A video has just surfaced about the Australian Pastures Genebank, courtesy of the Grains Research and Development Corporation (GRDC), starring my mate Steve Hughes. Here are the headline numbers: 70K accessions, 2K species, collected over 60 years, ROI 119:1. Say what? Return on investment in a genebank of over 100 to 1? How come I’ve never come across this before? Well, it’s from a 2007 report to the Steering Committee of Australia’s National Genetic Resource Centre entitled “Benefit-cost analysis of the proposed National Genetic Resources Centre.” And I can’t find it online. But Steve has promised to send it. Stay tuned…

Nibbles: Wine & CC, Native American food, Olives in Crete & Palestine, Adopt-an-Alpine-Cow, Landscape terms, Gates investments, African smallholder advice

- Grape-ocalypse now.

- Take the Healthy Roots Indigenous Wellness Challenge.

- A Kickstarter to map Crete’s ancient olive trees. And why not? Maybe Palestine next?

- Different sort of crowdfunding for Italian cheese.

- Please, sir, what’s a ujleer.

- Gates Foundation throws Big Fast Food under the bus.

- African smallholders told to diversify. Like they don’t know already.

- African smallholders told to link up with markets. African smallholders tired of getting advice.

Building a European Plant Germplasm System

A couple of days ago we blogged about a study by European genebankers which recommended the establishment of a “European Plant Germplasm System” (EPGS) along the lines of the US National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS). Let’s see how far the analogy can be pushed.

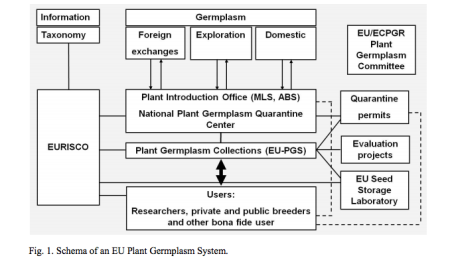

Some of the key features illustrated in the diagram of the “EPGS” provided in the paper, and reproduced in our post, are: active germplasm collections, a central seed storage laboratory, a system-wide information system and a plant germplasm committee. There are some interesting differences between the European and US versions of each of these. The constituent European germplasm collections, for example, would be the national collections, which tend to have a very wide range of species; whereas in the US some at least of the individual germplasm repositories are fairly focused on a crop or group of similar crops. That makes for efficiencies. Or would all the “small grains” in Europe end up in one national genebank, and all the apples in another, as in the US?

Another difference, as we discussed in the previous post, is the nature of that European plant germplasm committee. There is supposed to be only one of these in Europe, whereas in the US there is one per crop, to provide guidance and advice from germplasm users to the crop curator. That to me makes more sense.

As for information systems, Eurisco is not at the moment comparable to GRIN. The NPGS uses GRIN (GRIN-Global in the near future) to both manage workflows within the genebank and make some of the resulting data available for searching on the internet. Eurisco does only the latter at the moment (and, incidentally, like GRIN, serves its data up to Genesys). But then I expect the individual European genebanks are quite happy with their various data management systems and don’t necessarily need to share a single, standardized system. Or do they?

Perhaps the biggest difference, however, is with the central seed storage laboratory. There is at present no European Ft Collins at all to provide safety duplication of seed accessions. It would have to be built from scratch. Or perhaps one of the bigger national genebanks could suck in safety duplicates and morph into a regional genebank? But is a single central repository really necessary at all? What if, instead, you had different national genebanks taking regional responsibility for safety duplication of different crops? This would not be a new idea by any means, though I don’t think it’s ever been implemented anywhere in the world. Might it be an option in Europe?

Then there’s the stuff that’s not on the diagram. Take coordination mechanisms. The NPGS has biennial face-to-face meetings of all genebank curators, with teleconferences in the “off-years.” Plus there’s national–level coordination by the ARS Office of National Programs. The National Plant Germplasm Coordinating Committee coordinates and communicates information among federal, state and other funding entities. A related issue is administrative structure. NPGS genebanks are budgeted in a ARS Research Project, which is funded by an annual Congressional appropriation. This in turn contributes to ARS National Program 301 (Plant Genetic Resources, Genomes, and Genetic Improvement). Every five years, each National Program and its constituent Research Projects undergo external reviews. After that, each Research Project writes a new Project Plan for the next five years for review. What would European coordination and administration on crop genetic resources look like? Some is already provided by the European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Resources (ECPGR), of course. Would ECPGR’s processes and structures — not to mention funding — be sufficient for a European Plant Germplasm System?

