs.

- The Effects of Agricultural Technological Progress on Deforestation: What Do We Really Know? Not as much as we thought we did.

- Large-scale trade-off between agricultural intensification and crop pollination services. Intensification bad for pollinators in France, so bad for agricultural productivity and stability.

- Achieving production and conservation simultaneously in tropical agricultural landscapes. Intensification good for smallholder income in Uganda, bad for birds. If only birds were pollinators.

Brainfood: Ethiopian coffee, Kenyan climate change, Biofortification, Pasture legume adoption, Moroccan veggies, Economics of pests, Grassland diversity & fire, Seed storage, Resistant beans, Maize OPVs, Low P tolerance in NERICA, Brazilian beans

- Prospects for forest-based ecosystem services in forest-coffee mosaics as forest loss continues in southwestern Ethiopia. Coffee agroforests provide about half to two thirds of the ecosystem services of plain old forests.

- Social Process of Adaptation to Environmental Changes: How Eastern African Societies Intervene between Crops and Climate. Your seeds may not be able to cut it in the future.

- Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and provitamin A carotenoids in biofortified staple crops. Focus on breeding varieties with elevated micronutrient concentrations is justified. Phew.

- The future of warm-season, tropical and subtropical forage legumes in sustainable pastures and rangelands. Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. And the past, in this case, was full of mistakes.

- Wild leafy vegetable use and knowledge across multiple sites in Morocco: a case study for transmission of local knowledge? The Rif Mts are a hotspot of weed diversity. Not that kind of weed, settle down. No, wait…

- Agricultural Trade, Biodiversity Effects and Food Price Volatility. Pests are damaging to neat economic models. Pesticides fix that but damage the environment. No word on the economics of natural enemies, integrated pest management, varietal diversity etc.

- Annual burning drives plant communities in remnant grassland ecological networks in an afforested landscape. In the southern Afromontane region, annual burning does not reduce the species diversity of grassland patches, but does make these patches look more and more alike. Add heavy cattle grazing though and that does reduce diversity.

- Responses to fire differ between South African and North American grassland communities. Decreasing fire frequency increased species diversity in Kansas, decreased it in Kwa-Zulu Natal. It’s because of the rhizomatous species in America. What does this and above mean for crop wild relatives?

- Prolonging the longevity of ex situ conserved seeds by storage under anoxia. Remove oxygen to make seeds last longer in genebanks.

- Identification of Sources of Bacterial Wilt Resistance in Common Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Only 1 resistant accession out of 500 in the USDA collection. And it’s a wild one.

- Evaluation of Evolution and Diversity of Maize Open-Pollinated Varieties Cultivated under Contrasted Environmental and Farmers’ Selection Pressures: A Phenotypical Approach. OPVs are diverse and change over time. Still no cure for cancer.

- A novel allele of the P-starvation tolerance gene OsPSTOL1 from African rice (Oryza glaberrima Steud) and its distribution in the genus Oryza. Kasalath comes to the rescue of NERICA. Must be the only sativa gene NOT in NERICA.

- Agronomic potential of genebank landrace elite accessions for common bean genetic breeding. Yeah, but are they in the Brazilian genebank? Doesn’t look like it.

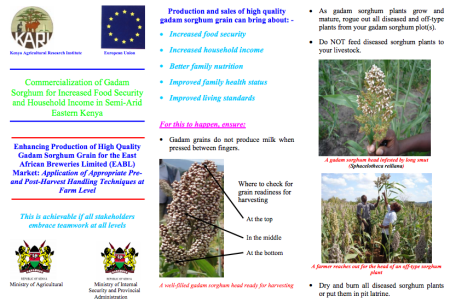

More Gadam lessons

I think that post on Kenya’s beer-brewing Gadam sorghum could do with a follow-up. Quite apart from the mystery of the origin of the variety, which in any case I’m sure is a mystery only to us sorghum illiterates, there are interesting lessons to be learned from the history of Gadam which could be relevant more generally to that group of crops we sometimes call neglected and underutilized. These are nicely illustrated by a couple of papers I found online while researching the previous post. And, yes, I know that we don’t usually consider sorghum a neglected or underutilized species (NUS); but it does have, in some places, at some times, some of the characteristics more commonly associated with crops like finger millet or quinoa: a bad reputation, chronic underinvestment, no markets, you know the kind of thing.