So. I guess the bottom line is that it’s easy to say that it would be nice to have a European version of the US National Plant Germplasm System. But then you start to drill down into what that would actually mean, and lots of options open up at each turn. And, at each turn, whether it makes sense to do it in Europe exactly like they do it in the US will, as they say, depend.

What does it cost to conserve crop diversity in Europe?

There’s a document on the NordGen website entitled Towards a European Plant Germplasm System — The third way 1 which advocates setting up a “European Plant Germplasm System” along the lines of the US National Plant Germplasm System. Written by Lothar Frese, Anna Palmé, Lorenz Bülow and Chris Kik — all from big European genebanks — the paper “builds on the results of the PGR Secure project funded under the EU Seventh Framework Programme.”

This is what the European system would look like:

What, no Svalbard? Even the NPGS uses that. Also, there are separate germplasm committees for each crop in the US, rather than one committee to rule them all. That makes more sense if the idea is to have input from the users, as in the US; but maybe that’s not it, as in the diagram the committee is not linked to the users. So what is it for? Anyway, how much would this all cost?

As a rule of thumb, the ex situ conservation including related research costs approximately 60 € / accession and year (personal communication of Dr. U. Lohwasser of 23 May, 2014 and Dr. P. Bretting of 22 May 2014). 1,725,315 accessions are kept in European genebanks resulting in an assumed total annual costs for ex situ conservation of 103,518,900 € per year for the whole of Europe. In view of the 34 billion € spent for agri-environmental measures within the EU-28 a budget of 100 million € / year is not unreasonable. The question rather is whether the stakeholder groups and policy makers feel that having a European Plant Germplasm System is worth this amount.

Well, let’s fact-check that. The operating budget for the NPGS is $44,600,000 per year, for 569,000 accessions, which is about $78 per accession, or about €70 at today’s exchange rate. That’s probably a conservative estimate, I’m reliably informed, as the NPGS gets a lot of in-kind support from the universities with which it cooperates — but it’s the right ballpark anyway. The international genebanks of the CGIAR get around $20 million a year to maintain and make available their ca. 700,000 accessions, which seems very cheap, but includes very little of those “related research costs.”

What we don’t know — or at least I don’t — is what European countries are actually spending on their genebanks at the moment. It seems maybe the authors don’t know either, because another of the 12 recommendations they make, besides establishing the system, is to inventory the money available. Here are all the recommendations, conveniently filleted out for you. Look at number 6:

1. We suggest the establishment of a European Plant Germplasm System.

2. Establish a legal basis for conservation of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture in the EU.

3. Establishment of a technical EU infrastructure for the organisation of conservation of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture measures.

4. Establishment of an EU information infrastructure for conservation of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture.

5. Disentangle juridically and financially genebank tasks from plant breeding research and plant breeding tasks at the national level.

6. Inventory of financial means available to genebanks and estimation of financial means needed for a fully functioning European network of genetic resource collections (ex situ, in situ and on-farm).

7. Increase the visibility of plant genetic resources collections on the internet.

8. Develop a European platform for long-term crop specific pre-breeding programmes.

9. Clear uncertainties concerning Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) rules so that breeding companies can take economic decisions on a safe legal basis.

10. Research should be strengthened to better understand the amount and geographic distribution of genetic diversity present in priority crop gene pools.

11. The European agro-NGOs and their influence should be strengthened.

12. Establishment of a European Network of Private-Public-Partnership programmes for evaluation of plant genetic resources in Europe.

My own recommendation would be to start with that inventory of financial means. It would be nice to know how close to that €100 million we in fact are — and how much of it, if any, would need to be new money.

Nibbles: Biltong, Coco de mer, PGRFA course, Poplar genebank, IRRI genebank, African agriculture, Hybrid chickens, American food

- Professor wants to copyright the name biltong, should be forced to eat nothing else until he takes it back.

- Getting to the bottom of coco de mer.

- PGRFA course at Wageningen. Expensive, but worth it, and you can apply for a NFP/MENA Fellowship, check on the course overview PDF.

- The IRRI genebank manager has seen the future of genebanks: “…we need to work on building the system to estimate breeding value from genotype, and then we will be able to feed more detailed knowledge to the breeders.” He probably means DivSeek. Now IRRI really need to get a different stock image of him and his genebank.

- The UK now has a National Black Poplar Clone Bank. Not quite as big as the above.

- A different take on Bill’s Big Bet. And more along the same lines.

- Hybrid Kuroiler chickens a big hit in Uganda. Bill may be onto something after all.

- “As American as apple pie” is just the beginning. I want to see Kuroilers at KFC.