Anyway, it seems, for a start, that Gadam, along with other modern sorghum varieties, has actually been around for a while in Kenya, but was just not getting adopted. Why? Here’s an excerpt from the first paper, “The Role of the market in addressing climate change in the arid and semi-arid lands of Kenya: the case of Gadam Sorghum” (PDF):

Over the years research institutions including the KARI [Kenya Agricultural Research Institute] and the International Centre for Research in Semi-arid and Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) have been working to produce suitable dryland crops. This has resulted in the development of genetically superior cereal and legume crops in terms of yields, early maturity, drought tolerance or drought escaping and higher water use efficiency. Among the cereals, several varieties of sorghum have been developed and released including KARI Mtama 1, Seredo and Gadam among others but the adoption and utilization of the same has been generally poor. The adoption of a technology is affected by many factors but this paper explores two factors (changing dietary habits and lack of markets) and the efforts made by the Kenya Arid and Semi-Arid Lands Research Programme (KASAL) to overcome them and improve the adoption of Gadam Sorghum.

Markets proved key in the case of Gadam. Kenyans prefer maize to sorghum for food, but Gadam was found to have good beer-making properties.

Although KARI had developed several sorghum varieties over time none of these had been targeted to the brewing industry as the main focus was to provide a higher yielding variety for food. As the varieties produced were targeting semi-arid areas with their associated climatic conditions they had to be early maturing and drought tolerant. In association with EABL [East African Breweries Ltd.] several KARI sorghum varieties were tested and Gadam variety was found suitable for making malt beer. Gadam is a short (Figure 4), early maturing sorghum variety (flowers in about 45-52 days and matures in 85-95 days depending on altitude.) The variety matures earlier than the other sorghum varieties and any of the maize varieties making it an ideal variety for areas receiving low and unreliable rainfall. It has been reported to survive and produce grain with approximately 200 mm of rainfall in Machakos area. The grain is high in starch, low in protein and tannin making it suitable for malting. Gadan grain has 75% carbohydrate compared to 67% in barley and 66% in maize making it a good alternative source of starch. Further analysis showed that Gadam had low levels of oil and proteins which makes it good for industrial processing. Through tests for enzymatic digestion of starch, Gadam was found to have high levels of fermentable sugars.

Once the right variety had been found, a model of smallholder production had to be developed that would allow EABL to abandon its predictable preference for being supplied by large-scale contracted farmers. That was found in a private-public partnership based on commercial production clusters of 20-30 members, each with a collection centre serviced by a private company that did the bulking and shipping to EABL; but with certified seed, training and quality control provided by different government agencies, and micro-finance by various banks.

It seems to have worked. Gadam farmers keep lower quality grain back to eat themselves or feed to chickens (leading to a bit of a poultry industry), and buy maize for food and other stuff with the profits they make from selling the good stuff to EABL. Everybody wins.

So is it all sweetness and light? Another paper, “The potential role of sorghum in enhancing food security in semi-arid eastern Kenya: A review” (PDF), hints at further opportunities:

Due to increased health concerns and awareness, the use of sorghum products has seen a gradual increase as reflected by the quantity and range of processed sorghum products sold in local supermarkets (Kilambya and Witwer, 2013).

But it also notes that increased interest in sorghum by both brewers and the consumer has not yet been matched by public investment in research, breeding and seed production:

The agricultural sector development strategy, 2010-2020 also noted that the decline in productivity of orphaned crops was partly arising from low use of improved seeds due to poor distribution systems and the monopoly of the Kenya seed company which concentrates its operations in high rainfall areas (GoK, 2010). The other major problem facing the sorghum subsector is the dominant position of the single market provided by East African breweries for the Gadam sorghum which is widely grown by farmers in the semi-arid eastern Kenya. Although EABL has helped to address the problem of marketing, it has led to a situation where farmers do not have an alternative market to sell their surplus produce or grains that do not meet the standards set by EABL. Cases of grains below standard have been encountered due to seed impurities especially mixing of varieties common with commercially supplied seed lots (Miano et al., 2010). The other problem facing the sorghum sub-sector is an image problem where it is considered to be a food crop for the poor and vulnerable communities in the ASALs. As such its consumption in the urban areas is extremely low and many urban dwellers prefer maize thus lowering the to expand the market and increase acceptance of sorghum among the more financially endowed middle class residing in urban areas.

So, one could truthfully say that there is now in Kenya renewed interest in a traditional crop, but that would be only part of a much more complex story. There is really only increased interest in one, exotic variety of that crop; we know that local landraces persist alongside Gadam, but for how long? That interest depends on a single commercial company, and could end tomorrow. And although there are encouraging signs of wider public acceptance of some of its benefits, sorghum still has an image problem in the cities.

I mentioned some general lessons for NUS at the top of this piece. What are they? I’d say the main one is the obvious one: diversify your risk. Promote diversity of the crop, rather that just one or two varieties. Preferably by improving local varieties rather than parachuting new stuff in. Make sure the private and public sectors are working together. And don’t rely on a single value chain. Even if it is beer.

Getting down with Gadam sorghum

Kirinyaga County government will this week start distributing free Gadam sorghum seeds to residents of South Ngariama settlement scheme as way of fighting poverty in the area. The exercise which will see the residents receive 2,000 kg of the free seeds is expected to be flagged off by Governor Joseph Ndathi.

Interesting enough, but a month-old Kenya News Agency press release about the distribution of some sorghum seed, even free sorghum seed, wouldn’t normally exercise me unduly. Except, that is, when the above is followed by this:

The Gadam sorghum is best suited for industrial production of beer and farmers are expected to rake thousands of shillings from sale of the produce which will be marketed to the Kenya Breweries Limited (KBL).

Ah, well, now you’re talking. I did know that sorghum is increasingly being used in beer brewing in Kenya, but I didn’t realise that there was a specific variety involved, I thought any old sorghum, including landraces, would do. You can get extension leaflets on Gaudam, such as this:

Which is just as well, because there are clearly some problems with it, as well as undoubted advantages, in particular earliness. The value chain for sorghum beer in Kenya has been well documented, and from that study comes this admittedly sketchy description of the Gadam variety and its history:

Sorghum beer is made from Gadam, a semi-dwarf sorghum variety with specific market traits, including white colour, low tannin and a high starch content. Originating in Sudan, Gadam was officially introduced in Kenya as a food crop in 1972 but then re-launched as an industrial crop in eastern Kenya in 2004. The KARI Seed Unit, located at Katumani, was established to grow and market seed of open-pollinated varieties (OPVs) that were unprofitable for private seed companies. It is the biggest producer of sorghum seed in Kenya. The Seed Unit sub-contracts seed production to 3000 growers who are advanced seed and repay in kind after harvest. The minimum acreage for a contract farmer is five acres. The Seed Unit buys whatever quantity farmers want to sell, provided it passes seed inspection by KEPHIS. Sales are made to large buyers but not to stockists because of risk of adulteration

Gadam is widespread and common enough to have been included as a sort of control in a recent survey of sorghum diversity in Kenya, which includes this passage:

In contrast to the case of some landraces, improved varieties were uniformly distributed and their frequencies did not differ between ethnic groups. The recently introduced Gadam variety was genetically distinct from the landraces and showed limited introgression from the other genetic clusters. It was genetically uniform and complied with certified control. However, farmers also gave the names of local and already known variety to individuals that have the same genetic profile as Gadam, an improved variety. This can be explained by a morphological similarity. Yet it raises the question of the consequences this will have for the on-farm evolution of the improved variety. Kaguru, for instance, which was introduced in the area 10–15 years ago, seems to have evolved differently across ethnic groups.

So Gadam‘s genetic future is uncertain. It may well change significantly, and in different ways in different places, and that will be interesting to follow, though those brewers may perhaps object. But what about its past? Can we trace Gadam back in time to its source? Unfortunately, I was not able to find anything online about its pedigree or breeding history, beyond hints at the involvement of ICRISAT, and vague references to an ultimate origin in Sudan. I’ll have to ask some sorghum experts, I suppose. Or look harder. However, my searches did produce one lead. There are 5 entries in GRIN that feature the word Gadam, including two from Sudan, a 1945 introduction called Gadam El Haman, PI152664, and a much later introduction called Gadam El Hamam, PI571389.

Note the slight difference in the last word of the name — hamaN versus hamaM. I think the first version may perhaps be a typo. I can’t find an Arabic word that can plausibly be transliterated as hamaN; hamaM, on the other hand, may mean “bath,” or perhaps “dove.” Gadam is even trickier, because that initial G could equally be a ق (leading to the noun “foot”, or possibly to a verb which may mean “to present”), or a خ (leading to the verb “to serve”). Bringing my mighty Arabic resources to bear on the problem, I conclude that the full name could well be translated as “footbath.” Or perhaps “serving the dove.” The perils of a little knowledge. Whichever it is (and I can’t for the life of me think why a sorghum variety should be called either), I’m no closer to knowing whether either, or neither, of those PI numbers is the ultimate source of Kenya’s Gadam, tout court. But I’m going there next week. Maybe I’ll ask around. If I find anything, I’ll let you know. And have a sorghum beer in celebration.

Nibbles: Coffee rust, Wheat blast, Livestock yield gap, Livestock adaptation, Extension, Med diet, Organic < conventional, Douglas fir breeding, Best moustache in cryo, Fortifying rice

- Coffee rust is doing a number on livelihoods in Central America.

- Wheat blast could do the same in South America.

- ILRI DG on smallholder livestock producers: one-third don’t have the conditions in which to be viable, one-third can go either way and one–third can be successful. I suppose all of them are going to need adaptation options.

- Not to mention extension services.

- Meanwhile, bureaucrats busy protecting the Mediterranean diet.

- The inevitable productivity penalty of organic.”

- Douglas fir ready for its genomic closeup.

- Cryopreservation update, with video goodness.

- Lots of ways to skin the malnutrition cat: zinc and rice.